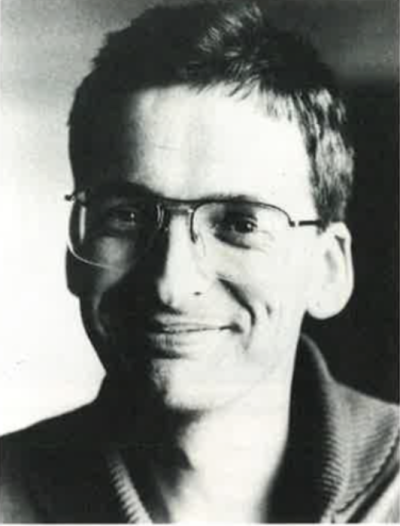

Irish writer Roddy Doyle’s book, Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha [Viking Press] won the prestigious Booker Prize last month, and the next day 28,000 copies were sold in England alone. Frank Shouldice profiles the Dublin author, whose movie The Snapper, directed by Stephen Frears, is currently being distributed in the U.S. by Miramax films.

Just seven years ago he worked as a primary schoolteacher in Kilbarrack, a working-class suburb on Dublin’s northside. With a largely undeveloped interest in writing he sent his first novel Your Granny’s A Hunger Striker to London publishers. The book did the rounds and was politely returned.

He then wrote a shorter novel heavy on dialogue. It was full of the colloquialisms one would hear around Kilbarrack or any working-class Dublin suburb. For dramatic purposes, Kilbarrack became Barrytown. Taking a bank loan of $7,500 he published the book himself through the Passion Machine, a sort of arts cooperative set up by friends with similar interests.

The Commitments was released by King Farouk with a print run of 3,500 copies. His friends noticed it. Some even bought it. But only when the title was picked up in London by Heinemann in 1987 did things begin to happen. As has been well reported by now, the book was adapted for film, directed by Alan Parker and scored well as a relatively low-budget movie. From his initial of $7,500, it is estimated that the book has earned its creator in the region of $100,000.

He wrote two plays: Brownbread and War, for the Passion Machine and both were extremely successful in Dublin. Doyle followed up with two more novels in what became known as the Barrytown Trilogy: The Van and The Snapper. Both were successful. The Van was nominated for a Booker Prize. Meanwhile the author adapted The Snapper for BBC TV and the drama did very well on television. In a follow-up move The Snapper, directed by Stephen Frears (My Beautiful Launderette and The Hit) was then released as a movie and is currently on release in the U.S.

And now the teacher’s fourth published work, Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha, has won the $35,000 Booker Prize, chosen by the panel as first of 115 novels from around the world. Although the Booker has been criticized in recent years for being too stuffy in its selection, it remains the most significant literary prize in Britain. If it has been stuffy before, the panels pick this year has swung firmly from the literary to the popular. This is the first time an Irish writer claimed the prize.

And even while the ceremonies were going on in London, Doyle’s four-part TV script, Family was being filmed in Dublin by BBC on a $3.5 million budget. Set in the family home of a small-time crook, Family is bleaker than previous works. “It’s quite depressing for the first two episodes but it gets better at the end,” says producer Andrew Eaton.

Roddy Doyle gave up teaching this year so he has the time to write. He is certainly without the pretensions fulltime writing might carry — while the 35-year-old is unlikely to lose the run of himself, it seems he can do no wrong these days.

Inevitably there are literary discussions — of the heated variety — on the merits of Roddy Doyle’s work. Its appeal is broad and undisputed. Steeped in reality, the situations and dialogue are so naturalistic that some Dubliners are delighted to see their lives accurately represented on the page. For others, the situations and dialogue are too familiar to be considered unusual or particularly special.

Curiously, reviewers and readers in Britain have taken Barrytown to their collective bosom. Maybe they find the language humorous and charming — to the uninitiated, acquiring the rhythms and vocabulary of Dub-speak is a sort of exploration in itself, just as it would be with the dialects of Liverpool or Glasgow. Those who enjoy the exploration tend to love the adventure.

Doyle is often asked to explain his emphasis on dialogue. Characters, he contends, come alive for him when they speak. The inner voice of each book depends on whoever is the central character. “In say, The Van, I wanted it to be Jimmy Sr.’s book,” he suggested. “The style of sentences depends on him thinking rather than me writing.”

In Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha, the narrator is a 10-year-old boy growing up in 1968 Barrytown. We see the world through the boy’s eyes, join in his games and suffer the domestic hardship or a painful parental separation. As one would expect, the narrative is rich in humor, often put across like a series of vignettes illuminated by a childish sense of innocence and curiosity. And if you find the narrative voice convincing as belonging to a young boy, the book certainly works. For many readers this is its strength.

In some of the best passages there is no evidence of a 35-year-old writer at work — childishness can be a literary virtue! He writes:

“She listened to him much more than he listened to her. Her answers were much longer than his. She did two-thirds of the talking, easily that much. She wasn’t a bigmouth though, not nearly; she was just more interested than he was even though he was the one that read the paper and watched The News and made us stay quiet when it was on, even when we weren’t making any noise. I knew she was better at talking than him; I’d always known that.”

Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha is, by comparison with the three earlier novels, a more mature and complex book. The vignettes — some touching, some charming, some contrived — are strung together with a sense that the young narrator, Paddy, is growing up.

As other authors have shown — such as Gunter Grass in The Tin Drum or Sue Townsend in the highly successful Adrian Mole series — looking through the eyes of a child is a great way to reveal the inconsistencies of the adult world.

Perhaps that’s why feminist Australian author Germaine Greer was the novel’s most ardent supporter on the awards panel last month. At the close of the ceremony, Greer could not contain her admiration for the Dublin author. “Roddy Doyle,” she enthused, “is too good for the Booker.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the January/February 1994 issue of Irish America. ♦

Leave a Reply