The Irish in Atlantic Canada represent a community of considerable size. Many Irish spent years in Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island or New Brunswick before eventually migrating southwards to communities in Boston, Maine or elsewhere.

The Irish in Atlantic Canada represent a community of considerable size. Many Irish spent years in Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island or New Brunswick before eventually migrating southwards to communities in Boston, Maine or elsewhere.

During the eighteenth century many Irish came to Atlantic Canada as migratory fishermen and laborers recruited by English ship captains stopping into Waterford and Cork for provisions on the way to the Newfoundland cod fisheries. By the beginning of the nineteenth century with Ireland suffering from the effects of a population explosion, progressively greater crop failures and oppressive penal laws, its increasingly poor citizens continued the exodus. Acting as human ballast they travelled in the holds of brigs which would make the return journey to Britain laden with timber from the Miramichi.

The Irish began to arrive in Nova Scotia from 1747 onwards–most of them were known as “two boaters” — those who originally arrived in Newfoundland but later traveled on in search of a better life. By 1836 one third of the residents of Halifax city had been born in Ireland. Many of those early settlers now lie side by side in their thousands in Holy Cross Cemetery with no one to acknowledge their presence but the crows in the graveyard calling out continuously.

Today, census figures tell us that 14 percent of the population of Nova Scotia can trace their ancestry back to Ireland. Their numbers are likely to be underestimated since the Irish tend to intermarry with the Scots and the English.

Just over one hour drive north of Halifax is a bustling town called Truro. Sixty New England Presbyterian families originally from Ulster settled here between the years 1760 and 1762 under the leadership of Alexander McNutt. Scattered through the graveyards of Truro and outlying villages such as Onslow and Londonderry, the Archibalds, Millers, Aikens and McMullen are just some of the Northern Irish names to be found.

Substantial numbers of Irish also settled in the fishing communities of Guysborough, Arichat and St. Peters all lying in the southeast of Nova Scotia. Many of those arriving in St. Peters between 1780 and 1830 were encouraged to come by a wealthy Irish merchant called Lawrence Kavanagh. In Arichat, you will find amongst the families of French heritage prevalent there, quite a few fishing families of Irish descent. Sweeneys from Cork, Hennnessys from Kilkenny, and Flynns from Durgavan are just a few of the immigrant names on the grave stones overlooking the picturesque inlet at Aricaht. These beautiful isolated communities are not unlike their seaboard counterparts in Ireland.

St. John, New Brunswick

Over two thousand Famine Irish got no further than a mass grave on Partridge Island, a quarantine station which lies in the harbor of St. John, New Brunswick, a two and half hour ferry ride from Nova Scotia. Destitute, they fell prey to typhus, dysentery and other infectious diseases.

The Irish, primarily from Cork and western Ulster, constituted 35 percent of the St. John population in 1871 but by 1941 that figure had slipped to 20 percent. From the census figures and shipping records it is obvious that, in time, many moved on to the United States.

The bigotry suffered by the Catholic Irish in St. John echoes that of other Irish settlements throughout the Maritimes. In modern day st. John the bigotry has dissipated yet the bitterness remains with some that suffered growing up in those Irish enclaves.

Prince Edward Island is another interesting piece in the puzzle that makes up Irish Atlantic Canada. Traditionally the Irish in Prince Edward Island were known as Famine Irish; however, the overwhelming number of Irish arrived on the island before the Famine. They were for the most part poor, originally coming from the Waterford area but later on primarily from Monaghan. Charlottetown became known as Irishtown for a time but like other two-boaters, many of these Irish moved on and in time the Irish representation of the population was to drop to 20 percent. Today abundant family names, place names and folk songs still indicate the sizable influence the Irish have had on Prince Edward Island.

Newfoundland

An hour and a half from Nova Scotia and two centuries removed from Ireland, parts of Newfoundland at times seen caught in a twilight z

one between the two cultures. Named “Talamh an Iasc” (Land of the Fish) by the Irish, Newfoundland is a wild a beautiful outpost of North America with summers not unlike what the migrant fishermen must have experienced in their native home. A sizeable 36 percent of Newfoundlanders are of Irish descent. Prior to 1836, thirty five thousand Irish had landed in Newfoundland. Originating primarily from Ireland’s southeast due to port links with Waterford, many were to become two-boaters travelling first to other destinations in Atlantic Canada and often on to the United States. By the end of the eighteenth century the Irish population had settled predominantly in the most easterly part of the island called the Avalon Peninsula. Today, not surprisingly, the most vibrant remnants of Irish culture in all of Canada are to be found on the Avalon Peninsula. Linguistic specialists have discerned the accent in many parts as Waterford in origin. Driving along the coastline south from St. Johns you will see nothing but a seamless presence of Newfoundland Irish, store fronts and street signs invariably with Irish names. Further along the Southern Shore you will spot the odd stone awall and other small farm characteristics reminiscent of parts of rural Ireland.

Until the 1820s the dominant language of the peninsula was Irish not English. Philip Henry Grosse the naturalist said of Newfoundland: “I see little in it but dogs and Irishmen.”

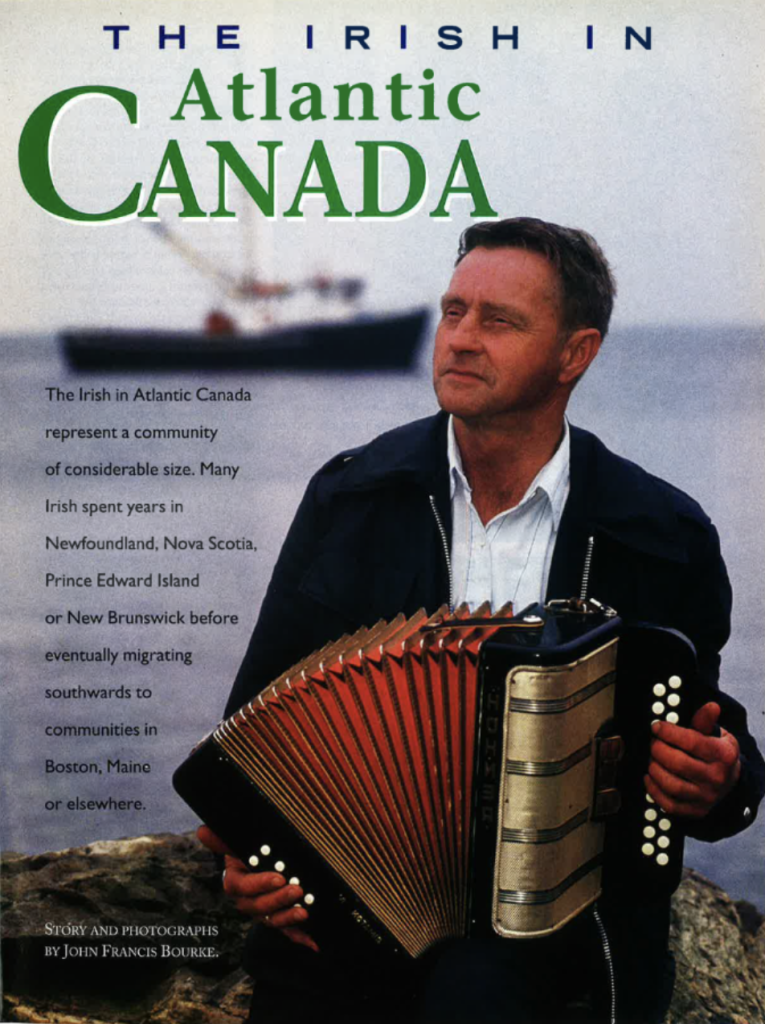

A province once divided along religious lines, the bigotry has all but disappeared. The local people, their livelihoods suffering from a moratorium on cod fishing, are more concerned with eking out a living on the bays and inlets of Newfoundland. The Dunnes of Renews is one such family in whose kitchen I spent several hours in endless conversation punctuated with accordion music and dancing. Though not particularly knowledgeable about their Irish background, their speech rhythms and words are remarkable in how little the Irish accent of that community has changed in two hundreds years. Over Moose stew in the home of Doug Dunne, I learned that a visit from the Wren Boys on St. Stephen’s day (a uniquely Irish tradition on December 26) is not uncommon. A visit from the Mummers an ancient folk tradition practiced in both Wexford and the West of England is also found but is less common.

Further down the coast I spent a day with the family of Mike Dobbin, a man who looks and sounds like he walked straight off the pages of a Frank O’Connor short story. We travelled out by boat to enjoy a traditional “Jiggs Dinner” with music and song on a now deserted island where Mike grew up. His idle trawler is a constant reminder to him of how the dwindling fish catches and the subsequent ban has left him with nothing but time to reflect back on the decades he spent at sea. Of the many storries Mike tells, my favorite one is how while out on a small boat checking his nets he found a whale barely alive tangled up in one. Exhausted and now quiet from its fruitless struggle, Mike and his men slowly approached the whale knowing that any movement by it would be sufficient to turn the boat over. Carefully Mike and the crew cut through his valuable nets to eventually free the animal. The whale, turning around momentarily to acknowledge the boatmen before swimming away is one of many accounts I heard which validated my belief that these ocean people have a spiritual connection to their environment.

Close to where the Dobbins live is a little village called St. Brides. Notwithstanding the fact that its cottages are made of wood rather than stone it has the haunting stamp of an Irish way of life unchanged for decades. With its brightly colored little homes appearing then disappearing through the rolling fog, I fancied I could almost hear the steady footfalls of our Irish forefathers and mothers stepping quietly down the road.

The writer would like to thank the Irish Canadian academic community whose extensive work on Irish emigration and culture in Atlantic Canada was an essential resource for this article. In addition the writer would like to thank the people of Atlantic Canada for their generosity and kindness.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the July/August 1995 issue of Irish America. ♦

Leave a Reply