History speaks of migration waves that flow across land and sea and create epochal change. This description can obscure the smaller, often heroic journeys of daring individuals who establish new communities and identities for themselves and for posterity.

The poignant documentary ‘An Gorta Mór: Passage to India’ (also known as Boys from Vepery), written by Ian Michael and directed by Fokiya Akhtar, tells the migration story of one such outlier, John Footman, who, as a 21-year-old in 1847 escaped famine-ravaged Clonakilty, County Cork, for India. John eventually settled in Madras (now Chennai) and created his own Irish-Indian family. The story of John Footman as told in the film is also the personal history of the writer’s great-great-great-grandfather. One hundred and seventy years later Ian Michael journeys to Ireland to reflect on the meaning of his Irish-Indian heritage.

During the Great Hunger, when Ireland lost a quarter of its population to death and migration, millions braved the seas to seek a better life. Yet John was among the few Irish nationals to travel as far as India and begin a unique Irish diaspora there.

He was born in January 1826. Church records show that his father, also named John, and his wife Joanna Collins baptized their newborn in the Catholic parish of Ardfield and Rathbarry. The Collins and Footman families hailed from the villages surrounding Castle Freke, an ancient Norse stronghold that is owned today by Stephen Evans-Freke, a retired Wall Street investment banker who is rebuilding the castle once in his family’s possession.

Family lore has it that the name Footman is derived from the job that early members of the family held at the castle when not working the land. Also, Michael boasts, with the help of Irish genealogists, that John’s wife Joanna came from the same area in County Cork as her family’s namesake, Michael Collins, Ireland’s revolutionary hero.

John was just 19 when the Great Hunger struck Ireland in 1845. Two years later in the Famine’s darkest hour, he recognized the extreme adversity his family faced. Reasoning that his best chances lay elsewhere. He left his parents and five siblings and sailed from Queenstown (now Cobh), which in time became the point of departure for 2.5 million of the six million Irish who emigrated to North America between 1848 and 1950. Unlike his fellow travelers, John sailed first to England and from Chatham dockyards boarded the Kent clipper ship to India by way of the Cape of Good Hope. On board were 227 other passengers, including 213 men, 13 women, and 1 child. The journey to Marina Beach in Madras on the Bay of Bengal took about four months.

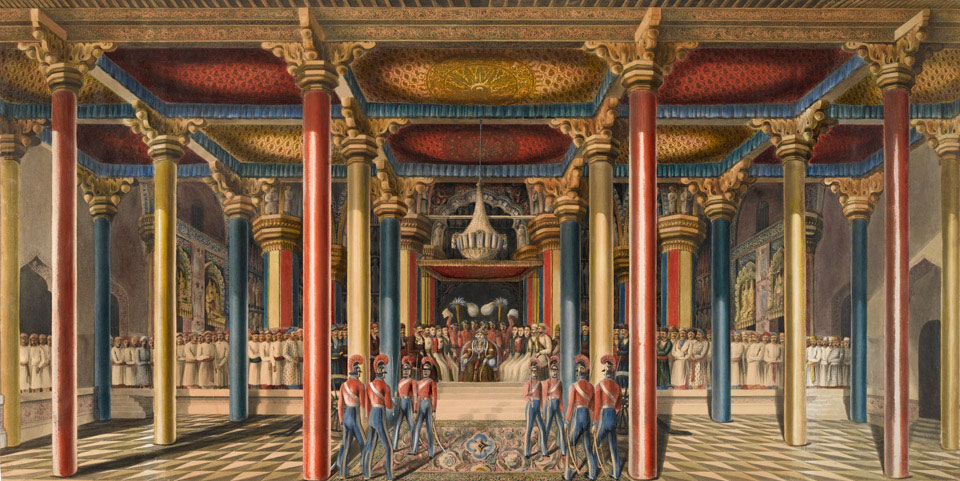

All the young men, as seen on the ship’s register, were mostly Irish, recruited and bound for Madras to join the East India Company in the British Infantry division known as the Madras Presidency. At the time, Madras had a population of 400,000. The East India Company, a privately owned trading concern, had been gaining financial and political power in India since the seventeenth century. By the time of Footman’s arrival, Britain’s control over India was complete: English governors headed each province and were responsible to the British Parliament.

Six years after his arrival, by then an officer in the Regiment, John married Matilda, an Indian woman from Mangalore (now Mangaluru), a city in South India. They settled in Vepery, one of the oldest neighborhoods in Madras developed during the British settlement. It was there they raised six children: Mary, Michael (named after John’s elder brother Michael, who lived in the farmland of Dundeady until the ripe age of 82), George, Patrick, Christopher, and Evangeline.

Like all Irish and Anglo Indians, the Footman’s kept to themselves, mostly interacting with members of the Irish-Indian and Anglo-Indian communities. The only Indians they interacted with were those with whom they worked. They did not fully embrace Indian culture, and the women of the family rarely if ever wore Indian clothes.

Life for a soldier could not have been easy. Beginning in May 1857 and lasting until July of 1859, the Indian Rebellion, commonly known as the Sepoy Mutiny, fought the rule of the East India Company. The rebellion soon escalated into mutinies and civilian rebellions in the upper Gangetic plain and central India.

The British Empire was not, as historian Niall Ferguson would like us to believe, “a benevolent agency imposing free markets, the rule of law, investor protections and relative incorrupt government on roughly a quarter of the world”. Rather, in the aftermath of Sepoy, “British security forces deployed ever-intensifying forms of systematic violence that made empire look like a recurring conquest state,” writes Harvard professor Caroline Elkins in her new book, Legacy of Violence: A History of the British Empire. Britain, according to Pulitzer Prize winner Elkins, was “[A]n Empire built on the backs of countless enslaved and colonized peoples across Britain’s empire – an empire that, in its heyday, covered over a quarter of the world’s landmass and claimed 700 million people as its subjects.”

In 1877, the year that Queen Victoria was anointed Empress of India by the British Parliament, while still serving in the British Army at age 51, John Footman passed away. On his death certificate, “disease of the heart” was given as the cause of his death.

Ian Michael has fond memories as a 12-year-old listening to stories told by John’s granddaughter, Agnes Footman, his great grandmother who lived in Hyderabad in the northern part of South India.

“Sipping grog in an old-style British home at Hyderabad’s Sarojini Devi Road, Agnes would tell of her great-grandfather’s family of fighters and revolutionaries who migrated to India during the Great Famine. She would go on for hours, talking about the valor and lineage of these Irishmen. Ian recalls that, as a child, the distinguishing characteristic of his family was their accent — an unusual hybrid of Irish and Indian.

In later years, Michael gleaned family history from Agnes’ daughter-in-law, his grandmother, the former Joyce Curran, who entrusted to him family documents that he used for research, others came from Vivian’s cousin, Juin Burnett, and Agnes’ nephew Dudley Footman. From Joyce, who was born an Irish Indian in Bombay, he learned that most Irish Indians worked on India’s vast network of railways engineered by the British. He tells: “My grandmother Joyce Curran, wife of Vivian Francis, was the Station Master of Nampally station in the 1960s and ’70s. Her brothers, the Currans, were divers at the Mazagaon docks in Bombay.”

Over the generations, the Footman clan grew to more than 500 across India. Later, beginning in the 1960s, the family roots expanded to Melbourne and England, where many emigrated after Indian independence. A highlight throughout the film is the gathering of small groups of descendants of the disparate family recounting their personal histories with Michael from Melbourne to Clonakilty.

John Footman embodied diaspora, which means scattered population. Today, there are seven generations of Footman in this Irish-Indian family residing in India, Australia, North America, and England. Through his work, on both sides of the world, Ian Michael is helping his Irish-Indian family fully embrace the realization that Ireland, too, is their home and assure his Irish relatives in County Cork that they will receive a warm welcome in India. ♦

An Gorta Mór: Passage to India premieres Sunday, June 19, 2022 at 10:00 am ET, 3:00 pm in Ireland, and 19:30 in India and may be viewed on the Strokestown Park website.

The article is enlightening. Of the 82 countries I’ve been to, India is the only major country that I have not

been to. When I was in Pakistan for about 5 weeks getting paid for doing nothing, I tried to go to India but political problems would not allow same at that point in time. The same happened when I spent time in what used to be called East Pakistan.

The article is very educational after perusal and cogitation, especially when we usually only hear about emigration to the U.S, Canada, and Britain, during Famine times.

Perhaps a read of my book: “Irish Immigration to Latin American” where I spent some time would be likewise.

It elucidates in detail on Irish Emigration to South & Central America.

why is it they are talking all about the footmans my grandfather patrick curran also from cobh cork one of his daughters was adelaide curran she married harold taylor they all lived in lallaguda secunderabad they worked on the railway would like to know more about the curran family my uncle veron curran worked as a deep sea diver in bombay please any one who knows the curran boys two brother william and patrick or thomas they both worked for the railway in secunderabad thank you patricia gilgan from sligo ireland

Hi Patricia,

I am Vernon Curran’s grand nephew, my Nana Joyce was his sister.

Please connect with me.

Ian

thanks for answering me i met Vernon when i was a young child all i can remember is my mother asked him would he look after me at the time i didn’t know my mum was very ill and she knew her time had come i was 15 yrs old when she died i do know my mother gave him documents of me i don’t know what he did with it. i ended up living with my sister Shirley in Bombay, then she brought me to England. Now i live in Ireland my husband came from county Sligo sadly he passed away in 1995. I would love to find out more of Verons father what year he was born and what year he went to Secunderabad you see his father and his brother both ended up in Secunderabad . Please keep in touch and if you know where in Queenlands now Cobh i will be able to go to Cobh and see where the two brothers come from god bless patricia

i didnt get a reply

Hi my name is jude dominic curran s/o Patrick Daniel curran s/o Micheal daniel curran s/o patrick _ curran

Hi I’m jude curran son of patrick curran grand father Micheal curran great grand father patrick curran irish

HI JUDE CAN YOU GIVE ME MORE INFORMATION ABOUT YOURSELF AND ALSO WHERE YOU LIVE AND IF YOUR FATHER OR GRAND FATHER LIVED IN INDIA IN SECUNDERABAD HOPING TO HEAR FROM YOU PATRICIA BY THE WAY I LIVE IN SLIGO THANKS PATRICIA

Hello Patricia, hope all well. I may be in Ireland around August-September. It would be good to catch up if you are free. I may have some pictures of the Curran’s. If you can provide me your email I can share. Regards, Ian

would love to meet up my email is beanknock@hotmail.com

Hi Patricia,

Vernon’s father’s name is James Curran, he is my great-grand pa. He and his son Eric and him moved to Secunderabad to live with Joyce Curran, my grand-ma, happens to be James’s daughter and Eric’s elder sister.

Are you a Curran? What’s your Dad’s name? If you provide me your email, I could email you documents I have e.g., Curran family, James marriage certificate etc.

no i am not a curran but my mother was her name was adelaide curran and lived in secunderabadi would love you to sharethe curran family

Hello! My name is Samuel Sudhakar and I live in Secunderabad. I am deeply interested the pre-British era history of the city and collect as many stories, images that I can lay my hands on. I would be keen to know if any of you has some pictures of your family, friends or just plain city images back then. Thanks!

I will try and get you some Samuel. Where did you live in Secunderabad?

its great to know some one in the curran family