Irish Architect James Gallier Sr. left an indelible mark on New Orleans with his masterful Greek Revival designs in the 19th century. His story began in Ireland where he was born James Gallagher.

By Ray Cavanaugh

There are a number of reasons why someone might change their surname. The reason might be as mundane as marriage. Or it might be as urgent as trying to escape a genocide. In other cases, a change of name might bring better job prospects. It seems this was the reason why James Gallier, a 19th-century New Orleans architect, operated under the Francophone surname of “Gallier” when he was actually a Gallagher.

James Gallagher was born in Ravensdale, County Louth, on July 24, 1798. His father, Thaddeus Gallagher, was a builder and architect, according to the Dictionary of Irish Architects (dia.ie). He also had a younger brother, John Gallagher, who worked in the building trade.

Some sources say James Gallagher studied architectural drawing in Ireland. Either way, as a young man, he worked with his brother on building projects in Dundalk, County Louth, before heading to England. There he would marry Elizabeth Tyler (their son, James Jr., would eventually become an architect).

Over a ten-year period in England, Gallagher would help build structures ranging from factories to schools to prisons. Perhaps his most intriguing assignment was his design of the Chinese Bridge at Godmanchester.

Despite the various commissions he received, he fell into financial trouble. In 1832, then age 34, he immigrated to the United States.

In New York, he met a pair of architects – brothers Charles and James Dakin – and worked for them. A problem soon surfaced, though, as it became clear that the architectural profession was becoming oversaturated in northern U.S. cities.

So, after just two years in New York, Gallagher decided to launch an architecture firm with Charles Dakin down in New Orleans. Although technically part of the upstart American nation, New Orleans was culturally still very much in the French colonial period.

Somewhere during his migration down South, Gallagher became Gallier.

The partnership with Dakin disbanded within a few years, but Gallier had no trouble finding projects on his own. Putting his hidden Irish thumbprint all over the city, he would emerge as NOLA’s leading practitioner of the Greek revival style much in vogue at the time.

In 1845, shortly after his wife’s death, he completed New Orleans city hall, now known as Gallier Hall. He then designed the four-story, redbrick Pontalba Buildings (later completed by architect and Cork native Henry Howard) that spanned a whole block of the city’s ever-vibrant downtown.

Gallier, who also built private residences for wealthy Southerners, then designed the St. Charles Hotel, which boasted 350 rooms and exceeded 200 feet in height, making it the tallest building in New Orleans at that time, according to the website nolatours.com.

Additionally, he helped stabilize the foundation of St. Patrick’s Church on Camp Street, which was the first English-speaking Catholic Church in the heavily French city.

Although he enjoyed a lofty professional reputation, various fires would claim much of Gallier’s handiwork. In this regard, his bad luck was almost uncanny, as if the stars had aligned against him for forsaking his Gallagherhood.

Around the year 1850, Gallier retired due to health troubles, the most severe of which was his declining vision. He let son James Gallier Jr. take over the business and then spent much of his retirement traveling with his new wife, Catherine Maria Robinson.

Gallier eventually wrote and published an autobiography, though it is not especially reliable. For one thing, it “laid claim to a number of buildings, which were in fact designed by others,” as reported by the Dictionary of Irish Architects.

The autobiography also says that its author was born a Gallier and that his father was also a Gallier. The only time “Gallagher” receives mention is for the author to point out that it has “a more guttural sound” than “Gallier.”

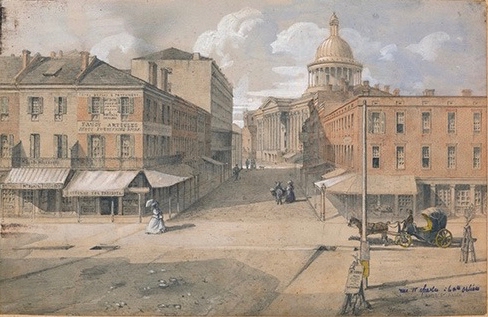

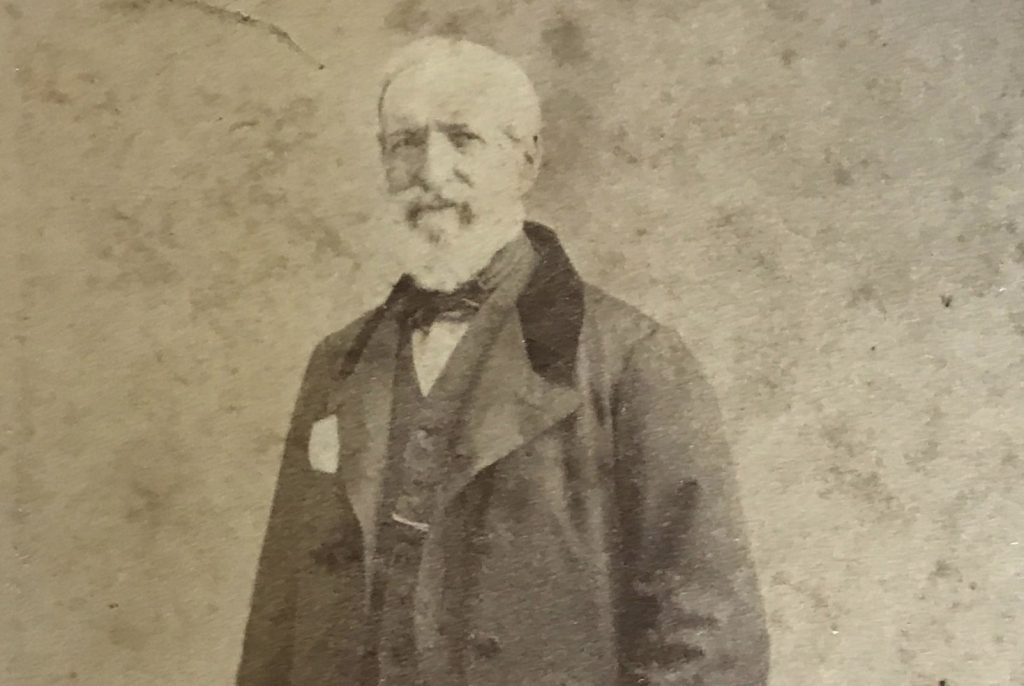

Left: Barton Academy in Mobile, Alabama, designed by James and Charles Dakin and James Gallier in 1836. Center: Gaston de Pontalba (d. 1875) – 1848 drawing by Gason de Pontalba. Pencil, watercolor, and goache on paper. Right: The St. Charles Hotel burning, January 1851.Artist unknown.

On Oct. 3, 1866, Gallier, then age 68, was with his wife on a passenger steamboat off the coast of Georgia, when an oncoming hurricane caused the ship to capsize. The vast majority of the 250 passengers – including Gallier and his wife – did not survive.

There ensued complicated court proceedings to determine whether Gallier’s side of the family or the wife’s side should receive the inheritance. If the wife survived her husband, then her children from a previous marriage would receive the estate. But, as both Gallier and his wife died in the same disaster, it was basically impossible to determine with certainty who died first amid such a chaotic event with massive fatality.

Gallier’s side won the verdict, but ill fortune would eventually strike the next Hidden Gallagher generation: James Gallier Jr.’s most celebrated architectural work, the French Opera House, burned down, thereby meeting the same fate as so many of his father’s contributions.

On a more favorable note, the Gallagher surname remains as strong as ever. And in more recent decades, America has seen a phenomenon in which people – especially political and judicial candidates – are adopting Irish surnames instead of ditching them. These days, you’re more likely to encounter a fake Gallagher than a hidden one.

Left: St. Patrick’s Church, New Orleans. The work was completed under the direction of architect James Gallier who designed most of the interior, including the high altar. St. Patrick’s parish was the second established in New Orleans. The first service in the completed church was held on February 23, 1840 under the pastorate of Father James L. Mullen. Center: Window on the right side of St. Patrick’s Church, near the front. Right: Gallier Hall on Lafayette Square (1853).

Leave a Reply