Maeve Brennan (1917-1993), the Dublin-born writer has been described as “Irish literature’s best kept secret,” was as striking in appearance as she was in talent – beautiful, chic and effortlessly witty. From 1949 to 1981, Maeve was a staff writer for arguably the greatest literary magazine in the world, The New Yorker. Yet like so many brilliant writers and artists, Maeve was “touched with fire,” plagued with a mental illness that brought her first notoriety, then later, tragedy as her beautiful prose sank into obscurity.

Maeve was born in 1917 to Robert and Una Brennan both militant revolutionaries in Ireland’s War of Independence who named Maeve after the fearsome Queen Medb of Irish folklore. Her father was frequently in prison or on the run, while the family home was invaded by the British forces. With freedom won, Ireland’s leader Eamon de Valera rewarded Bob Brennan’s loyalty by appointing him as the first Secretary of the Irish Legation in Washington, DC. The Brennan family, including 17-year-old Maeve, emigrated.

The New World, particularly New York City, became her home until her death but the Old World of Ireland was always the setting of her novels and short stories. Like James Joyce, another exile who wrote only of a place left in youth, Ireland stayed forever in her consciousness. Maeve and Joyce had a similar fixation, Dublin and especially Dubliners, what they thought and how they lived.

When Bob Brennan’s Washington tenure was over, as the family was preparing to return home, Maeve, emboldened by her time in America, announced she was staying to live in New York and become a writer. She knew that dream couldn’t be realized in 1940s Ireland, remembering the time when, much younger, she confided to her sister that she wanted to be an actress. The sister chided her, “Who do you think you are? Don’t go getting any notions into your head!” (Irish journalist Fintan O’Toole once said that phrase, “could have been emblazoned on the Tricolour.”)

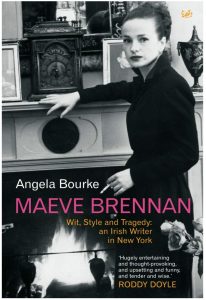

Maeve first worked at the New York Public Library until 1943 when Irish-born Carmel Snow hired her to write about fashion for Harper’s Bazaar. It was there that Maeve developed her signature style – dark lipstick, dressing only in black, and pinning a white rose on her lapel. Because of her diminutive size, she wore very high heels and piled her thick chestnut hair atop her head.

Her writing in Harper’s impressed New Yorker head, William Shawn, who recruited her to write fashion pieces and book reviews for his magazine in 1949. William Maxwell, the magazine’s fiction editor who became Maeve’s closest friend, saw her brilliance and began shepherding her work. Her short stories began to be published in the magazine in 1950, the first entitled “The Holy Terror.”

It was Maeve’s mordant wit that prompted Shawn to give her a weekly column called “The Long-Winded Lady,” which ran from 1953 to 1968. Maeve observed the quotidian life of New Yorkers, offering her idiosyncratic take on their behavior. She followed, eavesdropped, and speculated on strangers from straphangers to the trombonist on her roof to a man who never stopped combing his hair. “The Long-Winded Lady” became a must-read in The New Yorker; John Updike claimed Maeve’s column helped “put New York back into The New Yorker.” Her observations and intimate, somewhat vulnerable voice forever changed the magazine’s dispassionate and masculine tone. It wasn’t until 1969 that The New Yorker revealed the identity of the anonymous Long-Winded Lady: Maeve Brennan.

When she joined the magazine, it was a world of American men, but Maeve held her own, as her male colleagues gravitated towards her beauty, elegant prose and brash repartee delivered in a soft Dublin accent. Roger Angell noted, She wasn’t one of us – she was one of her.” Maeve soon became the star of Costello’s, the local bar where the writers from The New Yorker congregated for after-work drinks and boozy lunches. Her extravagant generosity and raucous conversation were legendary, as was her ability to keep up with the men drink for drink.

Maeve lived first in Greenwich Village but being compulsively peripatetic, she moved from apartments to hotels to apartments again. She called herself a “traveler in residence” as if she were just passing through, never settling down, still the exile. She had a large dog, Bluebell, and several cats that always traveled with her. Maeve was able to pack her animals and possessions into a single taxi because she usually left most of her clothes and furniture behind. Such insouciance led many to believe the character of Holly Golightly, another chic bohemian, was based on Maeve Brennan. Both were madcap but only Maeve slipped into madness.

When Maeve was 36 she embarked on a dangerous marriage, one that may have precipitated her decline. She became the fourth wife of a writer from the magazine, a man whose affect was as theatrical as his name – St. Clair McKelway.

Both Maeve and McKelway were hard-drinking, volatile and incapable of handling money. At their wedding, one guest said they were “like two children out on a dangerous walk, both so dangerous and so charming.” They moved out of the city to Snedens Landing, drank a lot and became friends with F. Scott Fitzgerald’s friends, Sara and Gerald Murphy. During this time Maeve wrote a series of stories, Herbert’s Retreat. After five years, the marriage ended and Maeve returned to New York, now burdened with the debt that resulted from the couple’s reckless spending. St. Clair McKelway went on to have another nervous breakdown and take a fifth wife.

Maxwell believed that Maeve produced her finest work after the split with McKelway. Her short stories, particularly those about the Derdons, a couple living in a loveless marriage, “doing as they had been told they ought to do” were evocative in their tragic way. Her reputation was rising as her life began unraveling. By 1969, Maeve, though she was writing feverishly and her stories still appeared in The New Yorker, was forgoing her impeccable grooming. Her lipstick now a shapeless slash, her hair went uncolored, and she had bouts of paranoia, convinced someone was putting cyanide in her toothpaste.

Over the next decade, the woman who had every imaginable gift flamed out most spectacularly. She became a drifter about New York, living a flophouses, shelters, and occasionally homeless, sleeping in the Ladies Room at The New Yorker.

She hallucinated, tended to sick pigeons and had occasional bursts of violence. She had joined the company of artists and writers who had descended into “a fine madness” – the space where the artistic temperament collides with psychosis and, frequently addiction.

In 1981, she wrote her last essay in The New Yorker, which had a poignant passage, almost as if her subconscious was addressing her exile: “Yesterday afternoon, as I walked along Forty-second Street directly across from Bryant Park, I saw a three-cornered shadow on the pavement in the angle where two walls meet. I didn’t step on the shadow, but I stood a minute in the thin winter sunlight and looked at it. I recognized it at once. It was exactly the same shadow that used to fall on the cement part of our garden in Dublin, more than fifty-five years ago.”

Soon after she wrote that, Maeve disappeared from view and was largely forgotten.

Years later, Mary Hawthorne, the magazine’s new editor saw a tiny, unkempt, unclean woman staring at the floor in the lobby of The New Yorker. She learned it was Maeve Brennan. The editor contacted Maeve’s former colleagues and together they got her into a hospital and on medication. She died in Lawrence Nursing Home in Rockaway, New York, of a heart attack on November 1, 1993. Only two of her books were published in her lifetime: Out of Never-Never Land (1969) and Christmas Eve (1974). Neither book was released in Ireland.

Happily, Maeve is being rediscovered in America and discovered in Ireland. In 1997, William Maxwell published a collection of her stories, The Springs of Affection: Dublin Stories, which received rapturous reviews. Irish writer Anne Enright compared Springs of Affection to Dubliners: “These stories feel transparently modern, the way that Dubliners by Joyce feels modern. It is partly a question of restraint… Brennan remains precise, unyielding: something lovely and unbearable is happening on the page.” Three posthumous releases of her work included a collection of her “Long-Winded Lady” columns (1997), The Rose Garden (2000), and The Visitor (2000). She had written The Visitor as a young woman working at Harper’s Bazaar in 1945.

After her death, William Maxwell came across a letter she had written wherein she pretended to be him. The letter was from one of her fans asking for more stories by Maeve. In her most sardonic voice, she wrote her own obituary:

Dear Mr. Boyce,

I am terribly sorry to have to be the first to tell you that our poor Miss Brennan died. We have her head here in the office, at the top of the stairs, where she was always to be found, smiling right and left and drinking water out of her own little paper cup. She shot herself in the back with the aid of a small hand mirror at the foot of the main altar in St. Patrick’s Cathedral one Shrove Tuesday.

The faux letter went on, ending with “One might say of her that nothing in her life became her.” Only Maeve could have – and would have – written that.

Wow! What a tragic life. I am going to read her stories when I can find them!