In late 1990s baseball, home runs were everywhere. The balls were allegedly juiced. The sluggers were definitely juiced. Players who had been lanky rookies would later display cartoon-sized muscles, thanks to a regimen of syringes in the posterior. Even hitters of mediocre power were expected to belt 15 home runs per season. About one century earlier, however, 15 round-trippers could lead the whole league.

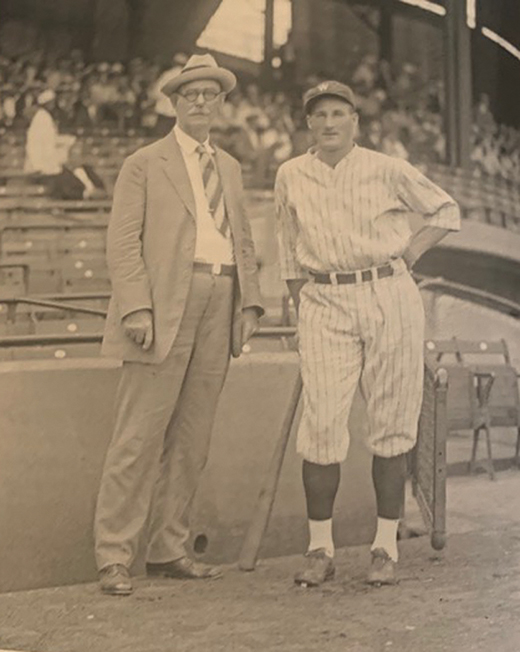

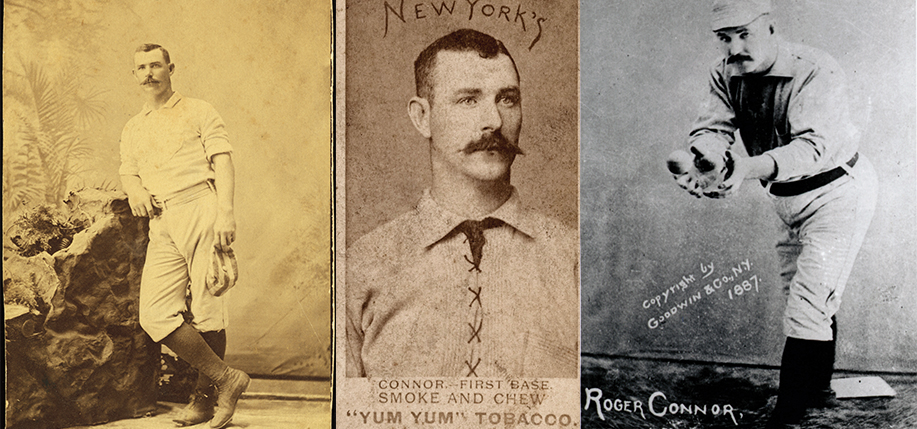

In that era of hard-earned homers, the mightiest power-hitter was Roger Connor. A broad-shouldered 6-foot-3-inch stud with a handlebar mustache, Connor and his chiseled 220 pounds looked the part of a slugger.

He was born in Waterbury, Connecticut, on July 1, 1857. One of 11 children (two of whom did not survive childhood), he grew up in the city’s Irish neighborhood, known as the Abrigador district. His father, Mortimer Connor, came from Tralee, County Kerry. At age 24, he arrived in New York City and found employment in a Waterbury brass mill. Not long after, he married Catherine Sullivan (also from County Kerry).

Roger left school at a young age and worked alongside his father. However, his work ethic became less consistent in his early teens as he began spending much of his time playing baseball.

Connor’s father “had no sympathy for his eldest son’s frivolous fixation on a game,” and the young ballplayer received “harsh retribution” for his pastime, as related by Roy Kerr’s Roger Connor: Home Run King of 19th Century Baseball.

Things became so problematic that, at age 14, Connor left home for the baseball bastion of New York, where he worked odd jobs and tried to find any team that would have him. But no one was interested in Roger Connor – not yet.

At age 17, he returned home to Waterbury. Undoubtedly, he must’ve been concerned about his father’s reaction. But this concern was unfounded, because, during his absence, his father had died.

In 1876, at age 18, Connor found a semi-pro baseball team, the Waterbury Monitors, that had use for his services. Two years later, he played for the Holyoke Shamrocks, where his power-hitting soon earned him a major league contract with the Troy Trojans. He made his big-league debut on May 1, 1880.

His batting average was a superb .332 for his rookie year. But his defense at third base was woeful; in 83 games, he made 60 errors. He was moved across the diamond to first base for the 1881 season. That year, his fielding improved, but his hitting declined somewhat.

Off the field, he married Angeline Mayer in 1881. She was a seamstress in a Troy shirt factory that made customized uniforms for Connor (the existing Trojan uniforms were not large enough for him).

In 1882, his third season, Connor was back hitting at a very high level, with a .330 batting average. The ensuing year, he joined the New York Gothams (who later became the New York Giants, the primary team of his career) and hit .357, second-best in the whole league.

In 1885, Connor had perhaps the best season of his career, batting .371. Also, he was establishing himself as one of the league’s best defensive first basemen. Additionally, he was proving himself a base stealer, a rare talent for a man of his size.

In 1887, he belted a career-high 17 home runs. But this successful year was marred by personal tragedy: Connor’s daughter, Lulu, died of dysentery shortly before her first birthday. He regarded her early death as divine punishment for his having married a non-Catholic (on that note, his wife would soon convert to Catholicism). The couple later adopted a girl, Cecelia, from a New York City orphanage.

In 1888 and 1889, Connor played a leading role on two New York Giants championship teams. In 1890, he posted a league-leading 14 home runs and was statistically the league’s best-fielding first baseman. He continued to put up solid numbers in the early 1890s. However, by 1894, Connor – who was approaching his late 30s – began to see his playing time reduced. So he switched teams, joining the St. Louis Browns. This team performed poorly, but Connor put up good personal statistics.

In 1896, he had the position of player manager for the Browns. As a player, he was fine. But his reserved personality was not conducive to leading a baseball team, and he resigned as manager mid-year, after a 15-game losing streak.

The 1897 season would be Connor’s last. He played only 22 games and struggled both at the plate and on the field.

For his major league career, he batted .316 and had 2,467 hits, including 441 doubles, 233 triples, and 138 home runs (a record that stood for 23 years, until someone named Ruth came along). Also, during his 17-plus major league seasons, the soft-spoken and gentlemanly Connor was never once ejected from the game by an umpire.

Not long after returning to his family home in Waterbury, Connor joined the local team in Connecticut’s newly established minor leagues. He held positions as player manager and even player owner before selling his club and retiring from pro baseball at age 46.

Over the ensuing years, Connor was enjoying a comfortable way of life, including winters in Florida, until in 1926 a mammoth Miami hurricane devoured his real estate investments. He and Angeline were forced to share a home with their daughter’s family.

Angeline died of a heart attack on St. Patrick’s Day, 1928. Not long after her passing, Connor’s own health began to decline: he would suffer cancer of the larynx, the removal of much of his voice box, prostate cancer, and sepsis from a prostate operation, along with heart disease.

He died on January 4, 1931, at age 73, and was buried alongside his wife in an unmarked Waterbury grave. The Great Depression was underway, and his loved ones lacked enough money to afford a proper tribute.

The strapping slugger who had inspired so many nicknames (such as: “Gentleman of the Diamond,” “Giant of the [New York] Giants,” “King of First Basemen,” “Squire of Waterbury”) went largely forgotten for several decades after his death.

Connor’s name was retrieved from obscurity in 1974, the year that Hank Aaron hit his record-breaking 715th career home run. The website for the Society for American Baseball Research relates how people began to wonder: “If Aaron had just broken Babe Ruth’s career home-run record, whose record had Ruth broken? The answer to that question shined the spotlight on long-neglected Roger Connor.”

In 1976, Connor was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y. Yet despite that recognition, his grave remained unmarked until a group of local baseball fans paid for a headstone.

This belated tribute came in 2001, the same year that Barry Bonds and his suspiciously transformed physique hit an all-time single-season record of 73 home runs. Such a lofty number is more than four times the career-high 17 home runs hit by Connor – an overshadowed titan of an untainted, long-bygone era. ♦

Great story . Loved the historical perspective of an Irishman achieving such success in America’s great game. And never thrown out of a game! A true sportsman.

I’m a SF Giants fan and today our announcer, Jon Miller, explained how our team’s name “Giants” was due to Roger Connor who was 6’3”! I googled him and wow! What a a life he led! One of his nicknames was “Giant” and he was so impressive, the team he played on, NY Gothams, changed their name to the NY Giants! I always assumed the NY Giants were named after the city’s tall buildings! Anyway, I loved learning about him and especially about his personal life, how he was buried during the Great Depression in an unmarked grave, (no family members could afford a headstone,) and how many years later fans donated $ to get a proper gravestone for him. Just a great story about a great man and ballplayer! ????????????⚾️????

PS: I just posted a comment, but wanted to add that I’m Irish, too, so I felt akin to Roger Connor! ????????????????

Great story and read. Perfect for Irish-America at this time of year!

Oh wow what an amazing story….. I am thricely interested as I started reading this, only to discover that Roger’s father Mortimer was from Tralee in Country Kerry and that’s where I am from too.

Catherine Sullivan , Roger’s mother is also from County Kerry and she has the same Surname as me so there is a possibility that we may even be connected. I will have to do some research to find out . Thank you for this fantastic read!