In the half-century that New York’s Ellis Island served as a receiving station, more than 16 million immigrants passed through its doors. Ruth Ford talks to Irish immigrants about what they experienced.

It is September, and cool inside the brick passageway connecting Ellis Island’s registration hall with the moldering buildings that ring the island grasses. Outside, tourists stroll the pier in front of the registration hall, their voices and the cries of the seagulls muted by the passageway’s thick walls and limestone floor. Peering through a keyhole, I can just make out a row of desks tagged and stacked beyond the padlocked doors. The few shafts of sunlight invading the gloom reveal sharp edges of the heavy wood furniture. I squint and refocus, trying to bring the darkened shapes into view. A sudden question pulls me back to the present.

“Do you believe in ghosts?” The impulse to dismiss the question fades when I face the speaker, a serious-faced young man wearing the olive green uniform of Park Service employees, my guide on my unofficial tour of the island. After a moment’s hesitation, I offer a tepid “maybe.” He shrugs. Some of the people who work on the island are convinced there are ghosts, he tells me. He gestures toward the room where the furniture lies stacked. “They leave notes for them when things go missing in there. There’s a lot of wood in that room. Ghosts are supposed to be attracted to wood.” I have no idea what to say to this, so he shrugs again and begins strolling up the corridor. Check your film when you get it developed, he says over his shoulder. “A lot of people have found a white haze on their photographs they can’t explain.” I watch him for a moment, then squint again through the wooden keyhole. In the darkened room the faint sunlight licks the edges of the shrouded furniture. “Nah,” I think to myself, “couldn’t be.”

Driving back and forth across the bridge connecting Liberty State Park to Ellis Island this past fall, my disbelief in ghosts begins to fade as my wheels find the familiar grooves in the metal bridge. Tucked away in the library, listening to the taped interviews of immigrants who passed through the island, I begin to wonder at silences gathering at the edge of the stories — silences born not of too little memory, but so much. Like tunnels mined at a tide’s edge, the dug-up stories pool under the ebb of their silences, words dissolving in memory until one immutable fact remains — they endured.

“If I didn’t do it quick, I wouldn’t do it at all, so I just got it over with. I said I’m going, and I’ll try, see what it’s like. But when I was on Ellis Island — Dear God, was this the way it’s going to be always?” Bertha Devlin was 22 when she sailed to New York on the Cameronia in March of 1923, the stormy weather eclipsing for a short time the ache of separation from her family. Devlin came from Mindoran, in County Derry, the second child to emigrate to America, a fact that did not ease her departure for her mother. When the passage money arrived from her brother in America, Devlin’s mother hid it from her. “My sister told me one day that it came, so I kept after her until she gave it to me. She didn’t want me to leave,” Devlin said of her mother. It fell to her father then, to see her off. He traveled with her as far as the ferry that took her to the ship, and then returned home. “I never saw him again.”

The decision to emigrate was the only way out, Devlin told her interviewer in 1985. “We didn’t have anything to do in Ireland, there was no work, and you didn’t want to be poor all your life. You could have married an old farmer if you wanted to, and stay there for the rest of your life. I could have done that, but I wasn’t about to.”

“You grew up, turned 17 and 18 and went to America,” Theresa Fahy Minogue concurred with old-world matter-of-factness. Now 91 years old and living on Staten Island, Theresa was 17 when she left the family farm in County Mayo with her sister Eileen Marie. It was 1923, and the violence of Ireland’s civil war was stirring the edges of even the most secluded farmland, but Theresa and her sister saw past the dangers of traveling across the countryside to their ship in Queenstown — and all the way toward an aunt and a future that lay waiting in New York. Eventually, eight of the nine Fahy children emigrated; only Patrick, the eldest son, stayed on the family farm in Mayo.

Still woozy from a night of singing and dancing, Mary Ellen Smith sailed for New York in 1920 with the songs of her American wake still ringing in her ears. She was only 16. “We had a wonderful evening,” Smith recalled. “There was dancing and singing….We had a grand time.” She should have gone to bed, Smith wryly reflected. “I wrote to them afterward, and told them that they should have had that shindig the week before.” She came from farm country — Tarman, County Leitrim. In the thatched house where she grew up, the rooms were lit by lamps and steaming pots hung over an open fire in the kitchen. Each night they prayed the rosary. “My mother was very upset when I wanted to go,” Smith said. “But I felt there was a future for me here, and there wasn’t one for me in Ireland.”

Today, no more than 30 feet from the entrance to Ellis Island’s registration hall, a pile of luggage lies at the foot of the stairs to the great hall. Stained, cracked and weather-beaten, this display, more than any other, evokes a visceral sense of the labor of emigration — of the physical hauling of an old world toward a new world’s promise.

“I think there was about four of us in one bunk, in one little place, and, oh, God, I was sick. Everybody was sick. About the fourth day we got up on deck — it wasn’t too bad then, but I don’t ever want to remember anything about that old boat,” agonized Devlin. “One night I prayed to God it would go down because the waves were washing over it I was that sick. I didn’t care if it went down or not. And everybody was the same way.”

“The men traveled with the men, and the women traveled with the women, that’s just how it was,” Emanuel Steen remembers, now 90 years old and living in New Jersey. “It was four in a cabin. Two up and two down with a tiny wash basin, toilet was down the hall. It was very close quarters. I mean it was jammed. There must have been 2,000 people on that thing in third class.

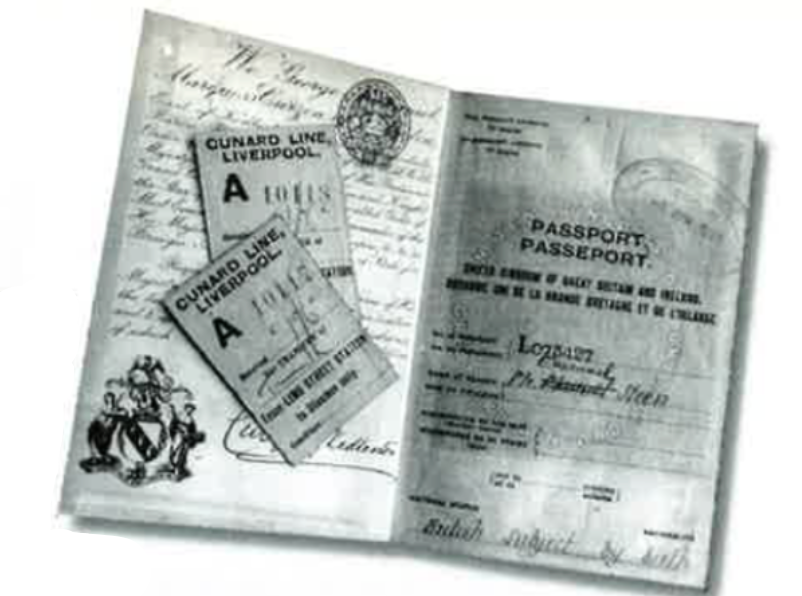

“All I had was the suit I wore. I think I had an extra handkerchief and a pair of socks. I also had my stamp collection…and a few family souvenirs. I didn’t fill the suitcase. I couldn’t. I didn’t have enough stuff to put in there.” Steen was 19 when he took the ferry from Dun Laoghaire to England, where he boarded the Caronia in Liverpool. His older sister Bertha went with him, sent by their uncle who was unimpressed by the young man with whom she had been keeping company.

Steen and his siblings grew up in a government flat long before their address off South Circular Road was converted into private homes, now among the most coveted real estate in Dublin. It was a crowded house, Steen remembered, with eight children and an uncle, who had escaped with Steen’s father from a Ukrainian pogrom in 1891.

“They hid out and took a ferry boat to Constantinople. They worked there for a short while, got a job aboard a merchant vessel as seamen, jumped ship in London and exactly how long they worked there I don’t know but eventually, a few years later, they came to Glasgow,” Steen recounted. His grandparents were massacred in the pogrom, he said.

“My mother’s parents were from a village near Warsaw. That’s a separate adventure in itself, because the refugees from Poland and from Eastern Europe walked across Europe to the port of Hamburg and bought passage on a ship they thought was headed for America.”

But it wasn’t, said Steen. “The captains of these illegitimate boats dumped the refugees on the east coast of Scotland during the night. They just dumped them and they said, `this is America,’ and they took off.” The Scottish government gave the refugees a cautious welcome, telling them they could stay as long as they didn’t become an economic burden. “Eventually, that’s how a large Jewish settlement ended up in Aberdeen, Edinburgh and Glasgow,” said Steen. His father and mother met and married in Glasgow, and later moved to Dublin. “We were poor people, but not dirt poor,” Steen remembers. “There are different levels of poverty, as I can see now. We were poor, but we ate.” On the other side of the ocean, America beckoned. At the age of 19, with $20 “to show financial independence” Steen and his sister set sail on the Caronia.

Manny and Bertha arrived in New York on August 1, a Wednesday, Steen believes. “I remember about six o’clock in the morning…the lookout said, `Land ahoy!’ Everybody rushed up on deck. We couldn’t see a goddamned thing,” he said. And then, there was New York, said Steen, coming out of the sea. “And the first thing you see [is] the Woolworth building. That was the highest building in the world at that time.”

When the Steens arrived in New York in 1925, Ellis Island was already a tiny city sitting on 27 acres of dirt, dirt excavated during the construction of the New York City subway system. More than 700 translators, inspectors, doctors, nurses, clerks, cooks, matrons and more worked on the island, feverishly trying to keep up with the flood of immigrants ferried daily from the steamships anchored in the harbor. The first experience of passing through the massive red-brick registration hall still haunts the memories of the immigrants.

“I remember getting into that hall and thinking, `I’m never going to get out of here,'” Mary McCreight Maddock recalled. The crash of the people and the noise and confusion were almost more than the 11-year-old could bear. She wanted to be back in Belfast, in her grandmother’s row house on 29 Ripple Street with its bay windows and plants. But that was not to be. When her aunt left to join her husband in America, Maddock went with her. For 10 days she shared a tiny stateroom on the Furnessia with her aunt and six-year-old cousin Violet, arriving on Ellis Island in January of 1909. The trio had one piece of luggage, a trunk packed with their shared belongings. Miserable, Maddock stayed close to her aunt in the registration hall, barely able to make sense of the confusion.

“You were tagged. Everybody was tagged. That was the first thing,” Steen remembered of his reception at Ellis Island. “They went through your baggage, they had to check your bags, and then they pushed you, they just pushed you. You know what I mean? They’d point, because they didn’t know whether you spoke English or not. They could have looked to see, I suppose, but they didn’t. Nobody asked me.” Worse, though, said Steen, was the physical that was to come.

“The doctors were seated at a long table with a basin full of potassium chloride, and you had to stand in front of them, and you had to reveal yourself,” he said. “They gave you what we used to call in the army a short-arm inspection. Right in front of everyone. It wasn’t private.”

It was awful, said Bertha Devlin. “Your clothes were all taken off, and your hair was looked into. If there was one nit in your hair, you had to have a shampoo. I didn’t, thank God.” Other immigrants weren’t so lucky. When a skin disease broke out on Anna Walsh’s ship, anyone who wasn’t a citizen couldn’t leave the ship. “They sent us to a place called Hoffman Island, and you had to go into a room and sit naked, and 1 nearly died of embarrassment.” She was 16 when this happened, said Walsh, and menstruating heavily. “The room had no ceiling, and they came in, and hosed us down. One nurse said, `you poor kid, this is awful.'” Sixty-four years later the relief is palpable in Walsh’s voice as she recounts being permitted to dress and rerum to her ship.

As the number of immigrants swelled at the close of World War I, Congress passed the first of two quotas in 1921, restricting entry to no more than 3 percent of any given nationality living in the U.S. at the time of the 1910 census. Two years later, annual immigration was limited to 2 percent of the nation’s population as of the 1890 census. The reluctance with which the Americans met the crowds of arrivals was also manifested in more stringent entry requirements: two medical exams were required, as well as a literacy test. Once again, the strictest enforcement fell on the passengers traveling third class.

Recalling his Ellis Island physical in a 1993 interview, Michael Jordan spoke derisively of the doctors examining him and his brother in 1924. “They said [Chris] had some kind of trouble with breathing, which was a farce. They said he got that from cigarettes. He never smoked in his life, and neither did I. And because of my traveling in the same bunk with him, they held me too,” said Jordan. “We were there for three or four days…At the end, we were released.” Afraid of the repercussions of a bad medical report, the brothers haunted the registration hall, declining to go outside lest their uncle coming to meet them failed to find them. “We were pretty green,” Jordan admitted. But what else were they to do? — failure to pass the physical meant rejection and a long voyage home.

Had the Irish doctor examining John Waters before Waters emigrated known of the Jordan brothers’ experience, no doubt he would have used their stories as a cautionary tale. As it was, he had plenty to say to the 20-year-old before Waters boarded the Lancastria out of Cork for America. “My wife [was] in the United States for four years. It’s a wonderful country, she liked it, but don’t get the idea that it is the land of milk and honey,” the doctor warned Waters. There are no streets paved with gold, he said. The doctor ticked off the requirements for success in America: “If you are lucky, and you’ve got your health, and if you work hard, and you are ambitious, you may make it. If you are unlucky and you don’t have your health, you are going to get in trouble.”

Whether it was good luck or good health, or both of these or none of them, Waters passed his physical in 1929, among the last of the thousands to pass through the island.

Patrick Shea had the ambition and the good health, he thought, but bad luck and a tramped up medical condition kept him from entering America in 1925, he said. “We were called up one by one, and my brother was behind me…They told me [that] I had a bad heart and bronchitis, and they gave me two weeks to live,” snorted Shea. “Nothing was wrong with my brother, but they gave him the same thing. And we never missed a meal or a dance or anything coming over on the boat.” Patrick Shea and his brother were detained on the island for 17 days, then returned to their ship, “like prisoners,” Shea said. Seven other Irishmen made the trip back to Ireland. Once in Queenstown, the men were examined again. As he expected, none of the doctors found anything wrong with the brothers.

The ordeal proved too frustrating for Patrick’s brother, who returned home to County Kilkenny. Patrick was undeterred. He emigrated again, this time to England, where he worked for three years as a laborer in Manchester. In 1928, he moved to Canada. One year later, he decided to try to emigrate to America again. It took medical affidavits cabled from Ireland and England to finally convince the officials to allow Shea to enter the country. Armed with his evidence testifying to his good health, Patrick Shea entered the United States through Canada in 1929, four years after his first attempt. He was 28.

For most Irish immigrants America became home. Elizabeth Rice Dalbey, who immigrated from Galway in her early 20s, summed up the conundrum who is Irish and what is home when she was interviewed by Ellis Island historians at the Cedar Manor nursing home in Ossining, New York in 1995. Dalbey, who turned 100 this past November, was asked whether she considered herself Irish or American. “American,” she answered immediately. The interviewer persisted. “What part of you is Irish?” he asked. “Every bit of me,” came the no-nonsense reply.

In 1954, after a debate that went on and off for almost two decades, Ellis Island was closed. In the more than half-century it served as a receiving station, more than 16 million immigrants passed through the island. In recognition of this fact, renovations were begun on the registration hall in late 1980s, citizens and government officials alike calling for a restoration of the registration hall to its former structural glory.

Today, far from the registration hall, the unrestored buildings on the edge of the island lie silent, their rooms and corridors choking beneath the weeds growing under doors and up through the high broken windows. In the mammoth kitchens, stove lids hang open beneath a ceiling shedding its asbestos-poisoned skin. Sunlight streams through a broken wall in the laundry, room, drying the heavy canvas rollers still wet from the last rain. In the contagious disease ward, a solitary chair sits in the middle of the cavernous room. A shade, unfurled, is cracked and brown.

Retrieving my film from the developer when my research was done, I riffled quickly through my photographs of the island, captured again by the eloquence of the slowly decaying buildings. Then I looked at them again, this time more carefully, disbelieving what I saw. Across the last photograph, a thin white haze curved from border to border, a serpentine blur that seemed to outline, almost, the shape of three figures. “Nah,” I thought to myself. “Couldn’t be.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the May/June 1997 of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply