The great famine, the legacy of Wolfe Tone and the nature of the 1798 rebellion, Patrick Pearse’s psychological stability, and whether the gallant fight for freedom provides a thematic unity to Irish history: These and many other questions have been thrown open by “Revisionists” who regard “traditional” Irish history as a jumble of silly sentiments, wishful thinking, and distorted “facts.” Kelly and Kerry Candaele interviewed historians on both sides of the debate.

In cafes and pubs close to Trinity University in the center of Dublin, students talk with increasing skepticism about their national heroes. “Tone was an opportunist who couldn’t even speak the language of those he was trying to liberate.” “Pearse was neurotic and probably a homosexual, consumed by a messianic Christ complex.” “During the famine of the 1840s the British did all they could given the resources available to them and the magnitude of the crisis.” “The 1916 Easter rebellion was an ill conceived minority led revolt that only serves to justify current IRA terrorism.” This is revisionist history made concrete, scholarly discourse distilled and emptied into the streets, capturing the hearts and minds of Ireland’s educated young. And there are a lot of people who don’t like it.

Those who defend the revisionist historians argue they are merely writing a more sophisticated and mature version of the Irish past, one suited to a country that must become less insular, less protected, more European. Other scholars and critics believe a more serious political agenda is hidden beneath the veneer of academic “objectivity.”

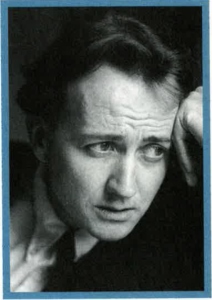

One of the major re-interpeters of Irish history is Roy Foster, the Carroll Professor of Irish History at the University of Oxford. When he speaks about the “revisionist” controversy he does so with a barely concealed anger, the product of his frequent vitriolic combat with other academics and writers that has often turned personal.

Foster’s six hundred page book Modern Ireland 1600-1972 was hailed as “A work of gigantic importance” by the Irish Times when it was first published in 1989. Modern Ireland sold close to 40,000 copies in Ireland and stayed atop the best seller list for six months. Foster wrote the book in an attempt to rescue Irish history from what he calls the “Manichaean logic of the old ‘Story of Ireland view’ with a beginning, a middle and what appeared to be a triumphant end,” the creation of the Irish Republic.

Foster retains, he says, a “robust skepticism about the pieties of Irish nationalist history,” and a reluctance to “blame every unwelcome development in Irish history on British malevolence.”

Modern Ireland, a touchstone for attacks on the so-called “revisionist” historians, begins in 1600 with the forging of the Protestant plantation in Ulster and ends with the closing down of the Northern Irish government of Stormont in 1972.

Sardonic and skeptical observations run throughout Foster’s book. Absent are heroic descriptions of the “bold Fenian men” or the “great martyrs of 1916,” portraits that he believes have contributed to a romantically distorted image of the Irish past and worse, an unwarranted hatred of England. What remains are historical actors who were often confused and animated by disparate economic, political and social agendas. Foster places local and regional grievances and quarrels at the center of Ireland’s contentious past, conflicts that he believes are largely unrelated to English malevolence.

One of Foster’s most incisive critics is Brenden Bradshaw, a Catholic priest and history professor at Queens College, Cambridge. He is Foster’s scholarly nemesis in academic journals, the popular press and in public forums.

The fight has become so virulent between the two that Foster has accused Bradshaw of being a fellow traveler of Provisional Irish Republican Army terrorists. In Bradshaw’s view, Foster is an insidious maestro, the leader of a revisionist agenda that conspires to “remove the pain from Irish history,” through the “distorting devices of academic discourse, thereby cerebralizing and desensitizing the trauma of Irish history.”

If Foster sees himself as writing a more “objective” history, Bradshaw condemns the revisionists’ “invincible skepticism” as an historical approach that leads to a detached, jaundiced, and cynical view, robbing Irish history of its “grandeur, nobility, tragedy and pain.”

Bradshaw argues that revisionist historians have attempted to dismiss Irish national consciousness, the sense of belonging to a country called Ireland with a distinctive culture, as a romantic fiction. In public forums and academic journals, anywhere he can find an audience, Bradshaw attacks the revisionists for trying to “depopulate Irish history of heroic figures, struggling in the cause of national liberation.”

The “heroic figures” Bradshaw refers to are well known to every Irish man and women — Wolf Tone, Robert Emmet, Daniel O’Connell, Charles Stewart Parnell. “If you place these people in the dock as the revisionists have done, and conduct the case for the prosecution, invariably they emerge discredited,” Bradshaw declares.

One of the liveliest debates is over the life and legacy of revolutionary leader Patrick Pearse. Long after his death by a British firing squad for his role as a primary architect of the Easter uprising of 1916, Pearse remained virtually a canonized saint of Irish political history.

If you drive through the Catholic “bogside” of Derry or the Ardoyn area of Belfast in Northern Ireland you still feel Pearse’s presence. His famous oration at the grave of Fenian leader O’Donovan Rossa in 1915: “They think they have pacified half of us and intimidated the other half . . . the fools, the fools, they have left us our Fenian dead, and while Ireland holds these graves, Ireland unfree shall never be at peace” adorns the walls in these Republican enclaves–a daily reminder of the power Pearse and his martyrdom still has to inspire a new generation of IRA soldiers.

In a biography of Pearse by historian Ruth Dudley Edwards, Patrick Pearse-The Triumph of Failure, a book widely praised and condemned, Pearse emerges as a deeply flawed and politically dangerous personality.

Edwards portrays Pearse as a naive political romantic with an obsession for a martyrdom that could only be achieved through an heroic “blood sacrifice,” a bloody sacrifice that would cleanse and redeem the Irish nation. He glorified war, she argues, and was so captured by his own vanity that he believed that the small cadre of revolutionaries he led embodied the will of the Irish nation.

On Pearse’s role in the 1916 uprising Edwards declares that he was part of a “despotic tradition” . . . an “exponent of a romantic morality which sanctioned the sacrifice of self and others in the pursuit of self-realization.” She concludes that Pearse “wrote, acted and died for a people that did not exist. He distorted into his own image the ordinary people of Ireland.” Edwards, in what her critics call a typical revisionist claim, regards her portrayal of Pearse as a more “objective” view of his legacy, less encumbered by the rosy romanticism of previous biographers.

In a defense of Pearse, J.J. Lee, Professor of Irish History at University College Cork, in the collection of essays Revising the Rising, partially exculpates Pearse by placing him in a pre-World War I environment gone mad, where eminent writers and poets throughout Europe rhapsodized about the heroic and redemptive qualities of war. A number of historians have pointed out that when World War I finally came, for two years or more reporters and politicians represented the carnage as “exciting, fulfilling, glorious, holy, noble, beautiful, gay, and, all in all, great fun.” Pearse’s rhetoric was entirely in keeping with widely held beliefs.

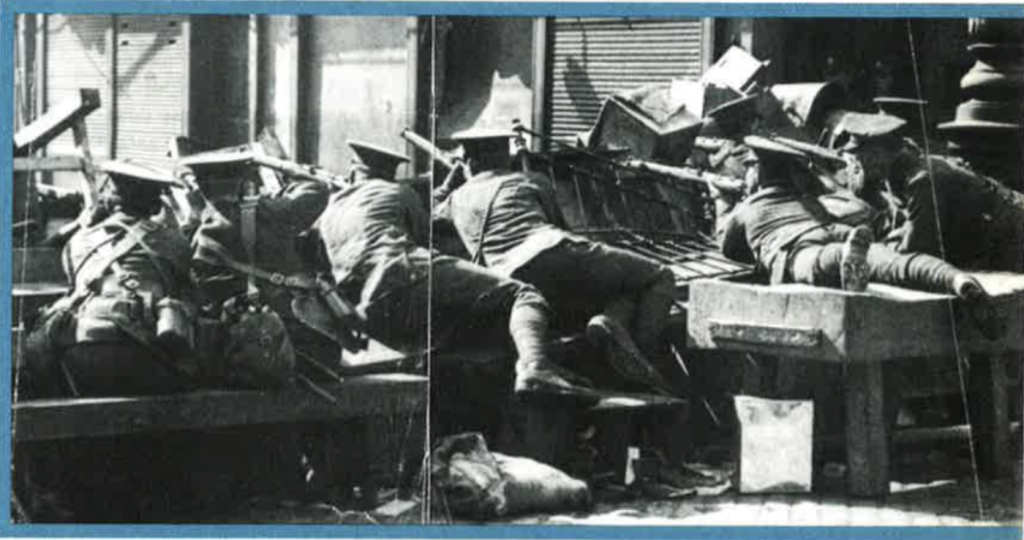

Lee also contrasts Pearse’s occasional shrill pronouncements with the actions of a rather pacific personality. Lee points out that Pearse and the other rebels wanted and planned for more than a “sacrificial” blood letting during Easter 1916. They wanted victory and did their best to acquire the arms necessary to sustain broad military action. And Pearse’s bellicose rhetoric belied his reluctance when it came to meting out violence himself. He opposed corporal punishment at St. Enda’s, the school he ran, and he was persuaded to surrender to British authorities after witnessing the killing of three civilians, ending the Easter rising.

For his part, Bradshaw claims that Edwards has created a Pearse who “emerges as pathetic, incompetent and neurotic.” “You can’t reduce a giant to the dimensions of a dwarf. He was a man who at the age of eighteen was invited onto the National Council of the most flourishing national, cultural movement of the time, the Gaelic League. He was a man who the hard headed Irish Republican Brotherhood felt in the end could actually be the leader of this revolution they were proposing to launch. You want to see Pearse as he really was, but you don’t do that by putting him into the dock, chopping away until he is naked.”

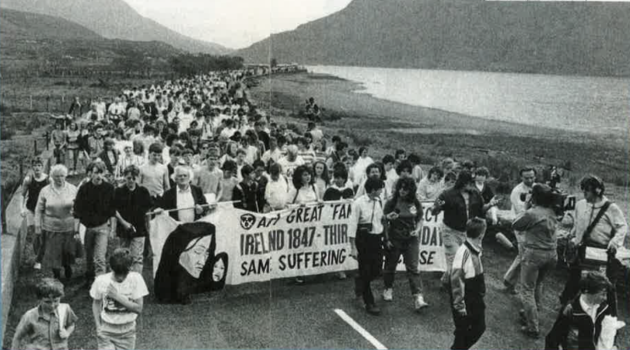

The Irish Famine of the mid and late 1840’s is another controversial touchstone for the rewriting of Irish history. For many Irish the Famine conveys the tragedy and pain that Jews associate with the Holocaust. One statistic conveys why the famine is seared in the Irish memory. The population of Ireland in 1840 was 8,200,000. By 1911, through famine deaths and emigration, the population was decimated, reduced to 4,400,000. The rest of the world received the Irish diaspora, a whole generation of talent and energy. Ireland received a cruel lesson in the consequences of imperial domination.

Economic historian Cormac O’Grada, one of Ireland’s leading scholars on the famine, argues that the famine was “the most important event in Irish history in the past two hundred years.” Until recently, O’Grada claims, historians have been reluctant to write about the famine. The potentially divisive nature of that devastating history kept many historians from scholarly research. Remarkably, discussion of the famine was even taken off the school curriculum for some time. O’Grada points out that many government officials felt “if we tell them [students] what happened during the famine they will all join the Irish Republican Army.”

Again Foster is a lightning rod for controversy. Foster’s account of the famine in Modern Ireland does not contain detailed descriptions of starving Irish peasants, their teeth stained green from eating grass or vivid scenes of dying women and children. These powerful and compelling images of death, the so-called “emotive” picture of the famine, are found throughout the best selling Irish history book of all time, Cecil Woodham Smith’s The Great Hunger.

Foster writes in a style he describes as “if not objective, at least dispassionate,” and finds it “very dreary to get into morally beating one’s breast, weeping, pointing the finger at the iniquitous British oppressor.” He also downplays the famine as a watershed in Irish economic history, tracing large scale emigration, changing farming structures and demographic decline to well before the famine. Foster lets his computers do his breast beating; statistics shed no tears; emigration patterns are just that, lines on a page, flow charts that don’t cry out in harsh voices.

On the critical question of “what could have been done” to alleviate the starving there is still a wide divergence. Mary Daley, another historian sometimes grouped into the “revisionist” school, concludes generously at the end of an exhaustive narrative of the complexities of famine in her book, The Famine in Ireland, that “it remains difficult to conclusively argue that a greater sympathy with the Irish case would have automatically guaranteed a dramatically reduced mortality.” She adds that “it does not appear appropriate to pronounce in an unduly critical fashion on the limitations of previous generations.”

Daley’s is the language of academic fright, says O’Grada. It is a discourse frozen with hesitating self-doubt, an analysis he regards as “too ready to make excuses” for a British administration that was “doctrinaire and heartless.”

Daley grants an a priori absolution to the British, never asking why a laissez faire economic philosophy existed in the first place and who benefited from that ideological hegemony. Racism against the Irish never enters the picture.

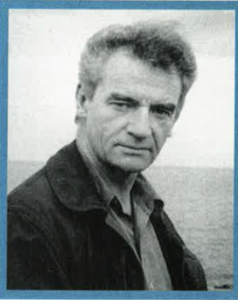

Surprisingly, non-Irish historians have done much of the recent major research on the famine. American historian James Donnelly is not as filled with doubt as his more “objective” Irish colleagues. Nor is he as kind to the British government of the 1840s.

Donnelly, Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin, believes that history is made by people, not mysterious “forces” with inevitable trajectories. And people with power in the mid 1840’s made decisions that had profound consequences for famine-plagued Ireland.

In a paper presented at a conference at Villanova University in anticipation of the one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the famine Donnelly put his question directly. “What is the extent to which the British government was responsible for mass death and mass emigration because of the policies which it did or did not pursue?”

Donnelly focused on the writings of John Mitchell, the 19th century Irish revolutionary nationalist who excoriated the British government relief measures of the time as “contrivances for slaughter.” Mitchell’s 1861 book The Last Conquest of Ireland profoundly influenced the attitudes of generations of Irish toward the British. Mitchell emphatically asserted that “a million and a half men, women and children were carefully, prudently, and peacefully slain by the English government. They died of hunger in the midst of abundance which their own hands created.”

Mitchell’s charges contain a “core of truth,” according to Donnelly who points out that in 1846 the Irish grain harvest was allowed to be exported with “murderous effects.” Foster calls the exporting of food an “economic irrelevancy.” British policy from mid 1847 on insisted that reliance for funding famine relief be placed in Ireland rather than in the United Kingdom as a whole. And the notorious “Gregory clause” of the Irish Poor Law denied relief to anyone possessing more than a quarter acre of land, encouraging land clearance and emigration. This act, which only two Irish members of the House of Commons voted against, “was directly responsible for thousands of deaths,” according to O’Grada.

The British government spent nine and a half million pounds in Ireland during the famine. A few years earlier the Whitehall government gave West Indian slave owners twenty million pounds as compensation for slave emancipation. Shortly after the famine the British government spent seventy million pounds in the futile Crimean War, a fact that O’Grada finds “neither fanciful nor anachronistic.”

Nineteenth century Britain was in the doctrinal grip of laissezfaire economics, a theory that propounded the principle that interfering with the beneficent effects of “free markets” would only have exacerbated an already dire situation.

Charles Trevelyan, the Undersecretary of the Treasury responsible for famine relief, articulated this deadly Malthusian logic. He described the famine as “a direct stroke of an all-wise and all merciful Providence,” declaring the famine “the sharp but effectual remedy by which the cure is likely to be effected.” If Trevelyan saw the invisible hand of Providence in the famine, the Irish saw an all too visible race hatred.

O’Grada, who describes himself as a “post-revisionist” historian, someone not “obsessed by nationalist or antinationalist historiography,” concludes his summary of the famine with an attempt at balance. “Nobody wanted the extirpation of the Irish race,” he writes. “The difficulties of trying to keep down deaths were enormous. Had the crop failed only in 1845 we wouldn’t be writing about the famine now. I don’t accuse the British government of bad intentions. They thought they were doing the right thing, but a more generous government might have prevented the deaths of hundreds of thousands more.”

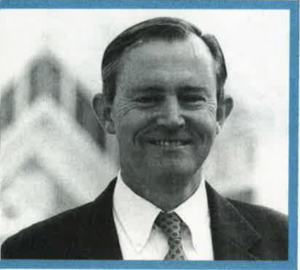

Leading the charge of “attitudinal revision” of the 1916 Rising is Conor Cruise O’Brien. O’Brien scathingly refers to Easter 1916 as a minority led “putsch with no pretense at popular support at all.” In a recent interview he trenchantly argued that the current Provisional IRA are indeed the inheritors of the 1916 rebel legacy, a historical myopia that they use to justify an armed struggle that is clearly without popular support.

“The Provos derive their sacred authority from their supposedly superior fidelity to the ideas of 1916 and to the martyrs of 1916. They regard that as giving them a mandate irrespective of any democratic process. Whether they are a minority or not has nothing to do with it. If they represent the tradition of 1916, that tradition is sacred. And you had better get out of their way because they have a mandate to kill you.” He added that “those whose political and moral capital is wrapped up in the cult of 1916 naturally bitterly resent revisionism.”

O’Brien’s book, States of Ireland (1972), helped shape a popular consensus about the intractable nature of the conflict in Northern Ireland and the nature of the modern IRA. He argued that the antagonism and intransigence of Northern Unionist opposition to joining the South were based on profound historical, cultural and religious experiences that would not disappear if the British pulled out. The violence that would follow a British withdrawal from Ulster would make the conflict in Yugoslavia look like a Sunday picnic.

For O’Brien, the conflicting signals that the Republic’s political leadership sent North on the issue of partition, the South continuing to make territorial claims on the North, was dangerous and unrealistic. O’Brien felt that the slightest encouragement from the South meant continued intransigence and violence by the Provisional IRA.

The first full scale “moral” re-interpretation of the legacy of the Rising was written by Father Francis Shaw fifty years after the rebellion in 1966, but was not published until 1972. The editors of the magazine it was written for felt its iconoclastic theme and argument was “untimely.” (The fiftieth anniversary commemoration in Dublin was a much more triumphant affair than the seventy-fifth, which was barely noticed in 1991).

Shaw’s article, The Canon of Irish History -A Challenge, turned the triumphant nationalist interpretation of the Rising on its head. Shaw saw the rebellion as more an anti-democratic putsch than a popular revolt. He also argued that the resort to violence ended the possibility for a peaceful solution to the crisis surrounding the issue of partition between Ulster and the South and plunged the country into civil war.

Referring to the rebels’ justification for the Rising Shaw wrote:

“In effect it teaches that only the Fenians and the separatists had the good of their country at heart, that all others were either deluded or in one degree or another sold out to the enemy. This canon moulds the broad course of Irish history to a narrow preconceived pattern; it tells a story which is false and without foundation.”

The debate surrounding the publication of Shaw’s and O’Brien’s works created what one observer called “a new consensus” in the media whereby “academics could now write entire narratives of Irish history which contain no reference whatever to either “colonialism” or “imperialism.” Years ago, Easter Monday was a sacred day, remembered and celebrated triumphantly much like an American Fourth of July. But on Easter Sunday in 1991, the 75th anniversary of the Rising, a television reporter asked then Prime Minister Charles Haughy why he choose to hold a commemoration at all.

Foster feels right at home with that new consensus. In his interpretation of 1916 he agrees that he “did produce a fairly revisionist line,” regarding the Rising as not the inevitable climax of years of unbearable oppression, but a contingent response to the immediate circumstances generated by the crucible of World War I.

The First World War, he writes “should be seen as one of the most decisive events in modern Irish history. It tragically defused the Ulster situation, it put Home Rule (which was passed out of Parliament in 1914) on ice and it created the rationale for an Irish Republican Brotherhood rebellion.”

J.J. Lee, in his prize winning book Ireland 1912-1985, challenges one of revisionists’ main contentions that the Easter Rising was universally unpopular.

Lee points out that very little concrete information was available to the public during the week of the rebellion and that the major papers that did report on the events painted the rebels as sympathetic to a German invasion of Ireland or as “socialist” plotters. The latter theory derived from the fact that prominent trade unionist and socialist theorist James Connolly was one of the rebel leaders fighting in the General Post Office.

Lee concludes from his research that “there was also much sympathy for the rebels, at least while there appeared to be some hope of success.” As people gained more accurate information about the motives and aims of the rebels, Lee argues, “their reactions were mingled feelings of despair at the folly of the rebels, pride in their gallantry, and contempt for their gaolors.”

Lee adds that among the leaders were more than romantic visionaries. Three future Prime Ministers fought against the mightiest army of that time. The dynamic Michael Collins who would later lead a guerilla war against Britain, fought bravely in the Dublin Post Office, and Lee even describes Pearse as a “major educational thinker.”

In a kind of posthumous validation of the rebels’ agenda the 1918 election to the English Parliament from Ireland swept away the moderate Irish Parliamentary Party as Sinn Fein, the nationalist insurgents, took 73 seats with 65 percent of the votes cast in the 26 counties that would later make up the Southern Republic.

Brenden Bradshaw draws a reluctant and tragic lesson from the Rising and his overall reading of Irish history. Bradshaw calls himself a pacifist but ironically concludes that “the British government right through Irish history has responded to nothing but violence, the bomb and the bullet,” and “had the Rising not taken place the whole movement for national self determination would have been put on permanent hold.”

If Foster and his defenders are comfortable with the “new consensus” Kevin Whelan is not. Whelan, historian of the 1798 uprising of the United Irishmen, and Research Scholar at the Royal Irish Academy in Dublin, believes the symbiotic relationship between revisionist scholars, the popular media and the political establishment has become way too convenient.

Whelan singles out O’Brien and the newspaper the Irish Times as “that segment of Irish opinion that wants to use that sort of history not for historical purposes but for some kind of present day political perspective.”

He echoes Bradshaw’s contempt for the revisionists’ “non-judgemental approach” to the British role in Ireland which “contrasts starkly with their severely judgemental approach to Irish nationalism.” This “cosy, cloying consensus,” Whelan argues, “smooths the way for an acceptance of the modern British version of their role in contemporary Ireland as neutral peacekeepers between two warring tribes.” While an older Irish historian once asked in a moment of sardonic reflection if the Irish do not suffer from a “surfeit of history,” Whelan wants more history to be researched and written, but of a certain type. He urges historians to move beyond political history and the “national question” and take up neglected issues of class division, women’s history and attempts at recreating the “popular mind” of the Irish people. Taking a closer look at myths, legends, music and other aspects of popular culture is Whelan’s agenda for penetrating history from the bottom.

The writing of history is “a kind of fiction or story” derived from the time in which it is written that retrospectively imposes a coherence on the ragged contours of the past, says Seamus Deane, a leading Irish literary critic and main editor of the three volume Field Day Anthology of Irish Literature. For Deane, schooled in the arcane philosophical thicket of literary theory, the revisionist “story” is as much an imposed overarching “metanarrative” as the older nationalist story. “Foster’s Modern Ireland is the summary version of revisionism. . . historical writing that actually reproduces the propaganda of the Southern government in relation to the Northern crisis.” “It’s as much a metanarrative as the nationalism it’s trying to replace.”

In summing up the revisionist debate Deane asks a completely different kind of question about Ireland’s understanding of its past. “The question is not whether nationalist historians are ‘right’ and revisionists ‘wrong’ but a matter of living between the possibility of being liberated by your capacity to interpret the past, and the situation that often exists in colonial countries, being fixed and stereotyped within a single version of the past whether it’s of the revisionist or nationalist kind.”

Kelly Candaele is a film maker and writer living in Los Angeles. Kerry Candaele is the Richard Hofstadter Fellow in History at Columbia University in New York.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the July/August 1994 issue of Irish America. ♦

Leave a Reply