An Irish saying has it that “A dinner is not a dinner at all but only an excuse for one if it does not contain a plate of meat.” It’s a good bet that America’s penchant for “meat and potatoes” was cultivated by the immigrants who flocked here from Ireland, where meals built around meat have a long history.

Tracing the tradition requires journeying back to the days of the High Kings, when a chieftain’s wealth was determined by his cattle holdings. Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Cattle Raid of Cooley), the early 12th century epic in the Ulster Cycle of hero tales, recounts how a war erupted over the theft of a bull. Mebh, queen of Connaught, lost a dispute with her husband Ailill over who was wealthier because his herd contained a fine white bull and hers, alas, did not. Vowing to best him, she set out to steal Ulster’s even finer brown bull. Despite the fact that Mebh’s army was slaughtered by the Ulstermen, she succeeded. When Mebh returned to Connaught, her brown bull defeated Ailill’s white animal and peace was restored to the royal household.

Long ago, the vast majority of animals in Ireland’s herds were dairy cows rather than bulls. Beef came from unwanted bull calves, cows past milk-giving years, and animals that died accidentally. Dairy cows were more prized because they provided a constant and virtually free supply of milk, butter, and cheese.

The importance of dairy cows is illustrated in Odhar Chiarain (St Ciaran’s Cow), which appears in the 12th-century Leabhar na hUidre (Book of the Dun Cow). When the saint left home to study with St. Finian, his parents refused to give him one of their precious milk-cows. Trusting God to provide a miracle, Ciaran blessed a dun-colored cow in his father’s herd and the animal followed him to the monastery Clonmacnoise where it provided enough milk to satisfy not only Ciaran but all the students at the school.

Many of the 7th and 8th-century Brehon Laws pertain to cattle. Records show that the king of Leinster delivered a hundred head of each kind of cattle to his Munster overlord. Tenant farmers paid their landholders an annual rent of one yearling and one two-year-old bullock. The rulings even stipulated which cuts were appropriate for each class: “the haunch for the king, bishop and literary scholar, a leg for the young chief, the heads for the charioteers and a steak for the queen.”

Cattle also served as financial barter exchanges. Culdee monks charged a yearly tuition and boarding fee of one calf, several hogs, three sacks of malt and a sack of wheat. If a student could recite his lessons well, the monks earned an additional payment of one milk-cow.

Irish beef has always been famed for its flavor, and the best was reserved for lords’ tables. The 9th century tale of Fled Bricrenn explains why the meat served at a lavish banquet was so succulent: “a lordly cow that is also seven years old, since it was a calf has eaten nothing but heather and twigs and fresh milk and herbs and meadow grass and corn [oats].”

Because there wasn’t enough fodder to support entire herds through the winter, weaker animals were slaughtered and the meat was preserved with salt. Since ‘corn’ originally meant any small particle, including salt, the process became known as “corning.” In the Brehon Laws corned beef was referred to as “winter food” while “summer food” meant cheeses and curds, also known as “whitemeats.” While many modern Irish immigrants say they never ate corned beef in Ireland, in the 11th century poem “Aislinge meic Conglinne” it is listed as a “delicious prodigious viand” that appears in the author’s dream of a land of milk and honey where he encountered “many wonderful provisions, pieces of every palatable food… perpetual joints of corned beef.”

With cattle having been the measure of personal wealth since prehistory, it was natural for cattle to evolve as a cornerstone of the national economy. Beginning in the 13th century, Ireland began trading beef and cattle offshore. By the mid-17th century so many live animals were being shipped to England that British farmers were suffering. To rectify the situation, Parliament passed the Cattle Acts of 1663 and 1666, placing a tariff on every animal brought into the country and eventually banning the importation of live Irish cattle entirely.

With barely a hiccup, the Irish Provision Trade was established to export two of the most traditional Irish cattle products: butter and corned beef. County Cork became one of the largest slaughtering and processing centers in the British Isles. By 1776, Cork City was shipping 109,052 barrels of corned beef and tons of butter throughout the British Empire, Europe and America, earning it the titles of the Slaughterhouse of Ireland and the Butter Capital of Europe. During the Napoleonic Wars of the early 19th century, the British Army’s primary provision was corned beef from Cork.

By the end of the 19th century, Ireland had become one of Europe’s most important suppliers of cattle, and cattle-farming remains one of Ireland’s major industries yet today. With Irish beef now being shipped round the world, millions can enjoy a proper “plate of meat” at dinnertime without waiting for a holiday celebration. Sláinte!

The Origins of the Pot Roast

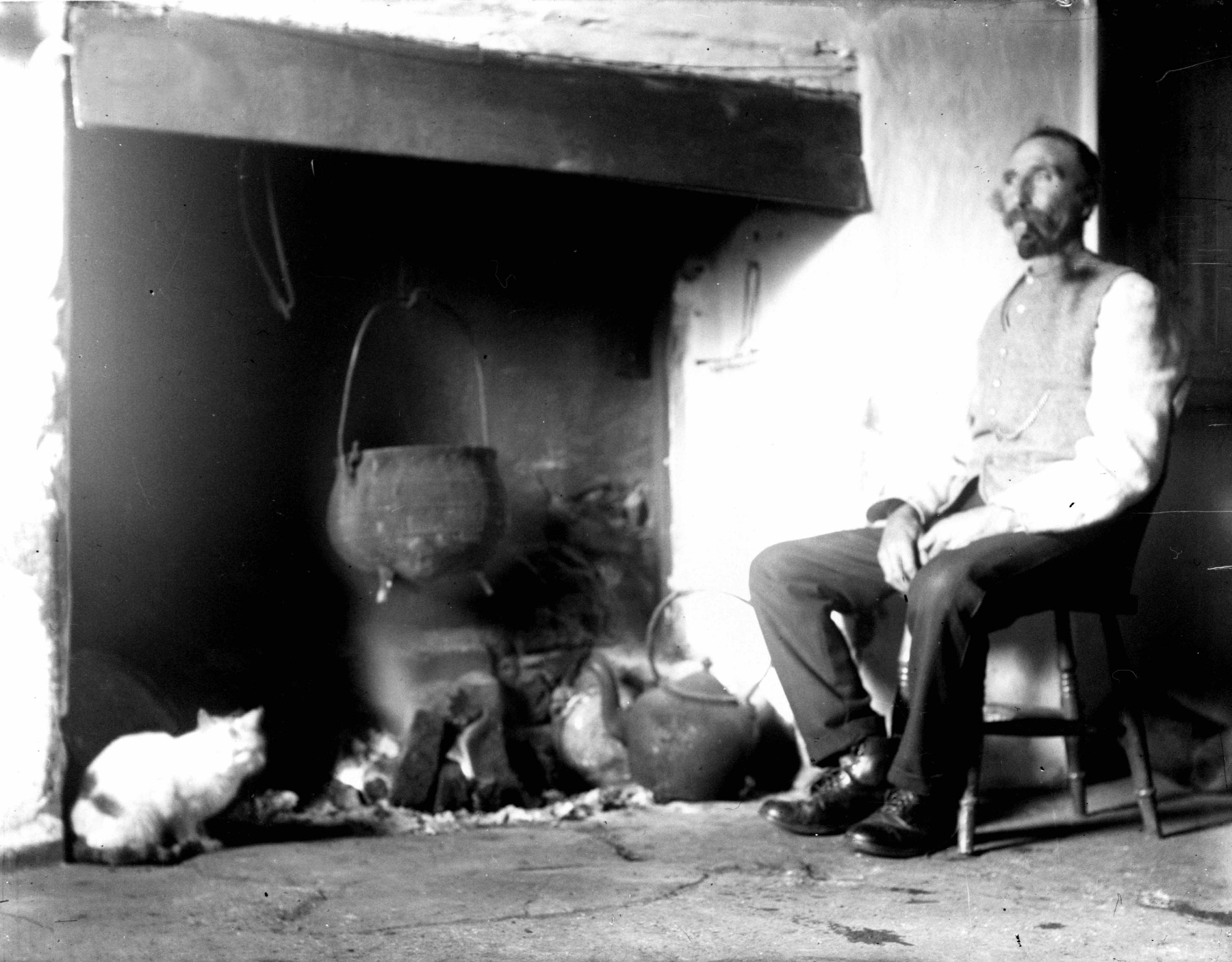

Until the latter half of the 20th century, an abundance of beef only graced the tables of the Irish gentry. The vast majority of the population subsisted on oatmeal, milk and potatoes, and when a household was fortunate enough to acquire some meat, ingenious cooks found ways to use every little piece. Irish stew (made with lamb or beef) is a prime example of culinary thrift. Cooked with carrots, onions and potatoes in a three-legged “bastable” iron pot with a curved lid that even the poorest homes possessed, it hung from a hook above glowing embers and simmered slowly for hours. The same pot, when stood on the hearth’s flagstone base amid the smoldering peat with its lid inverted and more coals piled on top, served as an oven. Sometimes onions and a bit of broth were added to the “pot roast” during cooking. In both cases, as the juices braised the meat, even the toughest cuts turned tender and flavorful. On those occasions when a whole haunch was spit-roasted on Sunday, leftover slices could be warmed in gravy and ladled over soda bread slabs for Monday dinner, chopped and covered with onions and mashed potatoes for a cottage pie on Tuesday, and if any bits still remained, ground up with carrots and onions and baked as roast beef hash on Wednesday!

RECIPES

Braised Steaks in Guinness (Classic Irish Recipes – Georgina Campbell)

4 round steaks

8 ounces sliced

mushrooms

1 large onion, peeled

and chopped roughly

2 medium carrots, sliced

in 1⁄4 inch rounds

8 ounces Guinness

1 sprig of thyme

salt and fresh ground black pepper

oil for frying

Preheat the oven to 350F. While the oven is heating, warm a little oil in a large frying pan and brown the steaks quickly on both sides. Remove steaks from the pan and set aside. Add a little more oil to the frying pan if necessary, saute the mushrooms and onion in oil for a few minutes until they begin to wilt, then spread the mixture and the sliced over vegetables of a medium ovenproof baking dish. Lay the steaks over the vegetables. Barely cover all with Guinness. Float the thyme sprig in the liquid and season the pan contents with salt and pepper. Cover the dish with a lid or tinfoil and braise in the oven for 1 – 1½ hours or until the meat is tender. Makes 4 servings.

Gaelic Steak Fit For A Queen (personal recipe)

1 8 – 12 ounce

sirloin steak, room temp.

salt and pepper

2 tbsp butter

2 tbsp Irish Whiskey

3 tbsp heavy cream

Season steak with salt and pepper. Put butter in a preheated black iron frying pan (don’t use a non-stick pan as you can’t get it hot enough!). When the butter foams, add the steak. Maintain the temperature and sear the steak on both sides to seal in the juices. Reduce heat and cook, turning only one time, to preferred rare, medium or well done. Pour whiskey over the steak and carefully set alight. When the flame dies down, remove steak to a warmed dish. Add cream to the pan juices, mix well, and boil to reduce a bit, then pour over the steak. Serve immediately. Makes 1 – 2 servings.

Cottage Pie (personal recipe)

3 cups minced leftover roast beef

2 large onions thinly sliced

1 to 2 cups roast beef gravy, warmed

4 cups mashed potatoes, warm

1 egg beaten with 2 tbsp milk

Preheat oven to 350F. Lightly butter a 2-quart casserole. Place minced roast beef on the bottom, cover with onion slices, then gravy. Spread mashed potatoes over all. Brush with egg/milk mixture. Bake for 1 hour or until potatoes are browned. Makes four servings. Note: For a “fancy” Cottage Pie, 1 cup cooked sliced carrots and 1 cup frozen peas can be mixed with the beef before placing it in the casserole. ♦

Leave a Reply