A Californian Mission’s Irish Past

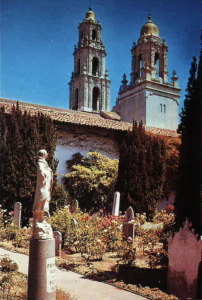

Mission Dolores, the oldest building in San Francisco, was the sixth of twenty-one missions, built under the direction of Father Junipero Serra and the Franciscan fathers, that would eventually stretch “about a hard day’s drive [ride] from one to the next,” from the Mexican border to an area north of San Francisco now known as Sonoma County.

Near a small arroyo on June 29, 1776 (five days before the signing of the Declaration of Independence) the hearty souls who accompanied the pioneer Franciscans put up fifteen tents and erected an arbor made out of foraged timber as a temporary chapel.

During the early years the mission and its surrounding inhabitants were often under the capricious control of the governments of Spain and Mexico. The bitter power struggles between the two countries–San Francisco was seen as a prized possession for both governments–thwarted much of the early good works that the padres and residents had planned. By the early 1800’s, however, a modicum of calm, peace and security had settled in the region, and the mission area became known as an entertainment center.

The start of the Gold Rush in 1849 marked the arrival of thousands of Irish immigrants. Most traveled from the slums of New York and Boston, via ship around Cape Horn. Some chose the arduous overland wagon trail.

It was during the 1850’s that Irish clergy began arriving to fill the growing needs of the Irish Catholic community. Prior to this time, few if any services were offered in English. Besides the Irish Catholics, German and Italian Catholics were likewise arriving in significant numbers.

In July of 1851, a Dublin-born priest named Eugene O’Connell accompanied a group of six nuns from Ohio, via the Panama overland trail, to Mission Dolores. Although O’Connell’s plans called for him to move on to Oregon, he was persuaded by Bishop Alemany to stay on and help the sisters establish a convent.

Eventually, in September of 1853, Father O’Connell became the resident priest of the mission. During this period, several leading Irish-born businessmen donated land, money and services to the mission in order to establish the Roman Catholic Orphan Asylum of San Francisco (built on Main Street). Included were John Sullivan, Timothy Murphy and Jasper O’Farrell – three of the most important early “Irish, San Francisco settlers.”

Years later, O’Connell would return to his seminary (All Hallows) in Dublin. There, he would often send some of his Irish Franciscan students to Mission Dolores, in an effort to continue serving his former flock.

Not everyone appreciated the increase in San Francisco’s Irish population — clergy or civilian.

The year 1854 was known as the beginning of the “mob period of San Francisco.” That was the year that the Know Nothings (or American Party) grew in size. The Know Nothings were a secret organization opposed to all foreigners, especially Catholics. And Irish Catholics were definitely on their “lowest rung of favor.”

That same year, a young priest in Ireland named Hugh Gallagher was instructed by the Vatican to enlist “several sisters from Ireland to accompany him to Mission Dolores.”

The zealous priest quickly began “recruiting.” He succeeded in selling San Francisco so well that thirteen sisters agreed to follow him to Mission Dolores. The nuns came from Middleton, County Cork, and from the convent in Kilkenny. Others would soon follow.

After sailing from Cobh, they landed in New York and then went on to San Francisco. Within two weeks of their arrival (Nov. 13, 1854), they opened their first “free school” and had over 200 children as students — many were Irish.

By December of 1854, a dozen or so other Irish nuns sailed into the bay aboard the Cortez. They had left St. Joseph’s convent in Kinsale and arrived in San Francisco to assist with the school and Mission.

Anti-Catholic hatred found expression in several newspapers of the day. Some comments were caustic and aimed at the most recent Irish arrivals, the nuns.

In one paper was quoted, “we advise the sisters to return [to Ireland], as the institutions of our Protestant and republican country are known to be obnoxious to their tastes. If this advice is not heeded, we think it is the duty of the attorney general of California to at once institute [deportation] proceedings immediately.”

This did not sit well with the Irish sisters. Sister Superior Mary Russell, from Kinsale, reacted to the published editorial by writing, “the real American Protestants have none of the bigotry you often find in Irish and English Protestants.”

During the mid 1850’s, the Know Nothings had formed a Vigilance Committee. A reinforced building near the wharf, which they called Fort Vigilance, served as their headquarters. The locals called it Fort Gunneybags, because of all the sandbags which surrounded it for protection.

The boxer “Yankee Sullivan,” was one of the many Irish who fell victim to the Vigilance Committee Born James Ambrose, in Ireland he came to America in 1841, becoming a power in politics and the ring. On losing to John Morrissey, the top man in the strong political institution, Tammany Hall, Sullivan quit New York and went to California to try his luck as a prospector. He got in difficulties there and was hounded by the Vigilance Committee. Jailed for ballot stuffing, he was found dead in his cell, apparently a victim of a Vigilante deed. On this prize-fighter’s stone appears the epitaph:

Sacred to the memory of the deceased

James Sullivan

who died by the hand of the V.C.

May 31, 1856. Aged 45 years.

James Casey also suffered at their hands. Casey, originally from Connemara had drifted to San Francisco from New York City and started his own newspaper.

The Evening Bulletin, a competing paper began publishing cruel comments regarding Casey, his newspaper and his religion. Eventually this led to a showdown between Casey and the rival publisher, James King.

Casey insisted that King retract, in writing, the vicious remarks printed about him. King refused. Casey decided to take matters into his own hands. He walked to King’s office and found him just leaving. Casey yelled out, “James King, are you armed?” When King reached under his waistcoat to pull out his derringer, Casey fired. King quickly sank to the ground. The next day he died of his wounds.

Casey was arrested but the Vigilance Committee were not about to wait for a long, drawn out trial.

On May 23, 1856, they erected a gallows outside Ft. Gunneybag. Little, if anything, could be done to stop them.

That evening, Casey was taken from the nearby jail to be hanged. He gave an eloquent speech insisting on his innocence, by way of self defense but to no avail.

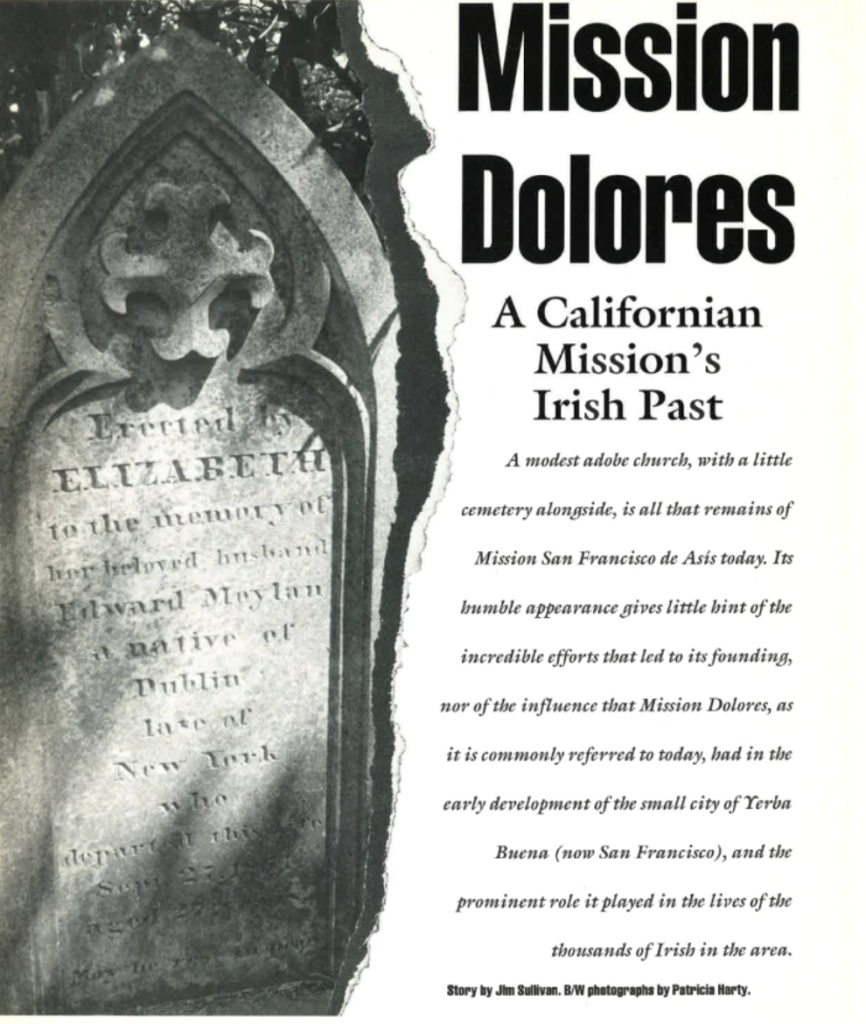

A rope was placed around his neck, the supporting boards were pulled out, and he died within minutes. The following day he was buried at Mission Dolores. On his tomb the passerby may read:

Sacred to the memory of

James P. Casey

who departed this life

May 22, 1856. Aged 27 years

May God forgive my Persecutors

Requiescat in Pace.

Walking around to the west side, the visitor continues to read:

Erected by the members of Crescent Engine Company No. 10 as a tribute of respect and esteem.

This chilling event was one of the most ugly in San Francisco’s history. Ironically, the hangings so infuriated the peaceful citizens not affiliated with the Vigilance Committee that within a short period, the organization lost its support and slowly evaporated.

Mission Dolores continued to function as the spiritual and social center for San Francisco’s Catholics for years. Although many cathedrals and parishes were eventually built, the mission was always held close to its parishioners’ hearts.

The original adobe at the mission was so well constructed that it was spared damage during the terrible 1906 earthquake and fire which followed. During that event, over 500 city blocks were lost, which represented 28, 188 separate buildings.

Today Mission Dolores is open to the public daily, from 9 am to 4 pm. Those who have the time (and a healthy imagination) should definitely take the time to walk the mission grounds — and its cemetery. Simply by reading the Irish surnames and dates on the headstones, one will come to appreciate the role the Irish played in early San Francisco. For:

“When each of county of Old Ireland

Sought a judgment day’s position,

It chose slightly south of Market

And a little west of Mission.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the January/February 1994 issue of Irish America. ♦

Leave a Reply