As British Prime Minister John Major and Taoiseach Albert Reynolds announced their historic “Joint Declaration for Peace” in Northern Ireland on December 15, the vital question was whether the new document would be sufficient to launch a real peace process or whether it would end up as just another failed initiative.

An historic opportunity for peace in our time or just another sideward step in an increasingly difficult process which has yielded little change in 25 years of violence in Northern Ireland?

Those were the two polar positions following the release of the Joint Declaration on Northern Ireland, signed by the British and Irish Prime Ministers and published on December 15 amid a worldwide surge of support for the initiative, including an effusive welcome from President Clinton.

“The joint declaration reflects the yearning for peace that is shared by all traditions in Ireland and creates an historic opportunity to end the tragic cycle of bloodshed,” said Clinton.

At the other extreme in the U.S. was the reaction of Irish Northern Aid leader Martin Galvin who stated on behalf of the Irish republican support group “Today’s ballyhooed peace declaration is not a step towards peace but a disappointing recipe for further bloodshed in Ireland.”

Galvin’s caveat, however, was almost drowned out in the rush to hail the declaration, a process greatly aided by a massive public relations offensive by the two governments on both sides of the Atlantic. The New York Times, the London Times and almost every newspaper of substance hailed the new document as the best opportunity for peace in the quarter century since “The Long War” as this latest phase of the “Troubles” has now come to be known, began.

In Ireland, Seamus Mallon, Deputy Leader of the nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) stated that if the sentiments contained in paragraph four of the document had been contained in the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 which established partition there would never have been the outbreak of civil war in the South or the continued “Troubles” in the North. (Paragraph Four states in part that the British have no long term interest in Ireland and would establish a united Ireland at a future date if both sides of the island agreed.)

The renewed hopes of a generation for peace rested on a seven page closely typed document which contained 12 numbered paragraphs, all dealing with the Northern Ireland problem which was described as “a masterpiece of ambiguity” by one commentator. (See sidebar).

At the heart of the document was an attempt to “square the circle” to take the two competing traditions, the Ulster Unionist, which wants to remain part of Britain, and the Irish nationalist which wants a united Ireland in some form, and hammer out a document acceptable to both sides.

In the end, the document takes and gives to both. For the Unionists there is the restatement that as long as they are in the majority in Northern Ireland they can vote to stay part of Britain. For the nationalists, there was the reiteration that Britain was now truly neutral and had no “selfish’ interest in remaining in Ireland and also that they would not stand in the way of a United Ireland if one was voted for separately on both sides of the border.

For the Unionists there was also a later sop: just after the agreement it was announced in the House of Commons that a Select Committee would be established for Northern Ireland, a move long opposed by Nationalists. The committee, which will recommend legislation and hold hearings similar to a House or Senate committee in the U.S., will be Unionist dominated because they have larger numbers in the Westminster parliament.

But the Unionists clearly have reasons to fear the Joint Declaration in real terms also. Demographic changes since partition in 1921 now show that Catholics are close to 43 percent of the population, up from 38 percent just 10 years ago. If that shift were to continue then the Major declaration that Northern Ireland would remain British only as long as the majority voted that way could quickly turn out to be a Trojan horse.

Despite the worldwide acclaim for the document, even those most enthused by its provisions doubted that it would have any long term impact unless it had the effect of bringing the violence in Northern Ireland to an end before new negotiations began. Over 3,100 have been killed in the longest running conflict in Europe and the continuation of violence into a new quarter century was a depressing reality for all would-be peacemakers. A cessation of violence, everyone agreed, was a first principle for progress.

The British had clearly believed this to be the case. Before the Joint Declaration was issued it became public that they had been holding secret negotiations with the IRA going as far back as 1990 perhaps, to seek ways to end the stalemate.

These revelations, despite years of denials that any such contacts were taking place, incensed the Unionist parties in Northern Ireland, but remarkably were welcomed in Britain, where Prime Minister Major was hailed in almost Churchillian terms as a risktaker for peace.

The British, however, had broken off the substantive element of the talks earlier this year, when the Prime Minister’s majority in the House of Commons was threatened and he needed Ulster Unionists votes to ensure he stayed in power. Now their new initiative with the Irish government was an attempt to solve the Northern Ireland problem by moving both extremes towards an agreed center.

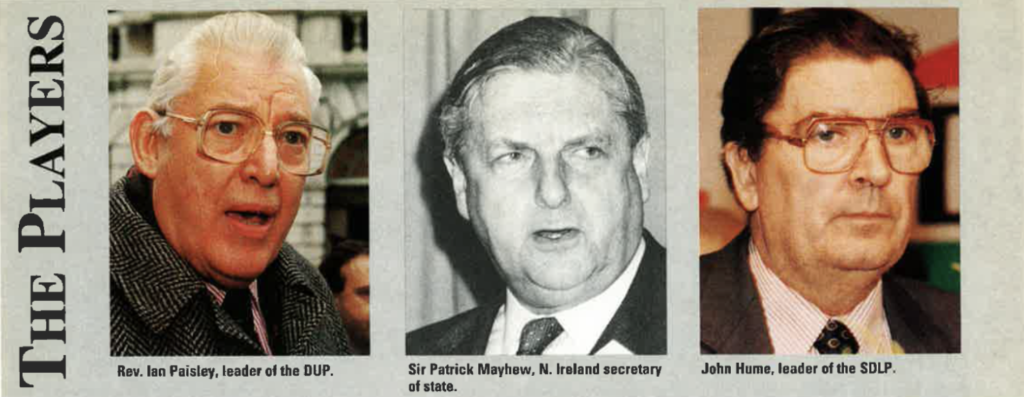

It still remains to be seen whether it will succeed. Loyalist paramilitaries have killed more people in 1993 than the IRA and have embarked on a particularly vicious sectarian campaign throughout the latter half of the year. Following the Joint Declaration, The Combined Loyalist Command made up of the Ulster Freedom Fighters, a code name for the Ulster Defense Association and the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) stated they were studying the document. However, the Reverend Ian Paisley, whose party, the Democratic Unionists, represents much hard-line Loyalist opinion, thundered that the agreement had “sold Ulster to buy off the fiendish Republican scum” (prompting a reporter from the Daily Mirror to ask him, tongue in cheek, “so it’s a cautious welcome then?”)

The response from Sinn Fein, the political wing of the IRA, was far more circumspect. “Proper and full consideration requires, of necessity, that these deliberations [on the Joint Declaration] will take some time” said the organization’s president Gerry Adams.

Adams’ muted response was not unexpected, after all he had played a large role in the two governments coming together as a matter of urgency to deal with the issue of Northern Ireland.

Throughout 1993 and before, he and John Hume, leader of the SDLP, had propelled the peace debate onto the front pages by beginning a series of meetings aimed at a joint proposal for peace. In the frozen tundra of Northern Irish politics, the sight of the two arch rivals for the nationalist vote agreeing on a consensus approach had the effect of a melting ice cap and underlined the need for a new peace process after twenty-five years of war. The underlying reality was that both parties had changed some of their fundamental positions to arrive at their consensus.

The Shift in Sinn Fein

The shifting ground in Northern Ireland is nowhere more exhibited than in the political development of Sinn Fein, for long the mere mouthpiece of the IRA with an irredentist “Brits Out” view. In recent times, however, Sinn Fein has begun a long political journey towards a level of sophistication which ensures it is now a key player in any peace talks.

The political path was sparked by the 1981 hunger strikes which ended in the death of Bobby Sands and nine others, and resulted in spectacular electoral victories in subsequent elections for Sinn Fein. Currently, the party is the largest on Belfast City Council for instance, and represents up to 40 percent of the nationalist vote in Northern Ireland.

The new sophistication is personified by the party leader Gerry Adams, (44) himself a former IRA operative, who has now spent over 20 years in senior leadership in the movement. Around him are a group of Northern Republicans of similar mien who wrested control of the organization away from the Dublin-based leadership in the mid 1970s after a disastrous cease-fire.

Early in this decade, the irredentist hardline began to give way to a more pragmatic view of the Northern conflict. The Republican leadership clearly recognized, as the British Army do, that there can be no outright victor in the military battle between the IRA and the British.

Equally there was an acceptance that the Unionist population could not be coerced into a United Ireland and that while they could not continue to exercise a veto over such a development, their concerns would have to be fully reflected in any new arrangements.

The Sinn Fein leadership clearly began to see the conflict as resolving itself in a series of incremental steps rather than winning the united Ireland overnight. In that respect their policy now came closer to the SDLP one which, after several setbacks, had actually hardened from a contemplation of an internal settlement to the necessity for an All Ireland dimension. Thus, John Hume and Adams realizing the new potential for agreement sat down together.

Their joint statement, known as the Hume/Adams agreement was announced, causing a wave of media speculation and analysis and heralding a new reality in Northern Ireland.

The effect of their joint statement in the Irish Republic was especially felt. Due to censorship restrictions, the shift in Sinn Fein thinking had been completely missed by large sections of the Irish media who were thunderstruck by the agreement. (They were to be thunderstruck again a few weeks later when details of the British/IRA contacts became public.)

Details of what they agreed were not released, and have not been at the time of going to press, but their document contained the blueprint for the steps necessary for a cessation of violence and a settlement of the conflict.

At the same time, Taoiseach Albert Reynolds, who had surprised many Southern observers by his firm commitment since taking office to seeking peace in Northern Ireland. His stated priority when assuming office as head of a Fianna Fail/Labour Party coalition was to do so, but it was dismissed by much of the media at the time as mere lip service to a token ideal.

Reynolds, however, was for real, as was his Deputy Prime Minister Dick Spring, leader of the Labour Party and the son of an IRA veteran, who had long experience in the area, as he occupied the same position in 1985 when he was Deputy Leader to Garret FitzGerald during the signing of the Anglo-Irish Agreement with Margaret Thatcher.

Reynolds also had one ace card denied many of his predecessors, a cordial and friendly relationship with his opposite number, John Major, who was from a similar “up by the bootstraps” background and pragmatic outlook on Northern Ireland.

Throughout 1993 both men worked together on the issue, and their discussions assumed an almost frenetic pace once the Hume/Adams talks became public knowledge. The fruits of their labor, the Joint Declaration, was drafted almost around the clock by senior officials of both governments and was only finally signed off on hours before their final meeting.

What the Future Holds

THE key question on whether the IRA and the Loyalist paramilitaries will cease their campaigns in 1994 in response to the Joint Declaration will likely remain unanswered for the immediate future as both carefully study the Joint Declaration.

What is clear is that the narrow ground of Northern Ireland politics has been rent apart by recent developments, of which the Joint Declaration and the Hume/Adams accord are the major ones.

The British can now never go back to “no talking to terrorists.” The IRA have moved far from the simplistic “Brits Out.” The Loyalists now know the British will abandon them if the demographic numbers continue to work against them, while the Irish government is finally engaged after a long period of adopting a “hands off” approach to Northern Ireland.

The new equations after decades of arid and ultimately predictable debate where no side conceded anything means a new set of realities for all the players. However, whether the shifting sands arising out of the new reality can become the high ground of a long-term solution acceptable to all, remains to be seen.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the January/February 1994 issue of Irish America. ♦

Leave a Reply