Why it’s time to reclaim the last days and figureheads of the old Gaelic world.

Stories matter, so here’s a good one. Four hundred and ten years ago this November the last two living Gaelic lords of Ulster arrived in Rome, uncertain of their welcome and feeling physically spent.

They were Rory O’Donnell former King of Tír Conaill, now the Earl of Tyrconnell, (with his brother Cathbharr) and Hugh O’Neill the Earl of Tyrone (with his son Hugh, the Baron of Dungannon).

If they felt like their world had collapsed they could be forgiven, because it had. Cruelly exiled a year earlier, their hasty departure from Ireland had signaled the final collapse of the old Gaelic order. One year later they arrived in Rome, after a perilous journey across Europe and the Alps that had been physically punishing for all of them.

We know that it was from the detailed account given in the Turas na dTaoiseach/the Departure of the Lords, the diary of the Flight of the Earls which was was kept by Tadhg Óg Ó Cianáin, a member of O’Neill’s retinue who journeyed with them from Rathmullen, County Donegal all the way to Rome.

The abrupt change in their fortunes must have broken their hearts. O’Neill was the same man who had once defeated Queen Elizabeth’s generals in Ulster, and who had effortlessly outmaneuvered the Earl of Essex, who led the biggest English army ever to Ireland to suppress his island-wide revolt.

But now it looked like their story had run out. All three members of O’Neill’s exalted company, minus the O’Neill himself, would be dead within the year.

I grew up on the shore of scenic Lough Swilly in County Donegal, the giant fjord that they had originally set sail from in 1607, and this June, four hundred and ten years later, I had an unexpected opportunity to visit Rome and go in search of O’Neill’s final resting place.

I felt called, to be honest. Growing up I had often wondered about them, O’Neill especially. Did he know he that was writing the last chapter of a great story, I wondered? Did he have the abiding sense of ending? Or did he hold out hope for a restoration, a return to power and to the old order?

The Annals of the Four Masters records O’Neill’s departure from Donegal: “That was a distinguished company for one ship, for it is most certain that the sea has not borne nor the wind wafted from Ireland in the latter times a party in any one ship more eminent, illustrious, and noble…” He was the among the first, and, as the Masters say, the most illustrious, of the centuries of Irish exiles that would follow. Millions of us have walked in his footsteps.

In Rome I booked rooms in Trastevere, the beautiful vine-covered neighborhood (which literally means “across the Tiber”) to the south of the Vatican. Maps on the internet had shown me I would be quite near to the church where O’Neill is buried, but on arrival I was astonished to discover I wasn’t just near it, I was literally at its foot. I had blindly thrown a dart at a map and hit bullseye.

Above my rooms lay a series of ancient steps that lead upward toward a steep hill, and at the top of that hill was the stately old church of San Pietro in Montorio. There are worse places to spend eternity. The elevated position catches the evening breezes and it looks out over the city’s fabled hills. A medieval tradition claims it was the site of Saint Peter’s crucifixion. It was twilight when I reached it.

Exile was such a fateful reversal for O’Neill. In Ireland he had been the chieftain of Tyrone and the most powerful lord in Ulster, but in Rome he was a political fugitive in need of aid, and a thorny political problem for the Vatican. The torturous political calculus of the period made him both a jewel and a pin, and that contradiction was never settled.

Researching the place before my visit I read that the poet John Keats had visited San Pietro in 1820 and the painter Giovanni Battista Lusieri had painted his view of Rome from the piazza on the Janiculum Hill around that time. Bellini had designed the side chapel. Looking out from my vantage point on the little hill I realized instantly that the view has hardly changed. Rome really is the eternal city.

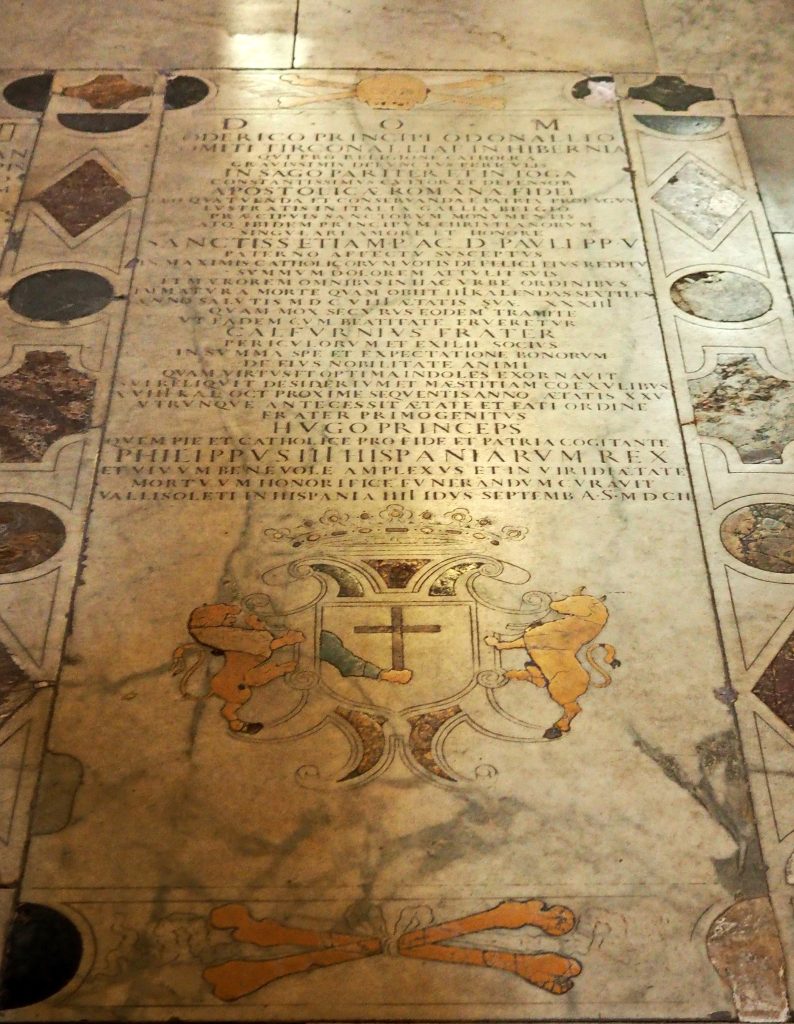

Impressive as all of this was I was only there to meet an Irishman, the last High King of Ireland, who is buried inside the San Pietro Chapel, near the altar. That’s his ossuary there on the left of this picture.

It’s a quiet place, fittingly sombre. It’s also a beautiful and antique place, and it was an easy matter to travel back the centuries to the time he would have known the place himself. After his departure from Ireland the Plantation began in earnest. It’s said that he maintained hope of a return to Ireland, but political events made it impossible. He eventually died in Rome on July 20, 1616.

The setting sun fell across the slab on the church floor as I viewed it. It was inscribed D.O.M. HUGONIS PRINCIPIS ONELLI OSSA (“To God the Best and the Greatest. The bones of Prince Hugh O’Neill”).

Looking at it, I realized something else had been driving me that I hadn’t been aware of until that moment. I deeply wished, I realized, that I could have one good look at him, but how he was whilst he was alive, speaking to him in both Irish and English, and also to his companions, including Hugh.

He was the last of the Mohicans, the O’Neill. A living link to an unbroken Gaelic lineage that stretched back into antiquity. He was deeply rooted in his land and his traditions. He was one of the last truly whole examples of a Gaelic man. It moved me just to be in his vicinity, four centuries later.

Looking around I also realized that I have never read of a single official Irish commemoration that has been held there to acknowledge the last chapter of his epic life. In fact, I can count on one hand the number of Irish people who have ever even asked me about him.

I know that Cardinal Tomás Ó Fiaich replaced his original ossuary stone in the 1980’s. I know that Irish scholars and individuals have made pilgrimages here over many decades, my own family members included. But we haven’t marked this final chapter, we haven’t given him the national wake and send off that he richly deserves.

I think we should. I think we should remember O’Neill’s epic journey and his great loss, which was our own great loss, and the start of many further ones. I think we could commemorate him now without stirring the wrath of the English, which was the fear during his own time.

And why should we commemorate him? Because the arrows that went up with the Normans came down with O’Neill, because he lived and embodied a fateful change in our history that we should honor and never forget.

Rome has preserved his remains for us but Ireland should preserve his memory. His story, as I wrote at the outset, matters profoundly. He stands at both the end and the beginning of a great shift in Irish history, and one way to come to terms with that lasting legacy is to commemorate what happened, to whom it happened, and for what it has made of us.

Rome is a beautiful and complex city, with so many eras clamoring for a hearing that we can forgive the locals if they sometimes shout. Most Romans I spoke to were unaware the very last Gaelic lord of Ulster was buried in their midst, at the center of one of their most beautiful neighborhoods, in fact.

We should change that, for them and for us. We should restore a part of what was sundered, we should publicly commemorate his final resting place, reclaim his story, and welcome his memory home at last. It’s time. ♦

I agree. Hugh O’Neill and Hugh O’Donnell should be remembered and honored for trying to uphold Gaelic Ireland.

A great article Cahir. Thanks.

Our Community Group ,Rathmullan The Way Forward would be very happy to welcome all interested parties to Rathmullan in County Donegal to celebrate Our History and Heritage and commemorate The Flight of The Earls from Rathmullan in 1607..

I can be contacted on mimcglynn@eircom.net.

Michael Mc Glynn.

Beautifully written article. Thanks.

Your article on Hugh O’Neill was excellent. Your articles remind me of my own trip through Latin America from which I recently published a book. “Irish Immigration to Latin America,” as well as my 3 month trip through the U.S, and a similar one through Europe. It’s a pity that the Irish only think of Immigration to the U.S. and England with nothing about Irish Colonies in

Cuba, Puerto Rico, 2 in Mexico, 3 in Brazil, 2 in Peru, 1 in Ecuador, a whole section in Uruguay, at least 1 in Chile, and several large ones in Argentina where I spent the most time.

It’s a pity that the slabs are now covered in carpet and they wouldn’t move it back when we asked to see the tombs.

Thank you for this . I am a very close descendent of Hugh /Conn and all O’Neills ( Ui Niall,Tyronne,Fews etc T ll the points where O’Neills connect) Conn who died in Rome was my Great Great x many Grand father, I live in NZ and there is a whole line of us here which goes to Lisbon and Cork. Obviously I am very proud of this family and we must do everything we can to preserve their memory.

Great article, Cahir! I, too, have fond memories of growing up around Lough Swilly. I propose that advocates for preserving this overlooked history consider staging Brian Friel’s “MAKING HISTORY” in this hallowed space. The play artfully captures (albeit somewhat fictionally) the tale of O’Neill and O’Donnell and their heartbreaking departure from Rathmullan. Following O’Neill’s exile in Rome, the play skillfully portrays his time there and eventual death. You tell the rest of the story by enshrining his final resting place in the church of San Pietro. Appreciate your insightful article!