From witch hunts and huddled masses to the White House– 20 significant moments in the history of the Irish in America.

1688: Witch Hunt

Goody Glover, an Irish woman, was hanged as a witch four years before the infamous Salem Trials of 1692 (as illustrated left). Glover, an Irish laundress who came to Salem, Massachusetts via the Caribbean, was arrested, tried for bewitching, and hanged when Martha Goodwin, 13, began exhibiting bizarre behavior after a row with Glover. Perhaps Glover’s only crime was that she spoke Irish and not the language of her Puritan prosecutors.

1776: Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence has more of an Irish touch to it than you might think. The actual Declaration was written in the hand of Irish-born Charles Thomson. It was read aloud to the people for the first time by John Nixon, a native of Ireland, and printed by Irish-born John Dunlap. At least three signatories were of Irish birth — Matthew Thornton, George Taylor and James Smith. Nine were of Irish origin, including Edward Rutledge, Thomas Lynch, Thomas McKean, George Read, Robert Treat Paine and Charles Carroll (pictured right), who was the only Roman Catholic to sign the Declaration and the last to survive.

1822: Andrew Jackson Elected President

Andrew Jackson was the first Irish-American to be elected president. Jackson’s parents emigrated from Castlereagh, Co. Antrim. Jackson was born two years later on March 15, 1767; his mother was widowed while pregnant with him. Jackson fought in the Revolutionary War when he was just 13. He and his brother were captured and contracted small pox. His mother managed to have her boys rescued, but she herself died while tending troops.

1775-1781: The Revolutionary War

It is estimated that one-third to one-half of George Washington’s army were Irish born or first-generation, including 1,492 officers and 26 generals, 15 of whom were Irish natives, chief among them Commodore John Barry (pictured left), from County Wexford, who became the “Father of the U.S. Navy.” Washington is quoted as saying: “When our friendless standards were first unfurled, who were the strangers who first mustered around our staff, and when it reeled in the light, who more brilliantly sustained it than Erin’s generous sons. Ireland, thou friend of my country in my country’s most friendless days, much injured, much enduring land, accept this poor tribute from one who esteems thy worth, and mourns thy desolation. May the God of Heaven, in His justice and mercy, grant thee more prosperous fortunes, and in His own time, cause the sun of Freedom to shed its benign radiance on the Emerald Isle.”

1825-1832: The Erie Canal

The Erie Canal was built by “Irish power” under the inspiration of New York Governor DeWitt Clinton, the grandson of an Irish immigrant. It is said, “For Every Mile of the Canal, an Irishman Is Buried.” The canal diggers were mostly Irish immigrants. The work was grueling and dangerous. Hundreds died from various microbes festering in the mud and stagnant water — malaria (or “Canal Fever”) and acute diarrhea. Many were buried in unmarked graves along the canal, or in mass graves at nearby cemeteries. Similarly, in New Orleans, the New Basin Canal was built between 1831-38 using Irish immigrant labor and claimed many lives.

1861-1865: The Civil War

The Irish fought on both sides of the Civil War, but predominately with the Union Army. One of the most famous units of the Northern army was the Irish Brigade. Thomas F. Meagher of the New York 69(th) Regiment created the brigade, which included the 63(rd), 69(th) and 88(th) New York Infantry Regiments. In the fall of 1862, the 28(th) Massachusetts and the 116(th) Pennsylvania were added. Also, the 29(th) Massachusetts was attached to the brigade during the campaigns of the Peninsula and Antietam. The Irish Brigade’s most famous fight was the Battle of Fredericksburg, where it suffered enormous casualties in repeated gallant charges at Marye’s Heights. Ironically, the famous Celtic cross monument to the Irish Brigade at Gettysburg was sculpted in 1888 by an Irish immigrant from Louisiana who fought on the Confederate side at Gettysburg.

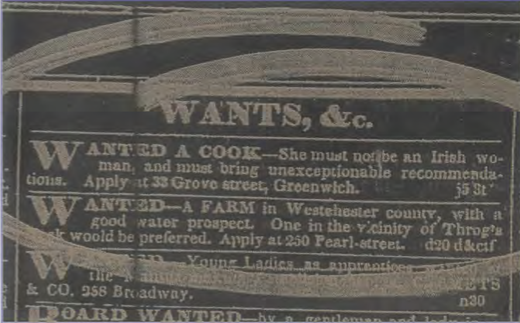

1845-1851: The Famine Irish

In 1845 a devastating potato blight swept across Ireland destroying the crop on which most of the Irish poor depended. In the next six years more than a million died from hunger and disease. Hundreds of thousands were evicted from their homes and left to wander the roads. Over one and a half million fled Ireland for abroad, many braving the horrendous boat journey on “coffin ships” to America and Canada. Thousands died of ship’s fever en route and were buried at sea, and in 1847, the worst year of the famine, thousands more perished in quarantine on Canada’s Grosse Ile, and were buried in mass graves on the island.

The Famine Irish were the first large group of immigrants to experience the ridicule and discrimination that many others would later endure. They were poor, unskilled, often uneducated, and many doors were closed to them. They were willing to work, but many “IRISH NEED NOT APPLY” signs kept them from better jobs. Nevertheless, they were ready to take on most jobs, usually any manual work that was available. Gradually, they were able to improve their conditions and expand their influence and power.

1859: The Comstock Lode

The richest known silver deposit in the U.S. was discovered in Nevada by two Irish laborers, Peter O’Reilly and Patrick McLaughlin. A fellow miner, Henry Comstock, stumbled on their find and persuaded O’Reilly and McLaughlin that it was his property. Ironically, Comstock sold prematurely for $ 11,000. The lode produced more than $500 million worth of silver, a large share of which went to the Irish-American Big Four: James Flood, William O’Brien, James Fair and John Mackay.

1879: The Unions

In 1879, Terence Powderly, a son of Irish immigrants, was elected head of the Knights of Labor, a national association of labor unions. Under his stewardship, the association grew to include more than 700,000 members. With the increase in numbers, the unions were better able to facilitate strikes and dramatically improve working conditions for U.S. laborers. At the turn of the twentieth century, Sam Gompers and P.J. McGuire, a second-generation Irish-American, co-founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL). By 1910, nearly half the AFL’s 110 member unions were led by Irish-born or Irish-American men. In 1920, union membership rose to new heights, reaching five million nationwide. In 1955, George Meany, who began as a plumber’s apprentice, became the first head of the merged American Federation of Labor — Congress of Industrial Workers (AFL-CIO), the nation’s largest labor organization. Today the AFL-CIO, which represents more than 13 million working Americans, is directed by John Sweeney, a second-generation Irish-American.

1865-1869: Working on the Railroads

Mostly Irish-American ex-soldiers were employed on transcontinental railroad construction at wages averaging $3 a day. As the song put it, “Poor Paddy works on the railroad.” The joining of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroad took place on May 10, 1869.

1869-1883: The Brooklyn Bridge

Constructed chiefly by Irish contractors and laborers and hailed as “the eight wonder of the world,” the building of the Brooklyn Bridge was initiated by a Kilkenny-born building contractor and newspaper publisher William C. Kingsley.

Kingsley and Abram Hewitt, a businessman and later a politician, persuaded the state legislature to build the first “great bridge” over the East River to link the then separate cities of Brooklyn and New York.

Many workers, including John Roebling, the German immigrant who designed the 3,460-foot-long bridge, suffered from “caisson’s disease,” now known as the bends, but often returned to work after they recovered. Some 27 workers died from work-related accidents and illness, which Roebling claimed reflected “the perfect equilibrium of nature.” When Roebling died in an accident, his son Washington continued his work.

1914-1918: World War I

Many Irish-Americans fought in the Great War, hut none were more celebrated than those who fought with the New York Fighting 69th, an Irish-American regiment which was incorporated into the 165th Infantry during WWI. The men fought with distinction and had a combat record that was unmatched. One of its most famous members was William “Wild Bill” Donovan (pictured above), who used his experiences in both WWI and WWII to create The Office of Strategic Services, the predecessor of the CIA. Another distinguished Irish-American during the war was Private John Joseph Kelly from Chicago, who was among an elite group of soldiers to receive two Medals of Honor. Kelly single handedly attacked a gunner’s nest, killed two enemy soldiers, and rescued eight prisoners. He was awarded both the Army and Navy Medal of Honor for his heroic actions.

1935: Braddock Wins Heavyweight Championship

Irish-American James J. Braddock, recently portrayed by Russell Crowe in the movie Cinderella Man, was an inspiration to fellow Americans during the Depression. Impoverished, working on the docks and with a hand injury that had supposedly ended his boxing career, Braddock, in 1934, was called upon as a late replacement to fight heavyweight contender Art Lasky with only two days to prepare. Braddock shocked the world, beat Lasky, and went on a run of wins that would see him beat Max Baer for the heavy weight title in 1935. Braddock held the title for two more years before losing it to Joe Louis. “Irish Jim” personified the good-guy underdog who made it. He gave hope to millions in a time of unparalleled poverty and suffering in America.

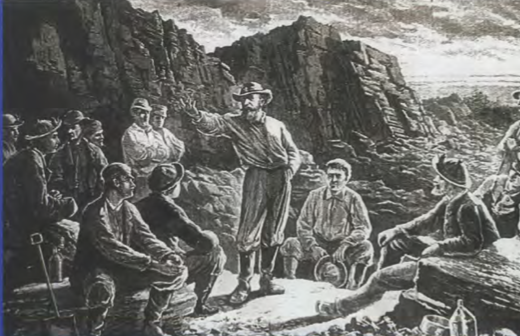

1876: The Molly Maguires

Nineteen of the Molly Maguires, a secret society of Irish miners who had been waging a campaign of terror against the oppressive mine owners and managers of the western Pennsylvania coalfields, were hanged. The group had been infiltrated by another Irishman. James McParland from Co. Armagh, who as an agent of the Pinkerton Detective Agency, was sent to spy on the group. McParland became an intimate friend of the group’s leaders, and as a result of his testimony nineteen were arrested, tried and convicted and executed.

An advocate of non-violent protest but no less passionate a defender of miner’s rights was Mary Harris “Mother” Jones. In a time when few women were activists, she championed the miners cause and often risked arrest and her own safety in her support for their struggle for safer working conditions and better pay. She was no stranger to tragedy. Her husband and four children were killed in the yellow fever epidemic that swept through Memphis’ Irish section in 1867, in October 1871 she lost her home and dressmaking business in the Chicago fire and her father died only two months later. While working as a dressmaker for the rich and living among the poor, Jones became enraged at the disparity between the classes and spent the rest of her life travelling the country raising the hopes of workers and supporting their strike action for better treatment. She represented the miners in Congressional hearings and remained outspoken in her support for improving the lot of the working man right up to her death in 1930.

1941-1945: World War II

Of the thousands of Irish-Americans who served in World War II, one of the most tragic stories involves a family from Waterloo, Iowa. Thomas and Alleta Sullivan had five sons (pictured above from left to right), Joseph, Francis, Albert, Madison and George. Though not recommended, there were no rules against siblings serving side by side, and all five brothers joined the Navy together. “As a bunch, there is nobody that can beat us,” eldest George used to say. All were serving on the USS Juneau when fighting broke out in Guadalcanal on November 13, 1942. Ironically, by that time the brothers had intended to split up but had not gotten round to it when a Japanese torpedo destroyed their ship. Four brothers died instantly; George survived with others on a raft. Days of extreme heat and thirst made the soldiers delirious, and when George decided to go for a bath one night his movements in the water attracted a shark and he was never seen again. Despite their tremendous loss the Sullivan parents toured extensively making speeches on behalf of the war effort. The USS The Sullivans was named in their honor and christened by their mother Alleta Sullivan in April 1943. The Sullivans loss was the greatest sacrifice made by any one family in World War II and the Navy introduced the Sullivan Law, which prevented brothers from serving on ships together.

Another great Irish-American hero was Second Lieutenant Audie Murphy. Refused for service by both the Marines and the Navy, Murphy was finally accepted into the Army in June 1942. Due to his slight stature the Army tried to make him a cook but he stubbornly refused and went onto fight nine major campaigns and was wounded three times. Murphy won a Medal of Honor for his actions on January 26, 1945, when he stood atop a burning tank destroyer and, though wounded, single-handedly held off six German tanks. At the end of the war Murphy accepted an invitation from Jimmy Cagney to join him in Hollywood where he became a movie star.

1961-1963: John F. Kennedy Presidency

John F. Kennedy was sworn in as the 35th president on January 20, 1961, forever banishing the “No Irish Need Apply” signs. Born in Brookline, Massachusetts, on May 29, 1917, Kennedy was the first and only U.S. president who was Catholic. At 43, he was also the youngest. In June, 1963, Kennedy visited Ireland, the first sitting U.S. president to do so (Ulysses S. Grant visited Northern Ireland after he was out of office.) Kennedy visited New Ross and stood on the place where his great grandfather Patrick Kennedy last stood before he boarded a ship to America. John promised that he would return to Ireland in the springtime. It was not to be. On November 21, 1963, Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas.

1965: Immigration Act Passed

In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson signed a bill that has dramatically changed the method by which immigrants are admitted to America, and shifted the focus to non-European countries, especially those of the third world. The bill, first put forth by President Kennedy, significantly changed the course of Irish immigration. For the first time, immigration from Western Hemisphere countries was limited to 120,000 annually. With poor economic conditions at home, many Irish chose to come to the U.S. anyway, and by the 1980s hundreds of thousands undocumented Irish would be living in the U.S. ~

1992-2000: The Clinton Years

President William Jefferson Clinton did more to bring peace and prosperity to Northern Ireland than all the other U.S. presidents combined. Clinton came through on a campaign promise to give Gerry Adams a visa, which led to the IRA ceasefire. In November 1995, 15 months after the ceasefire, he visited Northern Ireland, further helping to heal the divide. He followed through by organizing an Economic Conference on Northern Ireland and the Border Counties, in Washington, D.C., that included delegates and political leaders from both communities in the North. He appointed former Senator George Mitchell, first as economic advisor and then as chairman of the inter-party talks, a move that ultimately led to the Good Friday Agreement, which was signed on April 10, 1998.

1980s: Donnelly and Morrison Visas

When illegal immigration from Ireland had reached a crisis point in the U.S., Massachusetts Congressman Brian Donnelly (pictured above) was successful in pushing through a temporary “visa lottery” program with a large portion of the quota available to the Irish. Congressman Bruce Morrison of Connecticut got the program extended and the number of visas increased. In all, it is estimated that some 50,000 Irish people took advantage of the Donnelly and Morrison visas and went on to become American citizens.

2001: 9/11

The face of Irish America was forever changed on September 11, 2001, when Muslim extremists flew two planes into New York’s World Trade Center killing 2,874 people, including 343 firefighters and 60 police officers. In the Irish tradition it was the haunting sound of bagpipes and the roll of drums that accompanied many of the funeral processions, as the pipes and drums bands of the FDNY and the Police Department played a final farewell to colleagues. We will never forgot those we lost, including friends of the magazine, firefighter Tom Foley, and Chris Duffy and Joseph Barry from Keefe, Bruyette &Woods, who just two months before, on July 11, had attended our annual Wall Street 50 dinner at WTC’s Windows on the World restaurant.

Leave a Reply