A Story of Ireland

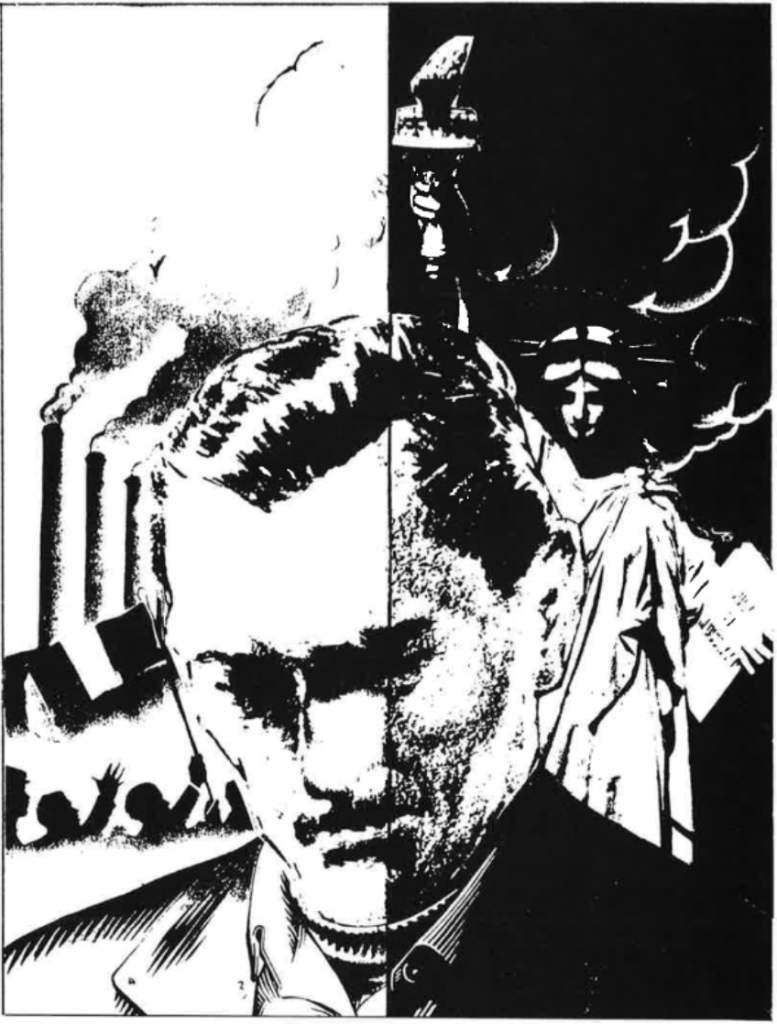

Whenever Michael Walsh thought he was finished at last with Ireland, all of it would come flooding back, like a sudden wave on a glassy sea. He had tried to rid himself of that sad green country with cheap whiskey in too many bad bars in a city that was not his own. And now, on this perfect spring day in his eleventh year of New York exile, he could feel Ireland once again making its terrible move.

He pulled the Chevy around the long wide curve of the Belt Parkway, passed under the Verrazano Bridge, and reached for his ninth cigarette of the morning. He used the car lighter, afraid of losing focus while fumbling with a match, nervous about accident or blunder. The nerves were understandable. Michael Walsh was going to Kennedy Airport to meet his daughter, Shivaun. He had not seen her since she was 12 years old. She was then a plump quiet child with the wary eyes of a permanent stranger. They had exchanged letters over the years, and he knew the outlines of her life, but he didn’t know her. Now she was a woman. And Michael Walsh, almost 60, overweight, balding, smoking too much, had spent the days since her telegram arrived with the warm dirty rain of Belfast falling through him in a steady drizzle.

“I didn’t know you had a daughter,” his friend Miguel had said the night before in Donnolly’s.

“I do.”

“So you had a wife, too,” Miguel said. “I had.”

Yes, I had a wife, he thought, and a son and a daughter, and Ireland. And lost them all. But he didn’t say that to Miguel. When Michael Walsh was young, he wanted Ireland to be like stone in the hands of a great sculptor, a wedge of marble lifted from the quarry of the world, hard, permanent, to be shaped by human hands into a thing of beauty. He thought a marriage could be like that, too. But now there was no stone, only a collage. And when Miguel, who was from an island too, asked him about Ireland, he could never explain. Ireland was wet wool and Woodbine cigarettes, it was dirt-stained brick, it was candles guttering in too many drafty churches. It was the smell of rolls on Sunday morning, bacon frying, mugs of scalding tea, the earth of the cemetery on the Whiterock Road, rich and loamy after a rain. Always the rain, and the smoky haze, and the whistles blowing from Harland and Wolff’s shipyards at noon, Cadbury’s chocolates, rotting teeth, the shiny surface of wet granite on the looming public buildings, and Queen Victoria’s smug Germanic face, squatting in front of the city hall, sneering at them all. If he could tell it all to Miguel, he would speak of Ireland. But then there would always be the rest of it, too, and that he could never tell to anyone.

“I have a wife in Cuba,” Miguel said, “I used to hear from her. She used to write. But after ’66, I never heard from her again.”

“I understand,” Michael Walsh said, drinking thin pale beer in this Brooklyn bar on the wrong side of the Atlantic.

Miguel sipped his rum, then said: “How come you left Ireland?”

Walsh laughed. “I was leaving all my life,” he said, and turned to the television set.

Just past the Knapp Street exit, the traffic slowed, then clogged. Walsh rolled down the window, dropped his cigarette butt onto the highway. He hated traffic jams. A traffic jam had caused all the trouble that time in London in ’59. He was staying then in a bed and breakfast house on the Bayswater Road, a stale-smelling place where the gold leaf peeled off the plaster of the picture frames and the sausage tasted like cornmeal. When the hard men came to visit him, he had opposed the bomb; he’d said that bombs were bad politics, they killed the innocent, they lost the sympathy of the press, they made the IRA look like cold-blooded killers, and what did stupid murder have to do with Ireland? But they’d overruled him. They’d said that the target was military, a barracks and a car park, that they’d destroy trucks and cars and if anyone died, the casualties would be soldiers, and the death of soldiers was always fair in war. So they’d made the bomb in his room on the Bayswater Road, and then Jimmy and Frankie took it away in a stolen car, heading across London to the barracks. It was all very simple; they’d park the car and leave the bomb to the timer, and by the time it went off, they’d be in Camden Town, ready to leave again for Ireland. But there’d been a traffic jam. The seconds, then the minutes ticked away, while Michael Walsh waited in the room on the Bayswater Road, and when the bomb went off it took Jimmy and Frankie with it, and an accountant and a publican and three schoolchildren. When the knock fell on his door that afternoon, he knew it wasn’t Jimmy and Frankie; the State knocks at the door in a very special way. And it was the Special Branch, all right, he knew then that he was gone.

Bloody traffic.

What is it, anyway? A flat tire. Someone up there with a flat tire, and no shoulder on the road. Hurry. Please hurry. If I miss the plane, I’ll lose her.

She was born while I was in prison. I’ll never be forgiven for that, he thought. Not by Rosaleen. My wife. My dark Rosaleen. Not by God. Not even, perhaps, by the girl herself. Born in February 1960, with me dying a day at a time in Dartmoor, in the strange chilly country or the ancient enemy. That day, when his wife Rosaleen gave birth to his daughter, she had cursed him, and cursed the IRA, and cursed Ireland. She told him all of that later, his dark Rosaleen. But all he knew in Dartmoor was that the child was born, and named Shivaun. Rosaleen told him all this in her monthly letters, in the crisp curt language that told him everything he ever needed to know about the distance that had grown between them.

After a while, the letters came less frequently and then not at all, and Michael Walsh did his time engulfed in gigantic loneliness. When he was young, and full of Ireland and history, he had been jailed too. But that had been fun. He spent most of the Second World War in the Crumlin Road jail with all the others and Joe Cahill who worked with the butcher shop and kept them laughing with good crack. They learned Irish together, and studied history, and the wives of the married men brought them packages of food, and they could have visitors and read the news. He always thought of the Crumlin Road as his University. But Dartmoor was a pit of gigantic loneliness.

His son Brendan was born the following year, red-haired like the Walshes, with dark eyes like the Devlins. He was working with Dinny Collins then, cutting stone. In the studio that Dinny called The Scullery, a place he’d first visited as a boy, and where he’d discovered Ireland and art and Rodin. Bloody traffic.

Move. Please move.

Dinny Collins was an old man mad for stone. If grass was the skin of the world, he always said, and earth its flesh, then stone was its bone. Michael Walsh was 15 in the glorious summer of “39, when he wandered into The Scullery. The studio was out beyond the edge of the city, and in it he found this man, his face seamed. and folded, his hair as white as the stone dust on the floor, wifeless and childless, bursting with energy and life.

“Don’t stand there like an eejit,” he said. “Make yourself useful. Mind the tea.”

And so he’d begun. Dinny Collins carved headstones for cemeteries, and an occasional portrait bust of a businessman he liked. But he did his own work, too. There was a locked closet off the back of The Scullery, and after Michael Walsh had come every day for a month to make tea, to work on the finish of headstones with pumice, to sweep up, and finally to begin cutting stone with maul and chisel, Dinny Collins had unlocked the closet. Inside were the carved heads of Pearse and Connolly, of Michael Collins and Countess Markievicz, of Wolfe Tone and Parnell, too, the men and women who had dreamed the Irish revolt. And to explain them, Dinny Collins told their stories, and explained that they were locked away until that day when the Six Counties would be joined to the south and Ireland once again completely free. “That’s marble, lad,” he said, running his calloused fingers over the features of Connolly, who had been executed while tied to a chair. “It’ll last forever.”

Michael Walsh was thrilled. The marble figures in the closet became part of his dream, too. The dream of Ireland. He spent all of his free time with Dinny Collins, watching the old man slice into stone, the chisel always finding the grain. Cutting without goggles because Michelangelo and Rodin had not worn goggles. The boy had never heard of these men and said so, and Dinny Collins found pictures he had torn from The Illustrated London News and showed them to the boy. Michelangelo was too immense, too large, too finished and perfect and final. But Michael went mad for Rodin. These were human beings emerging from stone, sensual men and women, touching each other, embracing, even kissing, celebrating life and struggle.

“Look, will you, at the way he doesn’t over-finish,” Dinny Collins said. “He knows nothing’s ever finished in life. But there’s something else. He’s telling the stone he loves it, he’ll let the stone exist, too. What love …”

Slowly, Michael Walsh learned deeper lessons. Cutting a headstone could give you a sense of reticence and dignity in the face of death; working with stone, from which you could make a tulip or a cathedral, gave him a sense of order and symmetry that did not exist in life.

“Look at Rome, lad,” Dinny said once. “What’s left of all that glory? Stone, lad. Stone.”

At last. Moving again.

Dinny Collins, he thought. I’ll miss you every day of my life.

At the airport, he followed the signs for the International Arrivals Building, took a ticket, pulled into the parking lot. He was an hour early and, relaxed now, he walked to the steel and glass building and looked for his daughter’s flight on the blinking electronic board. On time. He drifted into a coffee shop.

Over coffee, he remembered coming home that time, on the night boat from Liverpool, in the brutal winter of 1969. His clothes were coarse and baggy and ill-fitting, he had 14 quid to his name, his hair was thinning, but he was free.

He walked all the way home, in the frail persistent Belfast rain, a decade of his life gone forever, not yet old but no longer young. He turned down the narrower streets off the Falls, and then heard his name called.

“Michael Walsh?” the voice said. “Is that you, Michael?”

He turned and saw a man he didn’t know. A young man with a long nose under a cloth cap. “By God, it is you, isn’t it?” the man said. “I’m Michael Walsh.”

“A hero,” the man said, shaking Walsh’s hand. “A true hero.”

Walsh protested. “I am no hero, and besides that was in another time, and the time is past.”

“The time is never past,” the younger man said, and Michael Walsh nodded goodbye and walked on until he reached the small house with the scrubbed flagstone walk and the rain falling on its slanted roof. Across the street, a postman was making his rounds, and for one terrible moment Walsh wanted to turn and leave and keep on going. Then the door opened.

Rosaleen stood in the doorway, out of the rain, pushed a hand through gray hair, wiped the other hand on an apron.

“Well?” she said. “Are you goin’ to stand there? Come in.”

He took off his soaking jacket and hung it on a peg, beside other clothes, and Rosaleen went to the kitchen and began to rattle pots and pans. He looked up the stairs and saw his son staring at him.

“Hello, Brendan,” he said, and the boy, who was wiry and red-haired and tall for 17, took a tentative step and then came clattering down the stairs, rushed to his father, and began to cry.

“Oh, Da, oh, Da, oh, Da,” the boy said. “Oh, Da.”

And as he hugged the boy, who was no longer a boy, and heard bacon sizzle on a pan, and felt that perhaps everything would be all right, he saw the girl. She came from some other room upstairs, dressed in a gray school uniform, pudgy and shy.

“You must be Shivaun,” he said, separating gently from his son, smiling at her. She said nothing, came down one step and then another. “I’m your father.” She stood facing him now, her face trembling. Michael Walsh put his hands on her shoulders. “Let me look at you.” At last, she smiled.

“Hello,” she said.

He put an arm around her, and the three of them went to the kitchen table. They watched him cat, Brendan firing questions, about prison, and the journey home, and then telling Michael Walsh what was happening here, the civil rights movement and the way the B-Specials looked on in silence when the marchers were stoned and beaten at Burntollet Bridge, and how a man named Ian Paisley was filling Belfast with hatred and fear, and how some of them felt in the Falls that it would come to violence and there had better be an IRA.

“That’s over, lad,” said Michael Walsh. But the boy talked on and on, about injustice, gerrymandering, bigotry; about the unemployment among Catholics; and about the Republic. Walsh ate greedily; no meal had ever tasted so good. But he said nothing to encourage the boy. The girl said nothing. She watched. And Rosaleen listened. Michael turned the talk to school, to languages, geography, writing. Anything but history. The girl wanted to learn French. She wanted to live in Paris, France.

“You can visit the Rodin Museum there,” Michael said. “He was a great sculptor.”

Her eyes brightened at this, and he promised to take her around to see some sculpture in the morning. The boy rose nervously, as if this talk of art and sculpture offended him; he said he would go down to get his father some Woodbines, and was off. The girl retreated after a while to her room, and then Michael and Rosaleen were alone.

“Why did you stop writing to me?” he asked softly. She looked at him, clear-eyed and quiet for a beat. And answered:

“There was nothing left to say.”

That night, and in the weeks that followed, he came to know the depth of her fury and her bitterness. He had lost his youth in prison, and she’d lost hers through too many empty nights. There was no chance in Belfast of finding another man; you did not do such things when your man was in prison, a hero of the IRA. She had thought of emigrating, and she’d considered suicide, and rejected both, not so much out of fear as of indifference. By the end of that first empty year, she had donned indifference like armor. She was indifferent to Ireland, to her husband, and to life itself. Indifference was a habit like any other, with its own pleasures and comforts, and now, with Michael home after 10 years, and the whole area welcoming him as a hero, the habit remained. In some ways, it was all what remained.

“Do you want me to leave?” he asked her one chilly evening. “Do you want me to go away?” “I don’t care,” she said. “You’ll probably go away anyway. There’ll be trouble some night, and you’ll get in it, and they’ll come and lift you, and you’ll be gone. So I don’t care. I do care about the children. Nothing else.”

He went looking for work, and there was no work, and he was forced on the dole. One morning, early on, he took Brendan and Shivaun with him to visit The Scullery. He wanted to tell them about Dinny Collins, who had died while he was in prison. And he remembered Dinny saying once, “It took me so long to learn, I wish I could leave my hands to someone.” He hadn’t left his hands to anyone, of course. And when they got to where The Scullery had been, there was a row of council houses, and kids running on muddy walks, and clothes drying on lines in the back. There was nothing left of Dinny’s world, except carved stones planted in a dozen graveyards. He tried to find out what had happened to the heads of the Irish heroes, but nobody could tell him. They were gone, along with everything else that had made Dinny Collins a man and Michael Walsh a boy.

“Let’s go home,” Brendan said. They did. On weekends after that, he would take the children to see the great beauties of the north. The Glens of Antrim. The ruined stones of Dunluce Castle on the coast. The White Rocks of Portrush, with the great long swells of the Atlantic pounding in, and the stacked natural sculpture of the giant’s Causeway, and the lovely Norman castle at Carrickfergus. Brendan was usually bored, the girl full of delight. She saved a few pennies and one day in a Donegal Street bookshop, she bought him a postcard showing Rodin’s sculpture of Balzac. She never asked her father about jail, or the IRA, or the old heroes. The boy talked about nothing else.

And at night, when they were asleep, Michael would go out, to walk the Belfast streets until fatigue took him, and he could live with the enormous permanent loneliness that was his life.

In August, everything changed one final time.

“More coffee, sir?”

A pretty black waitress looked at him from across the counter. She had a coffee pot in her hand. He hesitated, glanced at his watch. Twenty more minutes.

“Yes, please,” he said. “Thank you.” How could he explain to a stranger about August 1969, in Belfast, in the northern province of Ireland? He couldn’t. It would be impossible. He would say something about the civil rights marches which had raised the temperatures all over the North. He could tell her about the rioting, the Orange mobs charging up from the Shankill, and the guns, and the fires, and how Bombay Street was burned down, and six people were killed. He could try to explain what they all thought when Jack Lynch, the Prime Minister in the Republic to the South, said he was setting up field hospitals on the border. Surely that meant the Irish Army was coming north. They were certain of that. They were coming in at last, to protect the Irish, and when they were finished the border would be a memory and Ireland finally would be united. There were men who said such things that week. But the hospitals were only hospitals. For refugees. The Irish Army did not come in. The British Army did. And there was no IRA, because they were old men now, or men like Michael Walsh, who had left all of that behind. And because there was no IRA, and no guns, people died.

In the morning, while the fires cooled on Bombay Street and the coffin makers went to work, the Provisional IRA was born.

One sullen winter night. Brendan announced that he would be going away for a few days. Some of the lads were off to Dublin to look for work. Michael Walsh went outside with the boy, and squeezed his wrist until the boy winced.

“You’re a Provo, aren’t you?” Michael said. “Somebody’s got to fight for Ireland,” the boy said.

“You won’t.”

He’d slapped the boy, and the boy had stepped back and punched him hard on the face. Michael Walsh took the blow, and then knocked his son down. By the time he helped him to his feet, Michael knew he would have to go where the boy was going. There was no choice. Brendan was a boy and knew nothing about the things that gunmen do.

“Let’s go,” he said to Brendan.

“I’m going on an operation tonight,” the boy said.

“I know,” the father said. “I’m going with you.”

They went to a flat in Andersonstown, where the others sat in awe of Michael Walsh, the hero of the ’50s, who’d given years of his life to Ireland. One of them was the young man with the long nose who’d greeted him on the day he came home from prison.

“I’m going with Brendan,” Michael said to this man.

“You’ll need a gun.”

“I’ve had them in my hands before.” The objective was a power station in the countryside. They drove out together, five of them in a car, under a starless sky. For a while, all went well, the bomb was planted, escape was certain. And then a British Land Rover came barrelling up the road. Suddenly guns were hammering everywhere, and Michael was holding Brendan, who wheezed wordlessly, and then the bomb went off, lighting up the night sky. and one of the Brits was screaming for his mother in the darkness, and they were carrying Brendan to the car, with a hole where his stomach had been. They drove madly through back roads to the border, with Brendan’s life dripping into the back seat. And all the way Michael cursed them all, and cursed himself.

“He’s gone,” the nun said at the hospital in County Cavan. “May he rest in peace.”

Rosaleen did not go to the cemetery. She said she did not want to hear the said words, the grim vows of vengeance, or see hooded men firing guns over the grave and assuring her that her son had died for Ireland. He was dead. There was nothing to be done. And when Michael came home in the afternoon from the graveyard, she told him to leave.

“Just go,” she said. “Go away and find a woman and make a life. But go. Go from Ireland. Go from me.”

“I will,” he said. “But I want you to come with me. To leave Ireland and start anew.”

“No,” she said. “You’ve got death in you, Michael Walsh. I’d look at you and see our Brendan. So just go.”

“Can I say goodbye to the wee girl?”

“No. Just go. She hardly knows you, She’ll forget soon enough. Go.”

And he went.

The airplane was on the ground. He was certain of that. The board said so. But there were so many people streaming through the doors from the customs area that he was certain he might have missed her. He saw Irish faces, and then a wave of Americans, carrying straw baskets, then more Irish faces.

And then he saw her.

She was taller than he’d imagined, with reddish-brown hair, a brown coat, high-heeled shoes. She was carrying an Aer Lingus bag. Her eyes searched the waiting crowd, her serious face blank, as if prepared for disappointment.

“Shivaun!” he called.

She turned in his direction and smiled, and he pushed through the crowd, and took her bag, and hugged her.

“Oh, Dad, I’m so glad you could come,” she said. There wasn’t much Belfast in the voice; she’d gone to school, to study art history, he knew that, to London and then to Paris. “I wasn’t certain you were still at that address, and this charter came up and I just…”

“You look swell,” he said.

“And you too.”

She turned to the porter, who had her bags on a cart, and the porter led the way outside. At the curb, Michael tipped the porter and then carried the two bags across to the parking lot. She chatted about the flight, about the food, about customs. She didn’t mention Ireland. Michael Walsh felt clumsy.

Then, as he started the engine of the car, he said: “And how’s your mother?” She was quiet for a beat, and then said: “She’s dead.”

“Good God.”

“It’s really why I came,” she said. “I didn’t know how to tell you on a telephone.” She paused. “It wasn’t too terrible. She had almost no pain. She died last Sunday and we buried her Wednesday.”

That was all. It was finished now at last. Shivaun said other things, but he didn’t hear them. He was thinking of Rosaleen. His dark Rosaleen. In a way, she too had died for Ireland, joining all the others in the endless ghostly parade of martyrs. And it had happened to her long ago. But there would be no ballad written for her to be sung by fierce young men in the smoky clubs of dark hard Northern cities. She had come only part of the way out of the stone, like a figure by Rodin, and the stone of Ireland had refused to release the rest of her.

“I hope you know,” he said quietly, “that I’m sorry for everything.” “Don’t be,” she said. And he heard Ireland enter her voice again, the soft plangent rhythm of pity and loss. “What was done was done. There’s no going back.”

“No, I guess there isn’t.”

He pulled out of the lot, and drove in silence through the airport to the Van Wyck. Shivaun watched the artifacts of the strange new world of America: cars, buses, taxis. Houses and faces. Suddenly, Michael Walsh wanted to cry, for Shivaun, and his lost son, and his dead woman; for the people of the Falls and the Shankill, too; for Provos and Brits, the living and the dead, and for Ireland. But the tears wouldn’t come. And as they came up over a rise in the highway, and saw the towers of New York rising from the sea, Michael Walsh knew, in some odd and undefined way, that he was truly free at last, and for the rest of his life. God help us all, he thought. God help us all.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the October 1986 issue of Irish America. ♦

Leave a Reply