Tap-dancing great Donald O’Connor talks to Kevin Lewis.

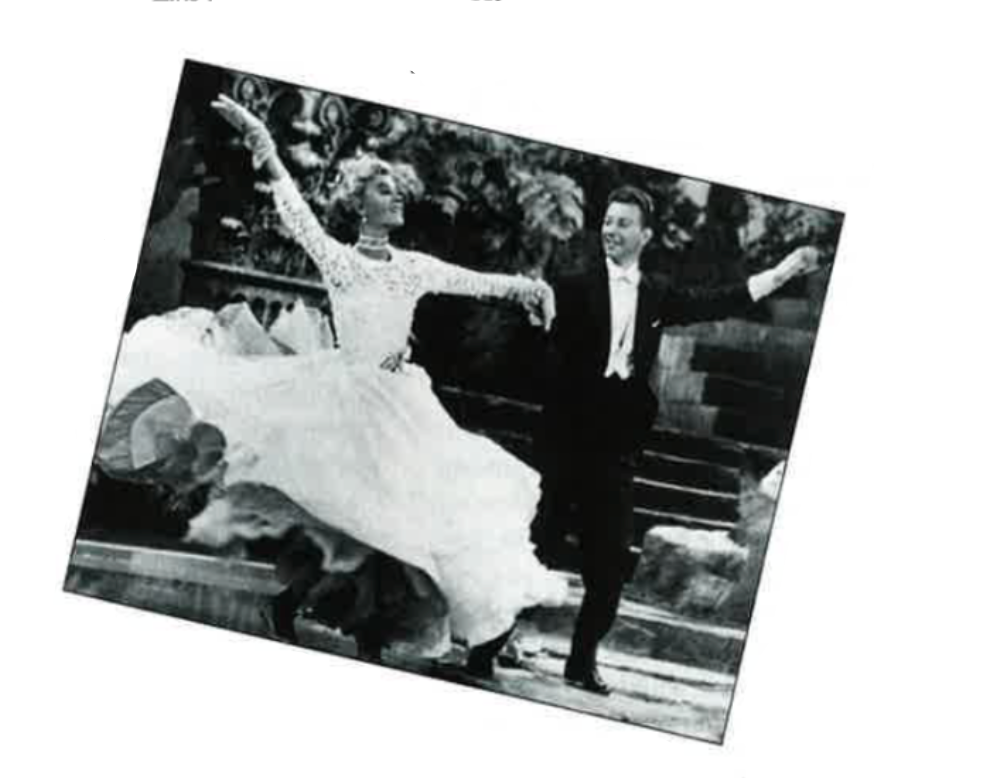

If living well is the best revenge, life must be sweet for dancer Donald O’Connor. In the Golden Age of Hollywood, O’Connor ranked only behind Gene Kelly and Fred Astaire because, with the exception of Singin’ in the Rain (1952), he was not showcased in a dazzling series of prestigious musicals. Rather, at a critical juncture in his career he was even paired with a talking mule. Donald O’Connor is a show business survivor who has worked continuously since the 1920s and still works 32 weeks a year, sometimes with his former co-star Debbie Reynolds. Currently he can be seen performing a show-stopping dance solo in the new Jack Lemmon-Walter Matthau film Out to Sea.

O’Connor was in New York in late May for twin tributes. First, he received the Flo-Bert Award at Tap Extravaganza ’97 from the New York Committee to Celebrate Tap at Town Hall in recognition of his matchless tap dancing. The award also recognized his promotion of scholarships in dance and a retirement home for aged and indigent dancers as president of the Professional Dancers Society. Then, in two nearly sold-out evenings at the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s Walter Reade Theater, O’Connor discussed his long movie career in the Capturing Choreography series.

O’Connor illustrates and defines the mainstream Irish American experience, characterized by practical business sense as opposed to the over-publicized dreamer. When the major movie stars were set adrift in the 1950s by the collapsing studio system, O’Connor had already secured his niche in the early television industry, winning a 1954 Emmy for his show the Colgate Comedy Hour. He made sure he would have work by becoming his own director on Here’s Donald, and was one of the earliest performers to join the Directors Guild of America.

O’Connor entered show business in the traditional Irish way, through vaudeville. Look beyond the razzle-dazzle, eccentric dancing and you can see pure Irish folkdance. O’Connor admits that for much of his early career he was a hoofer and danced from the waist down. When asked if he sees a connection between his dancing and that of current Irish dance troupes such as Riverdance, he replies “Riverdance is incredible. My God, that’s part of me and my background.”

O’Connor’s father John “Chuck” O’Connor emigrated from County Cork. “My father, when he worked on circuses as a kid, was a singer, a dancer, an acrobat, a trapeze artist, a clown, a comedian, and also a strong man.”

Also in the circus was Effie Irene Crane, who had run away from home when she was 12. She married Chuck when she was 13 and had her first child the following year, but continued to work as a tightrope walker, bareback rider and a dancer.

Donald David Dixon Ronald O’Connor, born in 1925, was her seventh child, and Effie had her own way of keeping an eye on her growing brood — The O’Connor Family act. O’Connor recalls, “As soon as they were born, they went right into the act. I was only three days old when I was next to mother on the piano bench, because it was the safest place for me.”

Donald never knew his father. Chuck died on stage of a heart attack when Donald was 13 months old. Donald recalls, “My father could do everything and so I grew up with this phantom character, hearing all these stories about all the things he could do, and so I tried to emulate him. He was 5’5″ and weighed 220 pounds. He was very light on his feet though: he was known as the Njinsky of acrobats. The height he could get was incredible.”

After Chuck died, Effie kept the act going with the help of her sons Billy and Jack, who taught Donald to dance and do acrobatics by the age of three.

Donald was signed to Paramount Pictures in 1938. His sassy singing of “Small Fry” with Bing Crosby in Sing You Sinners was his first triumph. He continued with the family act until he was signed by Universal Studios for a series of teenage musicals which capitalized on the jitterbug craze. Surprisingly, O’Connor never took a formal dance lesson until he was fifteen years old, well into his starting career, and credits Universal choreographer Louis Da Pron with turning him into a complete dancer by teaching him to use his upper body and his arms.

O’Connor co-starred in the film There’s No Business Like Show Business (1954). He recalls that making the film was traumatic because of the volatile personalities involved, including Ethel Merman and Marilyn Monroe. Monroe was fearful that her jealous husband, Joe DiMaggio, was having her watched by detectives. On the day that she and O’Connor were to film a kiss, both were scared stiff. His trepidation at kissing Marilyn Monroe was not helped by the over 1,000 onlookers watching him. “I was so nervous that I couldn’t find her mouth.”

To complicate matters on the set, Dan Dailey, who was playing O’Connor’s father, was dating O’Connor’s wife of eleven years. After production, O’Connor divorced his wife and she married Dailey. O’Connor eventually found lasting happiness with his second wife, Gloria, and they just celebrated their fortieth anniversary.

For a time in the early 1950s, O’Connor was known for a series of low budget comedies with big box-office returns in which he was partnered with Francis the talking mule. “It was wonderful at first because it was a departure from the song-and-dance man, but after three pictures Francis started getting more fan mail than I did and I said, `This can’t happen.’ But Francis retired from motion pictures and went into politics.”

His favorite film? “I really don’t have one. It was working with the people that made the pictures fun. If I did, it would be Singin’ in the Rain because of all the fun we had in rehearsal.” O’Connor won a 1952 Golden Globe Award for best male performance in a comedy or musical. The stars were a trio of Irish Americans: Kelly, O’Connor and a teenaged, nervous newcomer Debbie Reynolds, who relentlessly chewed gum which at one point she stuck on a ladder and to which Kelly’s hairpiece became stuck.

Kelly, who was not only starting in the film but choreographing and co-directing it as well, felt so overwhelmed by the task that he was short-tempered with O’Connor. He apologized one day when they were out drinking and explained. “Donald, I’m terribly sorry. I’m having a lot of trouble with Debbie. She’s not getting these things fast enough. I couldn’t yell at her because I was afraid that I would lose her for the rest of the picture, and so I yelled at you.”

But the two dancers complemented each other. Whereas Gene Kelly had the roguish, swaggering quality of Irish literary culture, O’Connor was an endearing altar boy who created his niche through self-effacement, charm, resilience and adaptability. While shooting the film, Kelly required O’Connor. who at 5’8″ was slightly taller than Kelly, to move with him simultaneously because they played vaudevilleans who were once in an act together. However, as O’Connor recalls, “I turned to the left and ninety-nine percent of dancers turn to the right. I fretted about that all night and the next day I went in to see Gene and he said, `Which way do you turn?’

When I said, `To the left,’ he said, `Thank God, so do I.’ That’s why we look so well together because our strong side is going toward the left. He [Kelly] couldn’t understand why dancers always turn to the right because when you throw a football, baseball, or anything, if you’re right-handed, your momentum is taking you to the left.”

Throughout the evenings at Lincoln Center, O’Connor deflected any praise or credit from the audience, many of whom were dancers themselves. He lists his influences as: “Every dancer I ever saw. Each one had something that was wonderful.” Fred Astaire was a major influence because of his happy-go-lucky style and also the Nicholas Brothers. “Harold and Fayard are the greatest dancers.” O’Connor paid tribute to all dancers: “We used to steal from each other” he modestly claimed, indicating that he regards his place in dance as part of an extended family.

Amazingly for someone who threw himself through walls, danced on stairs in roller skates, and made acrobatics an art, he never sustained injuries. “Once you’re rehearsed and warmed up, you rarely ever get hurt,” he says. In 1957 O’Connor portrayed acrobat Buster Keaton, whom he had admired, in The Buster Keaton Story. “Buster did the same kind of act in vaudeville as I did. They threw me all over the stage.”

Is an autobiography in the future? “Not yet. I’ve been writing it over the years, and I have to wait for a few more people to die,” O’Connor says, his eyes glinting humorously.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the July/August issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply