His mother was Irish born Emma Jane Whelan. His father’s mother was also Irish. Hitchcock was educated at a Jesuit school and remained a devout Catholic through out his life. Hitchcock also adapted Irish playwright Sean O’Casey’s “Juno and the Paycock” for the screen.

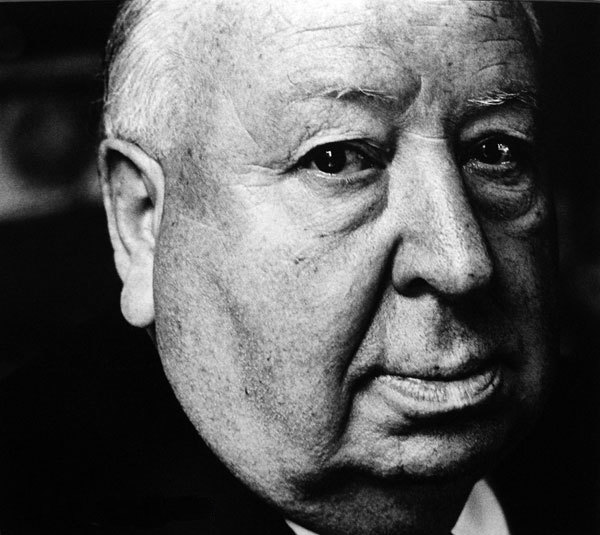

The name Alfred Hitchcock summons up images of the impassive, corpulent, bald-headed man in a black suit who depicted and discussed murder in the most deadpan manner. His movies, most notably Rebecca (1940), Spellbound (1945), Notorious (1946), North by Northwest (1959), Psycho (1960), and The Birds (1963) transformed the suspense movie, and he mocked our fear of murder with his deadpan introductions on his Alfred Hitchcock Presents television series.

Though Hitchcock was not reticent about revealing the motivations behind his artistic decisions or his frustrations with the steamrollering Hollywood studio system, he steered journalists away from his private life. In reality, he had a conventional family life. His wife Alma Reville, who collaborated on his early British movies as a scriptwriter, was an emotional support throughout his life. His only child, Patricia, fondly remembered by moviegoers as the perceptive sister of the heroine in Strangers on a Train (1951), has always maintained that Hitch was a loving, good father, devoid of the sardonic nature attributed to him by casual biographers and the media.

To celebrate The Alfred Hitchcock centennial, the Museum of Modern Art in New York mounted a most comprehensive retrospective, which ran April through June 1999. The exhibition included posters, letters and production material and all of his extant movies.

Patricia Hitchcock, on hand to personally introduce some of her father’s movies, talked to Irish America magazine about her father’s Irish roots, which, she says, he never discussed.

His mother, née Emma Whelan, was born in Ireland as was his father’s mother, Anne Mahoney. Born in the East End of London, home to many Irish immigrants, and educated by the Jesuits, Hitchcock once told Francois Truffaut: “Ours was a Catholic family and in England, you see, this in itself is an eccentricity.”

The Hitchcocks arrived in the United States in 1939 when the director was signed to a contract by David 0. Selznick. The Hollywood lifestyle didn’t change the family’s habits.

“I was raised as a strict Catholic,” Patricia Hitchcock recalls. “My father brought me to church every Sunday.” Indeed, Pat married into one of the most prominent Irish Catholic families in America when, on January 17, 1951, she wed Joseph E. O’Connell, Jr., son of Boston businessman Joseph E. O’Connell, and grandnephew of William Cardinal O’Connell (archbishop of Boston from 1907 to his death in1944). The couple married at Our Lady Chapel in St. Patrick’s Cathedral, New York.

Though Hitchcock made few movies with Irish themes, the three he did make are uniquely Irish Catholic and represent a significant segment of the Irish Catholicism on film. In Hitchcock’s era, few movies identified a specific religious orientation because movies were designed to appeal to a mass audience and divisions were erased. Juno and the Paycock (1929) was filmed with the original Irish Players cast of the Sean O’Casey play. Though crudely made in that early sound film era, it is far superior and truer to the John Ford version of another O’Casey play The Plough and the Stars (1936).

Hitchcock loved the play with its morally marginal message which pussyfoots around the Irish Uprising and oppressed Catholic theme. Under Capricorn (1949) explores the life of the transported Irish in 19th century Australia; the storyline is flawed and the film is further marred by the inauthentic casting of Ingrid Bergman as a dipsomaniac emigrant Anglo-Irish aristocrat married to her transported Irish stable hand (Joseph Cotten) but it is one of the few films on the theme of the Irish Diaspora.

I Confess (1953) is one of the few movies ever made on the sanctity of the confessional. Father Michael Logan (Montgomery Clift) is the prime suspect in a murder and he cannot tell the police who the real murderer is because the murderer confessed the crime to Father Logan in confession.

A fourth film, The Trouble With Harry (1955) is not identified as Irish but is as close to an Irish shaggy dog story as it could possibly be. It is a moveable Irish wake story; a hunter has found a corpse in the woods and cannot be sure he didn’t kill him so, with the help of newly found compatriots, the body is moved from place to place to avoid discovery. This story has resonances to the tale of the Irish poacher in old Ireland who in self-defense killed the aristocrat’s gamekeeper and had to hide the body.

Hitchcock embraced such indigenous Irish themes as distrust of authority, and guilt.

He traces his fear of the police from his father William Hitchcock and from the Jesuits.

The Jesuits at St. Ignatius College in London instilled in him, as he told Truffaut, “A strong sense of fear…. moral fear the fear of being involved in anything evil.” The typical Hitchcock hero is involved in a Catch 22 situation in which he is framed for a murder and is running from the police as much as from the real villains.

Another reason to claim Hitchcock as Irish is the fact that he made a star out of Maureen O’Hara in Jamaica Inn (1939), her first significant film, which enabled her to come to America and become a prominent Irish-American. The three films in which he starred Irish American Grace Kelly, Dial M for Murder (1954), Rear Window (1954) and To Catch a Thief (1955) made her legendary.

Note: This article was originally published in the August/September 1999 issue.

Leave a Reply