The name Grosse Ile (Big Island) is almost a generic term on the map of North America, it appears in so many places. But there is one island by that name that far outstrips the others for the drama and pathos that took place on its shores.

Grosse Ile in the Saint Lawrence River near Quebec City is the spot sometimes called “The Island Graveyard,” or “L’Ile des Irlandais” (The Isle of the Irish), its tragic reputation comes from the awful scenes of 1847 when those seeking refuge from the Irish famine landed on its shores.

Grosse Ile was chosen as a quarantine station for the colony of Canada in 1832, when the imperial government became alarmed by the cholera epidemic then sweeping Europe. There was debate over whether the disease could cross the ocean or not. Ship owners could not be persuaded to reduce the lucrative “immigrant trade.” so the best the government could do was provide a place where the sick immigrants might be cared for.

The site chosen for the quarantine, Grosse Ile, was a pretty little island about a mile and a half in length and a mile in width. It stood in an anchorage with a good clay bottom, was sheltered by other islands, and there was room for up to a hundred vessels. As it lay thirty miles below Quebec City the principal port on the Saint Lawrence at that time, it was felt that it could serve as a barrier to prevent the entry of any diseases into Canada.

In the spring of 1832, the military authorities set about in fairly leisurely fashion to prepare living quarters for medical and military staff, to build a hospital, a cook house, and all the other amenities the island needed. Before it was completely ready, however, the first ships arrived, early in May with dreaded cholera already among the passengers. In fact, the first victim succumbed in a boarding house in Quebec City his ship having gotten through the quarantine with cholera undetected by the inexperienced medical men. The island was soon overwhelmed, its facilities strained beyond imagination.

Ships were allowed to proceed to Quebec since the island could not care for them, and cholera spread throughout the colony, as far west as Toronto. So much for its baptism of fire, but worse was to come within a brief fifteen years. Instead of trying to improve the effectiveness of the quarantine center, the work at the station slowed down. Due to the epidemic of 1832, fewer immigrants seemed to dare the crossing in 1833 and 1834, and consequently, a spirit of laissez-faire descended on the works of the island. This sluggishness resulted in a haphazard approach to the maintenance of the quarantine and the ensuing lack of preparedness for another onslaught.

Overseas, in the meantime, during the early part of the century, little change occurred in living conditions for the poor in Ireland, Scotland, and England, and immigration to Canada continued as a solution to the poverty and lack of liberty at home. Three factors must be kept in mind: first, the timber trade between Britain and Canada had resulted in a system of ships carrying timber from Quebec City to Liverpool and other British ports, never returning empty.

Ship owners discovered early that people would pay to go to North America even in the almost bare hulls of the timber ships; second: only ships of British registry were allowed entry into the Saint Lawrence during this pre-free- trade period; third: passenger fares were cheaper from Great Britain to Canada than from Great Britain to the United States, and there were no anti-immigration laws in Canada. These three conditions explain the fact that for the first half of the nineteenth century Canada’s immigrants were all from the British Isles and Ireland, and the majority of immigrants every year were Irish.

For many, Canada was a stepping stone to the United States. British government miss-administration, the injustice of the land-owning system, and the cold aloofness of economic powers indifferent to human suffering were bound to culminate at some point in a tragedy of massive proportions. That calamity struck Ireland and affected Canada, and indeed, the United States, 1847 when the potato crop in Ireland failed in the mid-1840s, the efforts made to alleviate the hunger through the Poor Laws, the poor houses, and the public works programs, were half-measured, and little more than band-aids applied to wounds festering from centuries of harsh misrule.

Before opting for these solutions, many landlords offered emigration incentives to their tenants: free or cheap passage to America, promises of clothing, food, and shelter once there. There was much deception, later recounted with sadness and dutifully recorded by the authorities in Canada. On the other hand, there is also evidence of compassion on the part of some landowners and ship captains but unfortunately, these occurrences were so rare as to be almost phenomena. In British government circles, it was soon found that there was no need to offer incentives to emigrate, as Lord Grey of the Colonial Office wrote as early as 1846: “some £150,000 would have to be spent in doing that which if we do not interfere will be done for nothing.”

The people were going to go, anyway, and the means had already been established, the ships of the timber trade. Now the ship owner and the ship captains conspired to open wider the avenue of escape: besides the regular timber ships crossing the Atlantic, old ships, barely sea-worthy were called into service and “fitted” for the immigrant trade. “Fitting” often meant little more than nailing rough planks together to form sleeping platforms and crude tables for the passengers. The proliferation of Navigation Laws intended to prevent overcrowding and other bad conditions on the ships underlines the scoff-law approach of many shippers to the care and well-being of their passengers. The “coffin ships” got their name at this period in history.

Eighteen forty-seven stands out as the worst of the famine years. The previous year’s crop of potatoes rotted in storage, and people simply fled if they could. Once onboard the ship, those suffering from malnutrition fell easy prey to typhus, or ship’s fever, carried by lice, easily transmitted from person to person-given the close quarters, and lack of washing facilities on board. Thousands of Irish died at sea, and were buried there, sent off from the ship’s side. Here is part of a newspaper description of the ocean voyage: “The crossing takes 36 to 80 days. The passengers are herded into small crafts, usually 250 to 500 per boat. There are some provisions that are issued once a week, like oatmeal, cooked by the passengers in a little galley at the waist of the ship. Sleeping quarters are in the low, dark steerage between decks and midship. Ventilation is furnished by a windsail at each hatch. Sanitation, if any is of the slop jar variety.

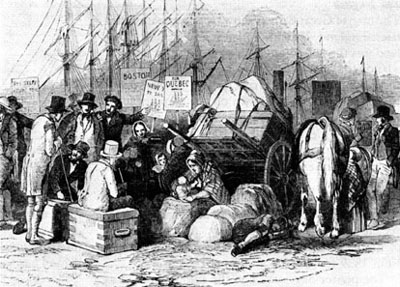

At Grosse Ile, the doctors soon realized with horror that they could not cope with the thousands being dumped on their beaches. Personal misery was compounded by the lack even of such elementary physical features as a dock or pier on which passengers could come ashore. Until the end of the summer of 1847 people had to clamber down steps or ladders off the ships onto lighters, or rowboats, to be brought ashore. Graphic are the scenes: old and young, pale and feeble, men, women and children, the healthy and the sick, trying not to lose each other, trying to hold onto their possessions, scrambling awkwardly down the steps or the ropes.

Passengers sometimes panicked and upset the small boats, manned by inexperienced soldiers who knew not how to stabilize the tipsy little vessels. Worse still were the times, many of them, when not one person, crew included, could take a single step off the floating charnel house that had come to rest at last. Aubrey de Vere depicts the emptying of a ship of its passengers by winching the corpses out of the hold. Heart-wrenching is his description of a beautiful little girl with long blonde hair wafted by a breeze as her body was hoisted into the air, to be piled among the other corpses on a barge.

The reports from Grosse Ile also stressed the great numbers of children being landed. The story of the care of these children is one of the most touching in Canada’s history. Some historians estimate that there were fifty children for every adult and any one of the child survivors of the time could have told a story similar to that repeated to this author by Leo Tye of Ste. Croix de Lotbiniere in Quebec. Leo’s grandfather, Daniel Tighe, twelve years of age, and his sister Catherine, nine, left Lissinoufy in County Roscommon with their mother, and arrived at Grosse Ile aboard the “Naomi,” in August of 1847 Mary Kelly widow of Bernard Tighe, had accepted “assisted immigration” from the Roscommon estates and hoped the best for herself and her children. When she died at Grosse Ile, the children, like hundreds of others, were cared for by the priests who had come to minister to the dying. These priests, both Catholic and Anglican, brought the plight of the orphans home to their parishes, and it is there, in the heartland of Quebec, that the glorious drama of welcome ensued.

Throughout the summer of 1847, gentle traffic took place: the priests, going off duty would gather a group of children about them, and ferry them to Quebec City where they were placed for immediate medical care in an orphanage started by a group of French, Irish, and English women, Protestants and Catholics. The priests then spoke to their parishioners on the following Sunday and returned to the Quebec City orphanage to collect the children for whom they had homes. In Daniel Tighe’s case, the adoptive parents were an older couple, Francois Coulombe and his wife, who wanted a boy who could help with farm chores. When they indicated that they would take Daniel, and not his sister, the two children began to cry in each other’s arms. One can picture the old couple shrugging and saying, “We’ll take both,” which they did.

The childless Francois and his wife willed their land to the adoptive son, and today great-grandchildren and their children, live there, bearing the name lye, easier to spell and pronounce, speaking French as their only language, very conscious of the heritage of Ireland in their veins, and of French Canada’s welcome.

It was not only French families, however, who took in the orphans. Many Irish had been established in Quebec City and in villages of the hinterland for forty years and more, and the predicament of their fellows at Grosse Ile was not lost on them. There were many Irish families, as one might expect, who adopted orphans during that summer of sorrow.

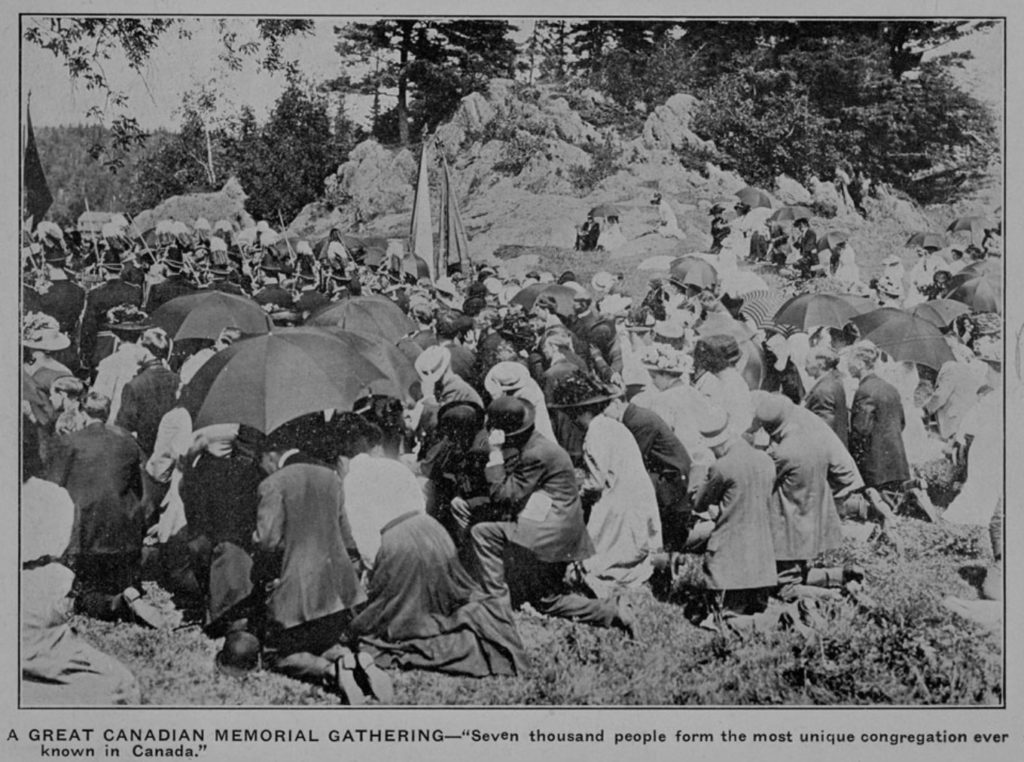

In 1897 fifty years after the worst year of the Famine, a group of Quebec City members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, went down to Grosse Ile to visit the place. Great was their distress when they saw the woeful condition of the abandoned cemetery and realized that there was not a single marker to commemorate the fact that thousands and possibly tens of thousands of Irish had been buried there in 1847.

By 1909 the Order had collected enough money in both Canada and the United States to enable them to unveil a magnificent forty-foot granite Celtic Cross on the highest point of the island. The inscription reads, in part: “Sacred to the memory of thousands of Irish Emigrants who ended here their sorrowful pilgrimage. Thousands of the children of the Gael were lost on this island while fleeing from tyrannical laws and an artificial famine, in the year 1847.”

A noted journalist of the time described the erection of the memorial thus: “Peace has its victories but it also has its tragedies. The huge Celtic Cross that majestically raises itself on high from its island foundation will serve to remind us that there are nobler heroes found in lowly places than in the dramatic din of the battlefield. It will serve to make known the heroic dedication of those brave people who risked their lives in coming to the rescue of these poor victims of a man-made calamity.”

When next you come to the Province of Quebec, reserve a day for a trip to this extraordinary island now being developed as the newest in Canada’s National Park System

Editor’s Note:

The Irish currently makes up the fourth largest ethnic group in Canada, with almost four and a half million Canadians claiming either full or partial Irish heritage. The majority of Irish immigration to Canada took place in the wake of An Gorta Mór, in the mid-nineteenth century. All the “Coffin Ships” that brought Irish emigrants the three thousand miles to Canada had to stop at Grosse Ile, the quarantine island where ships waited to port as the Canadian government was concerned about the diseases that ravaged the vessels. While the number of deaths at sea and burials at Grosse Ile is vast, and the young ages of many of the victims are heartbreaking, the presence of marriage and baptism records make tangible the sense of hope that immigrants and their descendants felt upon their arrival in North America. The excerpts below are just a small portion of the Library and Archives Canada and Parcs Canada’s database of 33,026 immigrants whose names appear in surviving records of the Grosse Ile Quarantine Station between 1832 and 1937.

Deaths at Sea 1847

| Name | Age | Date of Death | Ship | Port of Departure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson, Jane | 60 | 1847 | Christiana | Londonderry |

| Armstrong, Ann | 4 | 1847 | Christiana | Londonderry |

| Bailey, Eliza | 3 | June 6, 1847 | Christiana | Londonderry |

| Blakely, William | 1 | June 5, 1847 | Christiana | Londonderry |

| Blakely, Francis | 16 | 1847 | Christiana | Londonderry |

| Campbell, James | 3 | June 5, 1847 | Christiana | Londonderry |

| Campbell, John | 40 | 1847 | Christiana | Londonderry |

| Coyle, George | 3 | June 1, 1847 | Christiana | Londonderry |

| Coyle, Robert | 12 | May 27, 1847 | Christiana | Londonderry |

| Doherty, Ann | 1 | 1847 | New York Packet | Liverpool |

| Doherty, Patrick | 18 | 1847 | Sisters | Liverpool |

| Doherty, Sarah | 35 | 1847 | Christiana | Liverpool |

| Fitzpatrick, Bridget | 50 | 1847 | Christiana | Londonderry |

| Fitzpatrick, Dennis | 2 | 1847 | Minerva | Galway |

| Fitzpatrick, Eliza | 14 | 1847 | Progress | New Ross |

| Gallagher, Peter | 1 | 1847 | Christiana | Londonderry |

| Harty, Thomas | 4 | 1847 | Lord Ashburton | Liverpool |

| Kelly, Bridget | 50 | 1847 | Avon | Cork |

| Kelly, Mary | 32 | 1847 | Christiana | Londonderry |

| Kyle, Eliza | 8 | 1847 | Christiana | Londonderry |

| Kyle, Joseph | 1 | 1847 | Christiana | Londonderry |

| Kyle, Robert | 13 | 1847 | Christiana | Londonderry |

| Kyne, Christiana | 8 | 1847 | Christiana | Londonderry |

| Leslie, James | 45 | 1847 | Christiana | Londonderry |

| Lindsay, Nancy | 4 | 1847 | Christiana | Londonderry |

| Mahoney, Catherine | 28 | 1847 | Wakefield | Cork |

| Mahoney, Jane | 2 | 1847 | Urania | Cork |

| Malone, Matthew | 4 | 1847 | Free Trader | Liverpool |

| McConaghy, Francis | 1 | 1847 | Christiana | Londonderry |

| McConnell, John | 1 | 1847 | Christiana | Londonderry |

| McCray, Alexander | 52 | Oct 7, 1847 | ||

| McCullough | 4 | 1847 | Christiana | Londonderry |

| McKinney, Mary | 24 | 1847 | Wellington | Liverpool |

| McMillan, Samuel | 1 | 1847 | Rosalinda | Belfast |

| Moore, Anthony | 50 | 1847 | Triton | Liverpool |

| Moore, Arthur | 3 | 1847 | Triton | Liverpool |

| Murphy, Ann | 1 | 1847 | Progress | New Ross |

| Murphy, Bridget | 16 | 1847 | Sarah | Liverpool |

| Murphy, Bryan | 27 | 1847 | Margaret | New Ross |

| Murphy, Catherine | 61 | 1847 | Avon | Cork |

| Murphy, Charles | 13 | 1847 | Lord Ashburton | Liverpool |

| Murphy, Darby | 3 | 1847 | Sarah | Liverpool |

| Murphy, James | 50 | 1847 | Sarah | Liverpool |

| Murphy, Johanna | 5 | 1847 | John Bolton | Liverpool |

| Murphy, John | 6 | 1847 | Gilmour | Cork |

| Murphy, John | 41 | 1847 | Naomi | Liverpool |

| Murphy, Mary | 50 | 1847 | Naomi | Liverpool |

| Murphy, Patrick | 50 | 1847 | Naomi | Liverpool |

| Neal, Daniel | 20 | 1847 | Avon | Cork |

| Neale, Margaret | 50 | 1847 | Avon | Cork |

| Neill, John | 50 | 1847 | Avon | Cork |

| Noonan, Dennis | 20 | 1847 | Avon | Cork |

| O’Hara, Catherine | 17 | 1847 | Naomi | Liverpool |

| O’Hara, John | 8 | 1847 | Naomi | Liverpool |

| Prendergast, James | 2 | 1847 | Avon | Cork |

| Roach, Mary | 60 | 1847 | Avon | Cork |

| Ryan, Allen | 18 | 1847 | Lady Flora Hastings | Cork |

| Ryan, Bridget | 6 | 1847 | John Munn | Liverpool |

| Ryan, Jenny | 3 | 1847 | Bee | Cork |

| Ryan, Lawrence | 48 | 1847 | Emily | Cork |

Burials at Grosse-Île: 1847

| Name | Age | Date of Death | County of Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allen, David | 57 | 9/16/1847 | Sligo |

| Anderson, John | 4 mos. | 9/6/1847 | Fermanagh |

| Anderson, Frances | 20 | 9/1/1847 | Fermanagh |

| Anderson, James | 5 yrs 9 mos. | 6/16/1847 | n/a |

| Ansley, Ann | 76 | 6/6/1847 | Armagh |

| Armstrong, Ann | 4 | 5/29/1847 | Fermanagh |

| Armstrong, John | 1 | 5/23/1847 | Cavan |

| Austin, Hamilton | n/a | 5/27/1847 | Antrim |

| Bailey, Eliza | 3 | 6/6/1847 | Tyrone |

| Baker, Mary | n/a | 7/1/1847 | n/a |

| Barnes, Jane | 30 | 6/12/1847 | Armagh |

| Barron, John | 5 | 6/6/1847 | Armagh |

| Barron, Robert | 7 | 6/14/1847 | Armagh |

| Benson, John | 45 | 5/26/1847 | Kilkenny |

| Blakely, William | 5 Months | 6/5/1847 | Fermanagh |

| Blank, William | 24 | 6/28/1847 | Tyrone |

| Bradshaw, Margaret | 25 | 6/13/1847 | Antrim |

| Brady, Joseph | 40 | 8/23/1847 | Monaghan |

| Brierly, Edward | 45 | 7/5/1847 | Cavan |

| Bryan, Judith | 6 | 5/14/1847 | Tipperary |

| Byrne, Thomas | 26 | 5/25/1847 | Mayo |

| Campbell, James | 3 | 6/5/1847 | Fermanagh |

| Clark, Mary | 22 | 9/24/1847 | Wicklow |

| Clarke, James | 35 | 9/2/1847 | Wicklow |

| Cootes, Margaret | 33 | 8/24/1847 | Cavan |

| Corbit, Lucinda | 18 | 9/22/1847 | Tyrone |

| Corrigan, Irvine | 5 | 6/18/1847 | Fermanagh |

| Corrigan, James | 22 | 6/8/1847 | Fermanagh |

| Davis, John | 50 | 5/31/1847 | N/A |

| Delanay, Henry | 15 | 9/5/1847 | Wicklow |

| Dodson, William | 19 | 7/5/1847 | Cavan |

| Douglas, Thomas | 7 | 6/7/1847 | Tipperary |

| Drumm, John James | 6 | 6/16/1847 | Castle Knokles |

| Earl, Edward | 30 | 9/15/1847 | Wexford |

| Elliot, Andrew | 50 | 6/6/1847 | Donegal |

| Fannen, Margaret | 11 Months | 5/20/1847 | Dublin |

| Farley, Francis | 8 Months | 6/2/1847 | Monaghan |

| Farren, Eliza | 19 | 5/22/1847 | Donegal |

| Finlay, Margaret | 18 | 8/23/1847 | Monaghan |

| Gallaway, Margaret | 1 Year 11 Months | 6/1/1847 | Antrim |

| Gault, Margaret | 11 | 6/2/1847 | Monaghan |

| Gilmour, John | 34 | 8/20/1847 | Armagh |

| Hawthom, John | 54 | 6/2/1847 | Armagh |

| Hayes, William | 41 | 8/30/1847 | Tipperary |

| Henry, James | 2 | 5/29/1847 | Monaghan |

| Hill, Francis | 20 | 9/2/1847 | Cavan |

| Hungerford, Francis | 13 Months | 5/20/1847 | Cork |

| Jameson, Eliza Ann | 12 | 6/30/1847 | Armagh |

| Kane, Ellen | 4 | 5/15/1847 | Mayo |

| Kennedy, Margaret | 3 | 5/28/1847 | Fermanagh |

| Kerr, Marianne | 42 | 8/20/1847 | Cavan |

| Kerr, Samuel | 50 | 6/4/1847 | Down |

| Lee, Ann | 22 | 9/10/1847 | Cavan |

| Lindsay, Ann | 20 | 8/18/1847 | Sligo |

| Macpherson, Ellen | 1 | 5/21/1847 | Armagh |

| McCall, John | 15 | 9/2/1847 | Monaghan |

| McComb, William | 7 Months | 5/29/1847 | Down |

| McMullen, Rosanna | 9 | 9/4/1847 | Louth |

| O’Hare, Sarah | 48 | 9/14/1847 | Tyrone |

| O’Reilly, Edward | 30 | 5/18/1847 | Fermanagh |

| Orr, Dorothy | 11 | 9/16/1847 | Tyrone |

| Patterson, Thomas | 15 | 8/29/1847 | Cavan |

| Prestage, Elle | 2 | 5/30/1847 | Wicklow |

| Purcell, Alexander | 2 | 5/21/1847 | Dublin |

| Reid, Elisa | 5 | 6/7/1847 | Roscommon |

| Reynolds, Margaret | 6 | 6/2/1847 | Antrim |

| Rice, Elizabeth | 55 | 6/7/1847 | Antrim |

| Robbs, Eliza | 12 | 6/15/1847 | Tyrone |

| Scott, George | 31 | 9/9/1847 | Cavan |

| Scott, Robert | 28 | 7/5/1847 | Cavan |

| Skews, John | 1 | 6/1/1847 | Cork |

| Soolivan, Margaret | 30 | 5/15/1847 | Tipperary |

| Sweedy, Robert | 34 | 9/1/1847 | Down |

| Tremble, Joseph | 25 | 9/10/1847 | Tyrone |

| Walker, James | 5 | 5/31/1847 | Armagh |

| Wilson, Mary | 54 | 6/4/1847 | Armagh |

| Wright, Margaret | 5 | 6/3/1847 | Cavan |

Marriages at Grosse-Île

| Name | Spouse | Religion | Occupation | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson, Jane | O’Neill, Maria | Catholic | Sailor | 8/4/1847 |

Baptisms at Grosse-Île

| Name | Date of Birth | Date of Baptism | County of Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baldwin, William | 2/9/1847 | 7/9/1847 | Waterford |

| Carrol, Catharine | 9/29/1847 | 10/1/1847 | Roscommon |

| Conway, Rosanna | 5/23/1847 | 6/1/1847 | Kilkenny |

| Gaffney, John | 6/12/1847 | 7/18/1847 | Roscommon |

| Kildy, John | 6/21/1847 | 7/18/1847 | Roscommon |

| Maher, James | 7/15/1847 | 7/15/1847 | Kilkenny |

| McBrien, Mary Jane | 8/16/1847 | 8/22/1847 | Fermanagh |

| Morisson, James | 7/11/1843 | 7/14/1847 | Down |

| Murphy, Molly | 8/21/1847 | 9/14/1847 | Antrim |

| Ryan, May | 5/5/1847 | 5/18/1847 | Tipperary |

| Sullivan, Patrick | 7/17/1847 | 7/17/1847 | Kerry |

| Woods, Owen | 4/21/1847 | 5/15/1847 | Monaghan |

A very sad but educational article. It should also be noted that Catholics could not live in Boston City proper in those trying times. However, as the “Famine” continued it is alleged that about one hundred and thirty six thousand (136,000) Irish arrived, mostly from Canada which changed the history and religion of Boston, possibly for eternity.