It’s been 15 years since the Hunger Strikes in Ireland left ten men dead and changed the course of Northern Irish politics. Now a new movie gives voice to the suffering of the mothers whose sons died on hunger strike. Jim Dwyer talks to filmmaker Terry George about his latest work, Some Mother’s Son.

It’s been 15 years since the Hunger Strikes in Ireland left ten men dead and changed the course of Northern Irish politics. Now a new movie gives voice to the suffering of the mothers whose sons died on hunger strike. Jim Dwyer talks to filmmaker Terry George about his latest work, Some Mother’s Son.

Terry George settled into the big Aer Lingus seat next to mine, slipped off his shoes, and munched on a cracker spread with a fancy pate.

It was early December and I had just finished covering Bill Clinton’s visit to Ireland. And Terry, after months in Ireland directing a film, was headed back to the United States, to his wife and kids. He was a friendly acquaintance from New York, a wiry red-headed man who, for years, moved at a half-sprint among the odd writing jobs that kept him afloat.

Until suddenly, he soared,

A few years ago, he wrote the script for In the Name of the Father, and transformed the history of the Guildford Four from a newsreel about injustice and politics into the story of a father and son discovering each other in the malignant belly of a prison.

His script made it to the finals of the Academy Awards. And now, at age 43, Terry has directed his own film, a great triumph for a man who served three years in Northern Ireland’s Long Kesh prison and a decade of hard struggle in New York. The day before our flight, he had wrapped up the filming and shut down the production.

So I was delighted to have him as a traveling companion but there was just a slight problem as we sat on the plane, I could not remember the subject of the movie, and desperately tried to rally the conversation until the topic came up.

“You must be relieved to have it all over with,” I said.

“Now I’m worrying that I forgot to shoot something,'” he said.

“Was it a decent budget?”

“We spent $7.2 million,” he said, which is decently small by Hollywood standards.

But was it too small for George’s movie, whatever it had been about?

It seems like all the best movies are made on small budgets,” I blustered. `The directors keep an eye on the story and can’t get distracted by the expensive gimmicks.”

“You can tell any contemporary story for $500,000 or for $50 million,” said Terry. “If you’re anxious to tell a story, you will tell it, within any budget. Hollywood looks at a story and figures out how they can market it. It’s like a cow being led around an auction ring, and the buyers figure they can get x-amount of beef from it.”

With that, he reached for another fancy hors d’oeuvre from the air hostess. Suddenly, the topic clicked.

“The Hunger Strike!” I said. Got it. Ten people starve themselves to death. “A very, ah, interesting, um, topic.”

The words sounded like a mannerly insult, from which I immediately tried to retreat. “How did you manage that story?”

“It’s actually the story of two women,” said Terry. “Two mothers.”

Four months later, Some Mother’s Son was given its first public screening in New York.

From the opening moments, with a terrifying foot-stomping security forces raid on a Christmas dinner, to a final, silent glance between the two mothers, it is a movie of vast power and integrity, rich in suspense and black, gallows humor.

As a prisoner’s mother lights up a cigarette, she remarks: “I’d give them up myself, only for this bloody country. Sure you could be dead on the minute.”

When it opens this fall, Some Mother’s Son — the tentative title as this goes to press — will grip its audiences as tightly as The Killing Fields did a decade ago. In that movie, based on the work of Sydney Schanberg, the story of the Cambodian holocaust is told through the suffering and struggles of Dith Pran. In Northern Ireland, we are guided through a more complicated moral universe by two women, Kathleen Quigley and Annie Higgins.

“We wanted to give the story a universal context,” said George, “and the way to do that was by telling it through the experience of the two mothers.”

The circumstances of the Hunger Strike hardly need to be repeated for the readers of this magazine, but for the mass audience, George deftly sketches the conflict: in 1981, at the dawn of the Margaret Thatcher era, the British government made a new effort at containing the armed republican campaign in the six counties of Northern Ireland.

The IRA men were not soldiers, said the government. They were brutal criminals, not prisoners of war. They would not be allowed to resist prison regulations. They would wear prison uniforms, and live by prison rules. They would have no political status.

To fight back, the republican prisoners went on hunger strike.

If only for the argument over status, a feature film about the hunger strikers would resonate today in the debate over “decommissioning” of the IRA before talks begin. Armies do not disarm. Criminals do. But the story Terry George tells is much bigger than mere temporal politics.

The events of 15 years ago were the Irish jihad: instead of suicide bombers blowing up shopping malls and buses, the hunger strikers imploded, like collapsed stars, with a gravity that was powerful and terrible. Those closest to the strikers could not escape their gravity, even if they wanted to. The last stages of starvation involve coma. The prisoners no longer could knowingly refuse food or water. Their next-of-kin would be empowered to make that decision.

The burden shifted to the mothers.

“The mothers had to participate in the life or death decisions of their sons,” said George. “They were being challenged to refute their sons’ causes to save their lives. That was what the story was about.”

Around their dying sons swirled the currents of republican and British politics. Fierce debates over policy raged between the authorities in Northern Ireland and the Thatcher government.

In the film, these disputes unfold in quick, vivid strokes through minor characters. As the horrors of starvation advance — the seizures and pneumonia and blindness — so, too, do the most repellent features of statecraft: tactical indifference to the starving men. “A criminal is a criminal is a criminal,” Margaret Thatcher intones.

A priest who serves the nationalist community and wants the strike to end accuses the main Sinn Féin character, a hybrid of Gerry Adams, of needing more hunger strike deaths for the pageantry of IRA funerals.

“The funerals were pageants,” said George. He convinced the principal financial backers of the project, Castle Rock, to spend an additional $250,000 so he could stage the mass crowds of the Bobby Sands funeral, which was attended by some 100,000 people. George managed to do with a few thousand.

“You’re working with an inch by inch and a half frame of film — the trick is to make people feel that beyond the rectangle is the mass of humanity,” he explained.

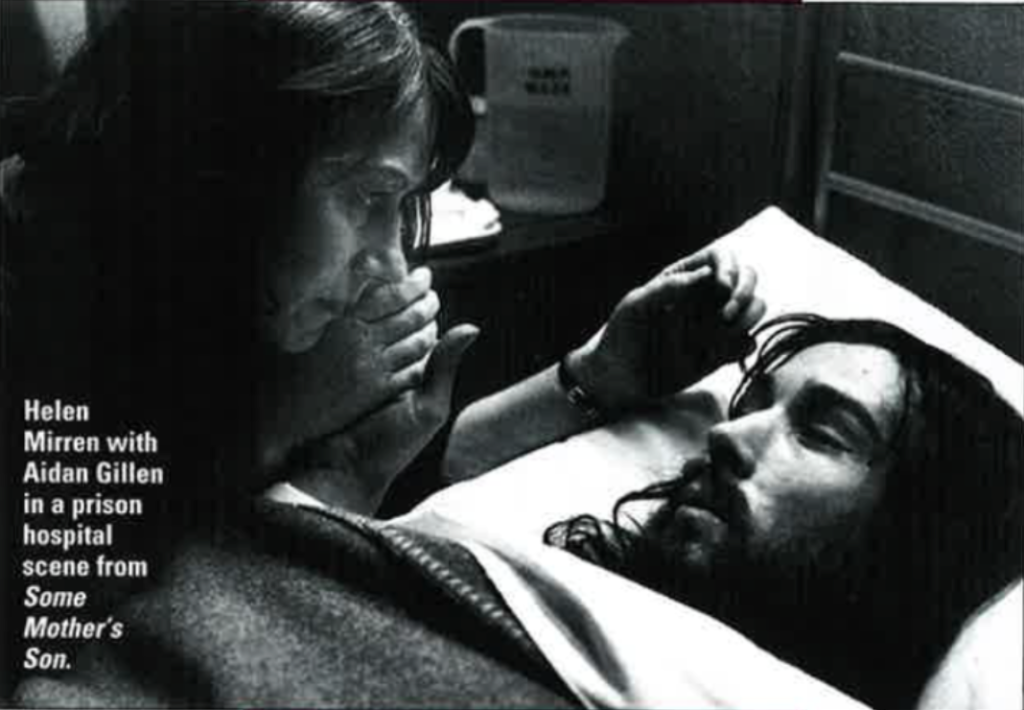

Yes. But the great gift of this movie is not the magic worked by George in making his 2,000 look like 100,000; it is the centering of all our passion on the two women we cannot stop watching. One mother, played by Helen Mirren, is a middle-class suburbanite, who is unaware that her son is involved in the IRA until his arrest. The other, performed by Fionnula Flanagan, is a committed republican farm wife.

It is hard to think of two more interesting and compelling female characters in modern film. Mirren and Flanagan are so equal to their characters that we do not think for a moment that they are acting. “Helen Mirren may be the best female actor in the world,” remarks George. “And Fionnula Flanagan — to say that she lobbied vigorously to get the part — well, that’s understating it. She said she was right for the part and she proved it.”

The mothers are forced together. They spar. Mirren’s character, Kathleen, despises the IRA’s violence. Flanagan’s Annie would walk out of her way to annoy a British army patrol. But both their sons are starving. And both women need each other. Annie brings fresh eggs from the farm to her suburban friend. Kathleen surprises Annie by giving her driving lessons on a strand.

As Kathleen moves from her comfortable life into the small, mad circus of West Belfast, she is entranced by the images around her: the gray ghosts of security Land Rovers, the police with visors across their face, the huge wall murals of the Falls Road. Each woman faces the emotional and moral turmoil on her own terms.

The two mothers and their sons are “composite characters,” says George. “But every political event in the film, I can match up with an actual event.”

If George has a gift for taking the large political story and making it personal, perhaps it is because he has been cursed with interesting times. He grew up in the Twinbrook section of Belfast, not far from Bobby Sands. He was interned for six weeks in 1972 on charges of associating with the IRA.

“I wasn’t, I was just associating with other Catholic kids,” he said. “But it was round-up time.”

He joined the Irish Republican Socialist Party, a left-wing alternative to the IRA organized by Bernadette Devlin McAliskey. He was arrested in 1975 driving a car with a passenger who had a gun, and was sentenced to six years in Long Kesh. He was released in 1978 and studied at Queens College. By 1981, the year of the Hunger Strikes, he was working in Galway and commuting back to Belfast.

“It was the defining moment of The Troubles on a huge scale,” he said. “Even in the face of revulsion against the violence of the IRA campaign, the Hunger Strikes hit a nationalist vein in Ireland, north and south. It was like the reaction after Bloody Sunday.”

That summer, he met American journalists Pete Hamill, Denis Hamill, and Michael Daly. “They were sort of my runway to the United States. It always seemed to me in America you could make a living in the arts. At home, until the last few years, it was only eccentric people that made their living in the arts.”

The path back home, to Some Mother’s Son, began in New York. George wrote a play, The Tunnel, about an escape attempt from Long Kesh. It was directed at the Irish Arts Center by Jim Sheridan. From this struggling band of writers and actors on West 51st Street came a small industry of filmmakers. Sheridan went on to write and direct My Left Foot. George worked at the Arts Center, then wrote a script based on a book written by one of the Guildford Four, Gerry Conlon. That became In the Name of the Father, which Sheridan directed.

George, who now lives in suburban New York, has been married for 17 years to Rita Higgins, a social worker, writer, and advocate for women and families. They have two children, Orla, 15, and Seamus, eight. Both kids appear in bit parts in the new movie.

The entire family, including Terry’s mother, arrived for the first public screening in March. A lovely reception was catered personally by the George family and friends, a homely reminder that $7.2 million only goes so far in the film business. But then the audience filed silently and slowly out of the screening room, mesmerized by the powerful story. The money had gone every mile of where it was needed. I saw Terry grab an appetizer. And the thought rose that no one who sees Some Mother’s Son will ever have any trouble remembering what it was about.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the May/June 1996 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply