Niall O’Dowd writes about Bill Flynn’s extraordinary role in the Irish peace process.

On February 12, 1994, Bill Flynn and his trusted friend and associate Bill Barry drove to Belfast to meet with Gerry Adams. (Barry was Chairman of Barry Security Services after leaving an exciting career with the Federal Bureau of Investigation.)

It was directly in the wake of the granting of a visa by the U.S. government to Adams, allowing him to come to America. His 48-hour visa visit had won international headlines, and Bill Flynn’s role in securing that visa had been widely covered.

The Northern Ireland conflict was center stage worldwide placed there because Bill Flynn had helped lead the audacious strategy to win an American visa for Adams at a time when he was considered an international pariah.

Flynn and Barry’s appointment was at Connolly House in West Belfast and Flynn was behind the wheel of a rented Mercedes.

They were behind time and turned off the M1 motorway close to their destination. Suddenly they came upon a burning building, with tanks and soldiers with machine guns everywhere.

Their destination had just been hit with an RPG rocket launcher fired by Loyalist paramilitaries. If they had been on time for their appointment they would have been in the building when the rocket hit. If Bill Flynn ever needed confirmation that it was a tough and dangerous business he was involved in in Northern Ireland, he received it that day.

Given his Northern Irish roots and his pride in his Irish heritage, it is hardly surprising that Bill Flynn became interested in the conflict there. Unlike millions of other Irish Americans, however, Flynn did not confine his interest to a sentimental attachment on St. Patrick’s Day or an occasional tip of the hat to his Irish roots at some dinner or other.

Typical of the man, he became involved at the deepest level possible after weighing the many options he had about where and when to get involved.

Too many Americans allowed their sentiment and family history to cloud their judgment when it came to Northern Ireland. Bill Flynn would not make that mistake.

His approach was typical of his successful business career, a great deal of analysis followed by a direct and clear-cut strategy. If mistakes were made, they were corrected. Friendships on all sides of the conflict were cultivated and acted on.

“This was never going to be an emotional outreach, rather it was going to be a carefully planned strategic involvement designed to achieve maximum impact,” says Flynn.

Professor Fergal Cochrane of the Institute for Peace and Conflict Research at Lancaster University in Britain has argued that it was Irish-American “soft power” as exemplified by Bill Flynn and others that transformed the Northern Ireland peace process. In his 2007 article “Irish America, the end of the IRA Armed Struggle and the Utility of Soft Power,” Cochrane makes the telling point that hardline Irish-American organizations such as Noraid had nothing like the impact that men like Bill Flynn and Charles Feeney, highly successful businessmen, had on the peace process when they became involved.

In early 1993, just as the Northern Ireland issue was beginning to heat up, Bill Flynn made the key decision to become Chairman of the National Committee on American Foreign Policy, a group with great standing in the American foreign policy world. This gave him a powerful independent position, which he was to use to great advantage.

“The National Committee brought together a very fine group of foreign policy experts,” Flynn says, “and I believed it was a very useful forum for discussions such as we wanted to hear about how peace might come to Ireland or one of the many other trouble spots around the world. I saw it as a great venue for different points of view to be expressed to us.”

Since June 12, 1991, Flynn had been aware that a major effort was underway to create a new opening for peace in Northern Ireland using Irish-American influence as a major lever. On that date he had met with a leading Irish-American figure, a close friend and confident (who asked that his name be kept private) who outlined the strategy to him.

It would involve Irish America becoming an honest broker between the Republican movement and the powers that be in America. It was a high-risk strategy but it appealed to Flynn because he could see the logic behind Irish-American soft power.

“Irish America had never become involved in a direct way, acting as a broker rather than cheerleading one side or the other,” he says now. “This was an outstanding opportunity to think outside the box.”

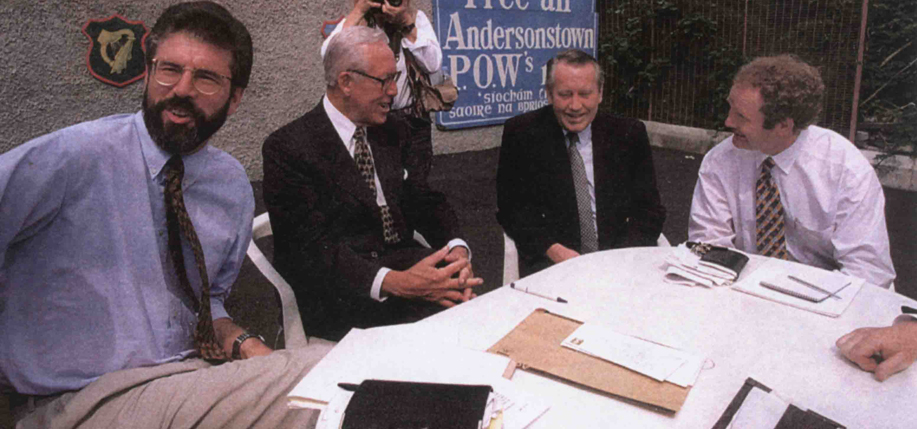

The first crucial test of the new departure occurred when the Americans for a New Irish Agenda (ANIA) as the deputation was known, arrived in Belfast on September 3, 1993. The group consisted of Flynn, businessman Chuck Feeney, former Congressman Bruce Morrison, publisher Niall O’Dowd and labor leader Joe Jameson.

The election of Bill Clinton had dramatically changed the equation between America and Ireland. Clinton was on record as proposing a far more involved stance on the issue of seeking peace in Ireland. The New Irish Agenda group were about to be the instrument of that.

Through a series of secret contacts and long-distance communications, a secret document was produced which outlined the willingness of the IRA to conduct a week-long ceasefire starting at midnight on Friday, September 3, while the American delegation was in Ireland. Their intent was to show the American administration that the IRA were interested in a major outreach to America.

“It was smart thinking on their part,” says Flynn. “The Republican movement needed to end their international isolation, and we were the ones who were going to try and help them achieve that.”

Prior to their visit North, the group spent two hours in Dublin with new Taoiseach (Prime Minister) Albert Reynolds who threw everyone else out of the meeting and told the group he was making real progress with his British counterpart John Major and he needed American help to bring Sinn Féin in from the cold.

It was the beginning of a great friendship between Flynn and the Prime Minister. “Albert saw things not just as a politician, but also as a successful businessman, which he was before he ever entered politics,” says Flynn. “We connected right away. I loved his straightforward analysis and I think he had a deep affection for America, which really helped.”

They also went to see Jean Kennedy Smith, the new U.S. Ambassador to Ireland, and Flynn made another invaluable connection. “She was just getting used to the job,” he remembers. “But I could see she had a lot of determination and she wanted to make a difference.”

One of the key meetings was with Loyalist political figures in Belfast and again Flynn found himself meeting an unlikely cast of characters that included Gusty Spence, an icon in Loyalism; David Ervine, Spence’s successor as head of the Progressive Unionist Party, and Gary McMichael who led the political wing of the Ulster Defense Association.

“They really opened my eyes and those of our delegation.” Flynn remembers. “They talked about the poverty and depression on the Shankill Road and in the major Loyalist areas. It was a real change to hear their side of it, how they felt Ian Paisley had misled their communities and how they were also bearing the brunt of the violence. They were so articulate and committed, they really made an impression.”

It was the beginning of an important relationship for both sides. Bill Flynn took it upon himself to include the Loyalists in every future move he made in Northern Ireland. They deeply appreciated the inclusion after years of exclusion.

The meeting with Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness on that trip was the key moment. There was a huge media presence outside the meeting place, but once inside it was all business.

“It was a long and very intense meeting,” Flynn remembers.

The Americans laid out their strategy that every move by the IRA towards peace would be matched by political benefits in the United States, including a visa for Gerry Adams as President Clinton had promised. While they themselves could not promise such a visa, they made clear they would be ready to fight hard for it.

“I was very impressed with Gerry Adams,” Flynn now remembers. “He struck me right away as a man of his word, and there is nothing more important. I have never wavered in that belief since.”

The unofficial ceasefire held while the group was in Ireland. From September 3 to September 11 there was no IRA activity. Back in Washington, through the network created by the visiting Americans, the news reached directly into the highest levels of the White House. The first seeds had been sown.

In the months that followed, the peace process began to pick up steam. The British government admitted it had conducted secret talks with Sinn Féin, and it was leaked in Ireland that the two governments had been working on a joint declaration plan to push progress in the North.

The American delegation needed to decide on strategy, and at a midtown meeting in a New York pizza parlor, the decision was made to pursue a visa for Gerry Adams.

It was a long shot at best. Previous applications had all been turned down. While there was significant contact with the White House, the idea of an Adams visa before an IRA ceasefire was still considered too risky for the new administration. The British Embassy was actively canvassing against any gesture towards Sinn Féin.

Bill Flynn had the perfect vehicle, however, as Chairman of the National Committee on American Foreign Policy (NCAFP). He himself had impressive credentials for hosting the event, having sponsored conflict resolution conferences on the Middle East and Ireland previously. His friendship with a clutch of Nobel Prize winners such as Elie Wiesel also gave him enormous credibility.

Taking the issue out of its Irish context and placing it in an international dimension was critical. Flynn put the proposal to invite all the Northern Ireland leaders, including Gerry Adams, to come to America and speak at a peace conference to the NCAFP board. Some of the members were highly dubious about inviting an “international terrorist” to speak before them. A few years earlier, Margaret Thatcher had spoken at an NCAFP event. Henry Kissinger was an honorary chairman and made clear he did not like the idea. But Flynn persevered.

“It’s important when you commit to something that you give it everything,” he remembers. “I knew it was the right thing to do and I was determined to do it.”

Flynn set the date of February 1, 1994, as the conference date and booked the Waldorf Astoria. He invited all five leaders of the major Northern Ireland parties. The invitation won worldwide headlines.

On December 27, Flynn arranged for a full-page ad in The New York Times entitled “Irish Eyes Are Crying for Peace” co-signed by hundreds of leading Irish-American business and community leaders. The impact was immediate. “It set the tone,” Flynn remembers. “It created a sense that the Irish issue was one of great concern to leaders all over America.”

It was followed a few weeks later by another advertisement in The New York Times entitled, “Peace for Northern Ireland Is Within Their Grasp.” It was from the National Committee on American Foreign Policy and featured the five political leaders invited to the conference. The issue had suddenly become mainstream.

The Adams visa battle will go down in history as a seminal moment in Irish-American history. Against the odds, President Bill Clinton eventually sided with Flynn and the NCAFP and allowed Adams a 48-hour visa to come to America. In doing so he defied his own State and Justice Departments, FBI and CIA and key advisors including House Speaker Tom Foley.

Jack Farrell of the Boston Globe later wrote about the decision, “It was a case of classic Clinton, of a president who brooded and temporized and weighed the political ups and downs and then followed his heart down a risky path.”

For Flynn it was a majestic victory. After Adams arrived, Bill hosted a small party for him in a room at the Waldorf. The media world was full of images of Adams arriving in New York. Flynn himself felt utterly calm despite the whirlwind surrounding him.

The conference itself was a huge success, and the images of Gerry Adams speaking at the Waldorf Astoria with Flynn at his side were flashed worldwide. Also present was John Hume, SDLP leader and future Nobel Prize winner, and Lord John Alderdice leader of the Alliance Party, both of whom added to the history of the occasion.

In his remarks, Flynn promised that Ian Paisley and James Molyneaux, the two Unionist leaders who had refused the invitation, would be invited to come at a time more convenient to them. Within the next few weeks, both had agreed to come to New York and explain their positions. America was showing Ireland how peace could be made.

On March 17 that year the White House threw open its doors and invited leading Irish Americans from all over the country for a St. Patrick’s hooley. Hollywood celebrities like Michael Keaton, Paul Newman, Joanne Woodward and Richard Harris mixed with Senator Edward Kennedy, Senator George Mitchell and others. At about 11 o’clock President Clinton stood up to say a few words to the assembled 400 when cries of “bravo” rang out and a huge cheer arose. A Clinton staffer remarked that he knew then they had made the right decision on Adams.

Bill Flynn, the architect of much that had happened, was there that night, taking in the magnitude of the occasion, but also aware that much was still to be accomplished before the IRA ceasefire that was now on the horizon could be accomplished.

The next few months were full of back-and-forth negotiations with Sinn Féin by the American group. Assurances were sought and received, some of which remain private to this day.

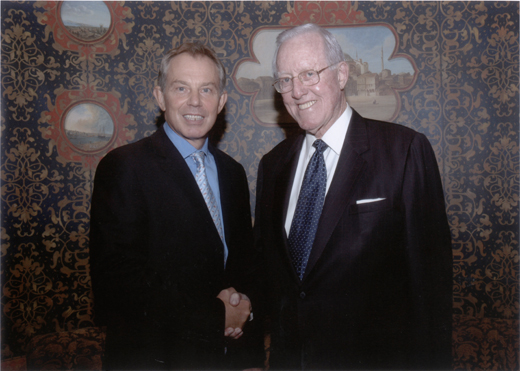

Flynn made several trips to Ireland, sounding out opinions in Dublin, London and Belfast, and forging friendships in all camps, including good relations with Sir Patrick Mayhew, the Northern Secretary of State, as well as, Sir John Stevens, the famous head of Scotland Yard.

On Thursday, August 25 the New Irish Agenda delegation was back in Dublin. The secret message had come from Sinn Féin that late August was a good time to come over to Ireland. The import was clear – the IRA was about to make a move.

They had a meeting in Dublin with Albert Reynolds and his Deputy Prime Minister Dick Spring. It was clear that a ceasefire was coming, but its length and whether any conditions were attached was not. Flynn himself believed the ceasefire would be open-ended and without conditions. “I felt we could trust Adams on that,” he says.

Amid huge media coverage, the New Irish Agenda group arrived in Belfast for their meeting with the Sinn Féin leadership. Once inside the door, Adams told them that the IRA was going to call a complete cessation. “It was one of my greatest moments,” Flynn remembers. “Against all the odds our group had helped achieve something historic and momentous.”

A few days later, Flynn was in Dublin when the historic announcement came down. The IRA had declared a complete cessation of operations.

“To me that IRA decision was the most natural thing in the world. I looked on it as another good business decision,” Flynn says.

“You know, in my business we celebrate great victories and then we’ll have a martini and we’ll go back to work. I felt awfully, awfully good about it, but the arguments were strongly in favor of this being the only reasonable solution.”

It was only when talking to his relatives in Northern Ireland that he realized the full import of what he had helped achieve.

Six weeks later on October 13, Bill Flynn was accorded the singular honor of being the only Catholic and American present when the Loyalist Combined Military Command met at Lord Carson’s old military compound in Belfast to announce the Loyalist ceasefire.

Flynn had been contacted by phone in America and told in coded language to come over. It was an incredible compliment to the Catholic son of a Northern Ireland father.

They invited him to meet them the night before and study the document they had prepared. “What I remember is that in the proposed ceasefire document Gusty Spence and David Ervine had apologized for the harm Loyalists had done over the years. And I remember urging them that they not take that apology out of the statement because it would mean so much to so many of the people of the North and, thus, help make the settlement come more quickly. We went over the statement word for word. The next day Gusty Spence told me, ‘Bill, whatever you do, should there be any cameras around, don’t get yourself in the picture.” So I sat in an anteroom with a former commander of the Combined Military Command and listened as Gusty Spence, to his great credit, read clearly and forthrightly, the order of ceasefire to all of the Loyalist forces. I was very pleased that they had invited me there. It was one of my proudest moments.”

In the years that followed, throughout breakdowns in the ceasefire, new IRA and Loyalist violence, roadblocks in the peace process, and presidential visits to Northern Ireland, Bill Flynn remained a key figure.

He ensured that every party, from whatever background, had a forum in America if they wanted to speak. On numerous occasions he personally flew to Northern Ireland to try and help when negotiations hit a snag. A measure of the man is that the British government, Loyalist leaders and nationalists and Republicans all considered him an honest broker when problems arose.

Throughout it all he remained true to his convictions that peace would find a way. He believes the Downing Street Declaration, the first document signed by Albert Reynolds and John Major in December 1993 remains the touchstone of the peace process. It affirmed the right of the people of Northern Ireland to self-determination, and that the province would be reunited with the Republic of Ireland if and only if a majority of the people was in favor of such a move.

It included for the first time in the history of Anglo-Irish relationships, as part of the prospective of the so-called Irish dimension, the principle that the people of the island of Ireland, North and South, had the exclusive right to solve the issues between North and South by mutual consent. The joint declaration also pledged the governments to seek a peaceful constitutional settlement, and promised that parties linked with paramilitaries (such as Sinn Féin and Loyalists) could take part in the talks, so long as they abandoned violence.

“It truly was the cornerstone for the entire process and you can draw a line from there through the Good Friday Agreement to the St. Andrews Agreement which brought about the power sharing government of today,” says Flynn.

The North’s troubles are likely coming to an end because of this agreement. Bill Flynn is one man who played an indispensable part. His father would be very proud. ♦

Leave a Reply