In eleven years we will reach the centenary of the 1916 Rising, the revolutionary crucible of present-day Ireland. Independence did not arrive until 1922 — along with partition and the seeds of Northern conflict — but at this stage we are at least four generations into modern statehood. Shouldn’t 83 years be long enough for us to know where we are and, even possibly, where we’re going?

We’re no different from other countries insofar as Ireland is constantly evolving as a nation. Unlike most countries however, what’s happening right now represents the most significant transformation since Irish independence. If you want to get a handle on where things stand, you could probably squeeze the last century into the past twenty years. It’s been that dramatic. And if you don’t believe me, the next time you visit you’ll see for yourself.

At 42 years of age the past two decades bisect my own life, about five years of which passed memorably in New York. I left Dublin in the mid-1980s, a time when there was nothing new about going away. A lack of work prospects maintained a pattern that was well established since the 1950s. People continued to leave in droves through the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, bearing one-way tickets bound for Britain, for America or for Australia. Some came back but many didn’t. What was there to come back for? Ireland was one of the poorest countries in Europe and there was no sign of a turnaround.

Even when I came back to Dublin in 1992 there wasn’t a hint of the sea change that was about to take place. Where did we stand back then? People were still leaving in their thousands. Many pinned their hopes of emigrating to the U.S. on the Donnelly and Morrison visa lottery programs of the ’80s and ’90s. But for many Irish, Continental Europe began to look more inviting if the obstacles of a second language could be overcome. At home, unemployment remained high and optimism ebbed low. The outlook was bleak, a forecast for more of the same.

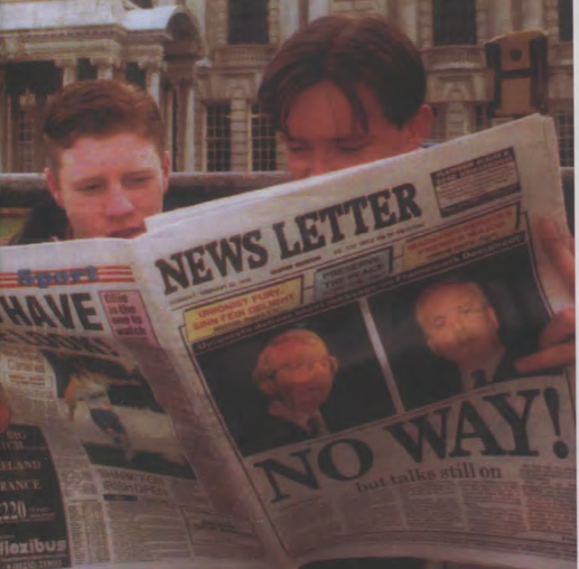

At a cultural level we struggled to put a stamp on our national identity. Our definition of being Irish still revolved around stating that we were not British. We found it easier to say what we were not than to settle for what we were. The virtual loss of our own language did not help. We were entrenched in history and firmly tied to the Troubles, even if the daily realities of the North had become far more remote to the South than the 100 miles from Belfast to Dublin.

It’s asking a lot of artists, entertainers and sports stars to assume the role of cultural ambassadors, but we needed all of them to break new ground and to provide a more contemporary version of Ireland than Joyce, Beckett, Wilde, Shaw (all of whom, conspicuously enough, had left home shores, never to return).

International successes like U2 and Guinness afforded us catch-phrase reference points. In 1990, for the first time ever, a Republic of Ireland soccer team qualified for the World Cup in 1990 — the Northern Ireland team had already done so on three occasions. Factors like these might seem unimportant but they underline how ill-defined we were as a nation and how low our profile was abroad.

When Ukraine won the much-maligned Eurovision Song Contest last year we could understand their delight as a matter of international recognition. We’ve been there ourselves (seven times), but thankfully we’re moving on. Other achievements, like the Academy Award-winning My Left Foot, and Tony Award-winning Dancing at Lughnasa, bespoke a newer domestic confidence.

But a modern identity would have floundered without an improved economic picture. That transformation has been hackneyed into shorthand as “The Celtic Tiger.” Coinciding with the dot.com period, it took a major shift in Irish industryaway from agriculture and into telecommunications and pharmaceuticals. Thanks to remarkable success in attracting investment from overseas — mostly from the U.S. — growth in the telecom and computer-related sector created opportunities for an educated workforce through the late 1980s and early ’90s. And through that time EU development funds were made available to begin a major overhaul of a national infrastructure that was archaic by European standards.

The immediate impact was to slash unemployment and reduce emigration. Most of the jobs were created in the greater Dublin area — and to a lesser extent Galway, Athlone, Limerick, Cork — so that an increasingly mobile workforce tilted the demographic spread decisively eastward to the capital.

Buoyed by an economic revival, government borrowing dropped, cutting bank interest rates from crippling highs to record lows. This prompted corresponding booms in the property market and construction. The peace dividend in Northern Ireland, however tenuous, lent stability to the island as a place to reside or invest.

In a matter of years the Republic became a place to stay rather than a place to leave. Budget airlines made travel easy and affordable, making the country less isolated than before. By the late ’90s thousands of emigrant families were coming back to settle permanently. They brought back a different outlook, life experience from abroad and a realization that Ireland is not the center of the globe.

They also brought their life savings with them. For a country perilously close to bankruptcy in the 1970s, there has never been so much money in circulation. Living standards have risen, but the cost of living — especially housing — bears no relation to the 1980s. After years of receiving EU assistance, Ireland is now a net contributor to EU funds. Economically, it seems we have turned the corner.

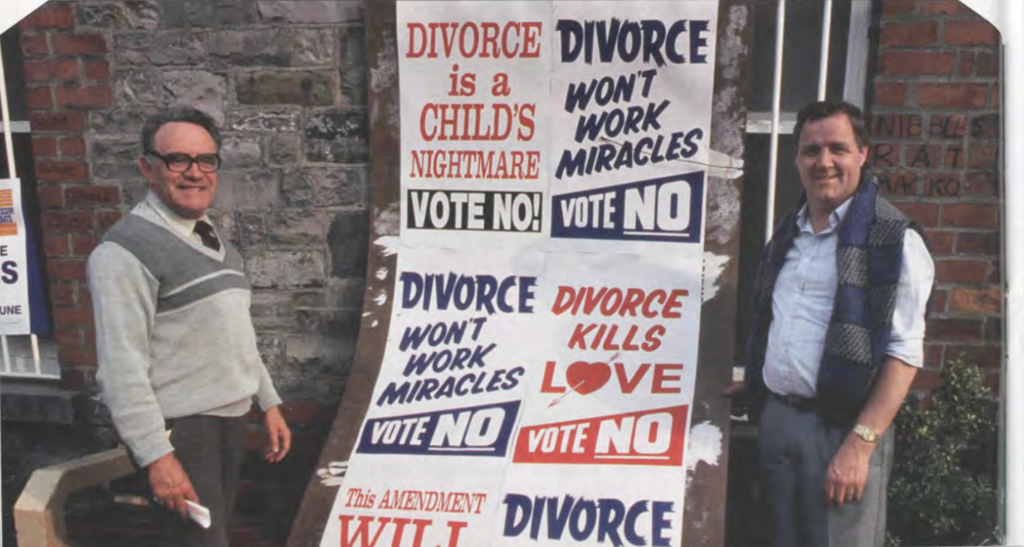

Yet the economic revival masks other concerns and confusions. The virtual implosion of the Catholic Church has removed a traditional pillar from Irish society. For a country supposedly comprising 90 percent Catholic citizens — the figure is farcically inaccurate — the question is not whether the Catholic Church still has influence but what has replaced it. This is plainly obvious, but not everybody is ready to accept it.

For instance, media coverage of public reaction here to the passing of Pope John Paul II was massively exaggerated. It suggested, wrongly, that “young people of Ireland” — as the Pontiff addressed them on his visit here in 1979 — were as committed to the Church as previous generations. The fact is that Pope John Paul II presided over a conservative Vatican so out of touch with Ireland’s changing society that had he returned a Second time he might not have recognized the place.

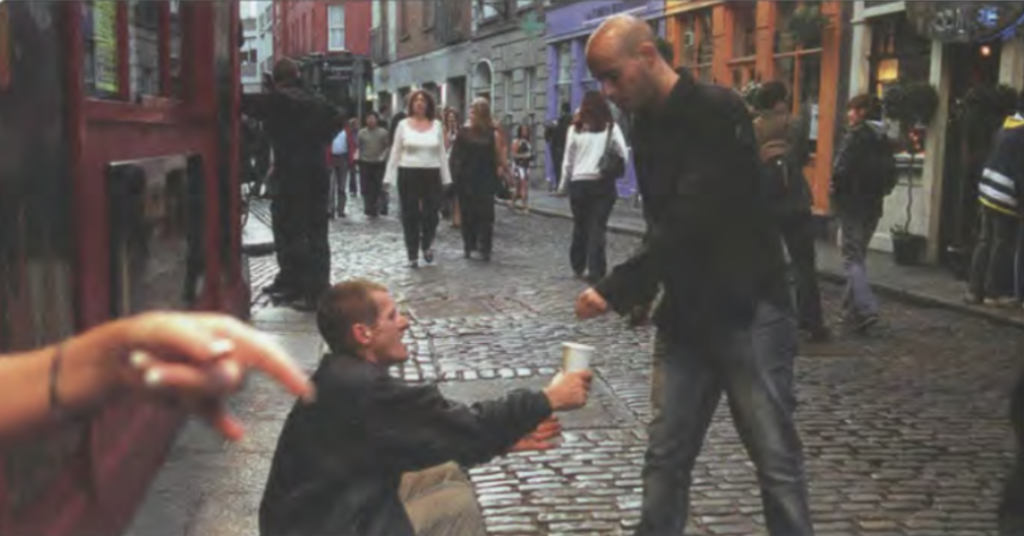

For the Church to collapse at a time of increased wealth means we have become as materialist as any secular country in the world. The term “Celtic Tiger” also covers up a shocking polarization between rich and poor. It is a mystery quite how economic statistics are arrived at, but for thousands of our poor and homeless, the notion that Ireland now ranks alongside Switzerland and Sweden as one of the world’s wealthiest nations is worse than a bad dream. We may never have seen so many brand new deluxe cars on our clogged-up roads, but the rising tide does not lift all boats. Poverty has not disappeared. It’s just we don’t notice it any more.

This has all happened so quickly that it feels like generation gaps are getting shorter. The spectre of unemployment — almost a given in the 1980s — is an unknown quantity to present-day school leavers. Contrasting then and now is to sound like their grandfather. How strange it is to think we’re still talking just twenty years ago.

Recent visits to Glasgow and Bucharest reminded me of Dublin during the recession — Glasgow for its dilapidation and Bucharest for its disillusionment. What struck me particularly about Romania was that most engineering and medical graduates emigrate as soon as they qualify. In Ireland we used to call it “the brain drain.” The phrase hardly did justice to those who remained behind, but such an educational diaspora is deeply destructive to any emerging nation.

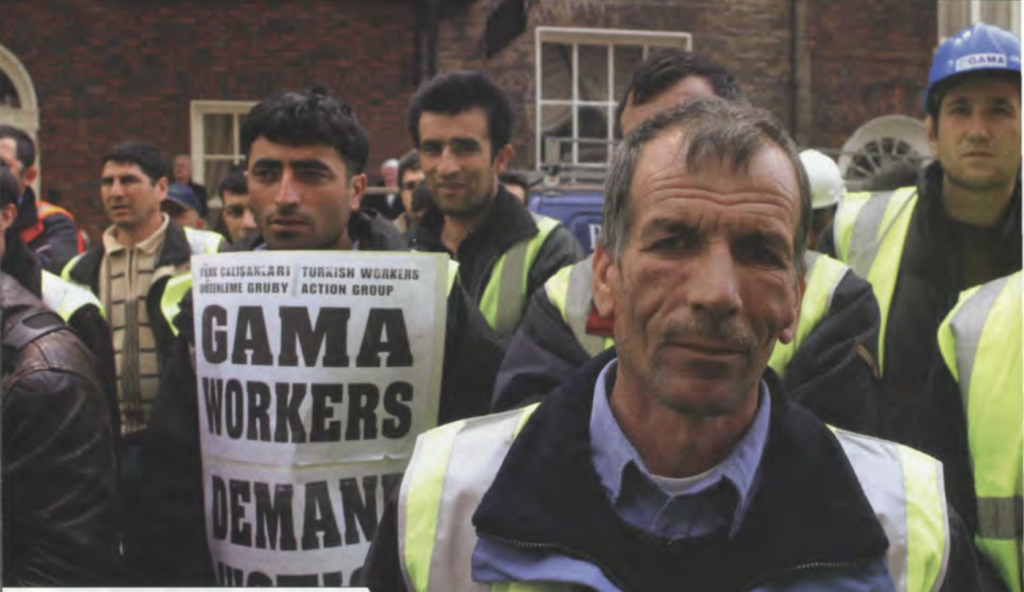

Significantly, there is now a net inflow of people to Ireland for the first time in our history. Our industrial growth demands a fresh workforce, and because Irish family sizes have declined, we need the immigrants who come here. This is a multicultural society, yet we still consider ourselves a homogenous people. Our national confidence has not yet found a way to integrate expanding Chinese, Polish, Nigerian, Romanian, Lithuanian, Russian, Latvian and Indian communities. In the past, Irish people abroad have been confronted by racism; now that we are a “host nation” we need to put that bitter experience to better use.

How much is this country going to change? Who knows? Anglo-American influences are so pervasive that you might occasionally wonder if we are the 51(st) state or a regional audience for the BBC. We do fit more comfortably into the modern world, and if there is a price, it’s that we have become less unique. Maybe that’s not such a bad thing. Either way, it’s a difficult balancing act for an island people. We’ve seen it happen at a micro level on the Irish-speaking islands off the west coast, but at national level, the global village is our live-in neighbor.

More than any other time in the past hundred years, the last two decades provided the greatest spark and the greatest challenge. If we want to be a modern nation, how true can we stay to tradition? Therein lies the tension and the dynamic. The country is not quite a century old, but the current phase of development demands we find a way to negotiate our past and present and locate our island culture on the world stage. Either way, interesting times ahead ♦

Leave a Reply