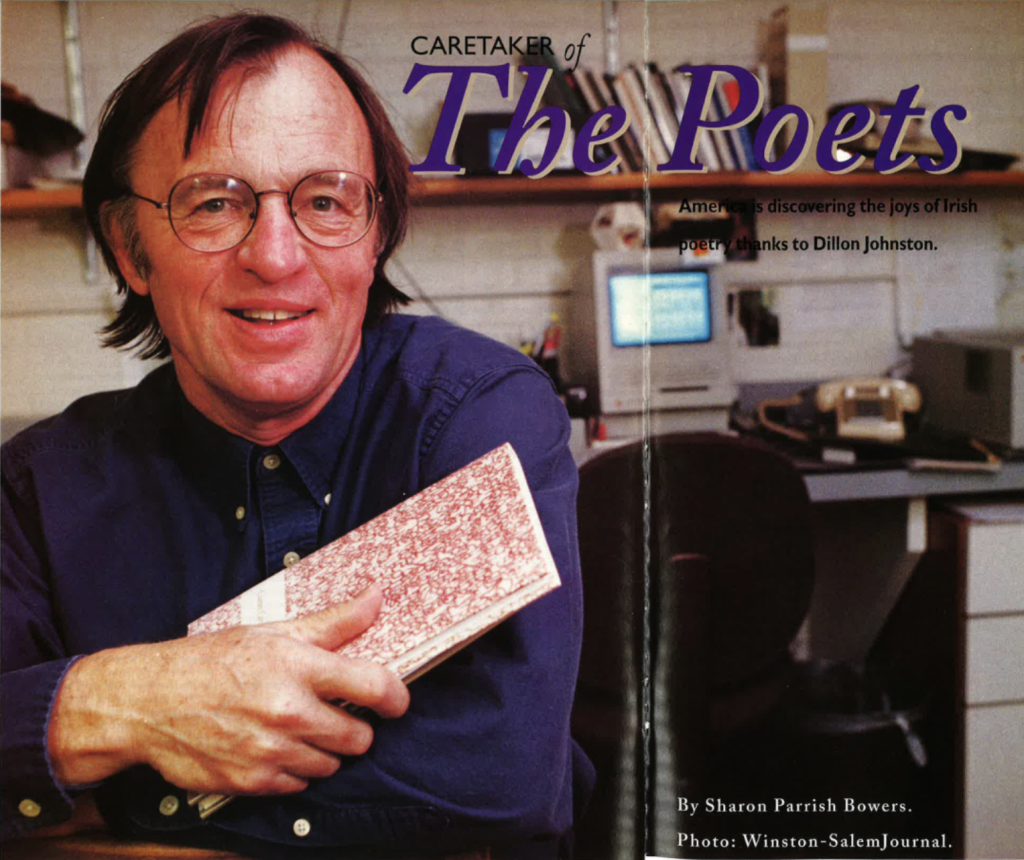

America is discovering the joys of Irish poetry thanks to Dillon Johnston.

Set leisurely atop undulating manicured lawns are the neat brick buildings and magnolia trees of Wake Forest University, a private college in Winston-Salem, N.C., Baptist-founded, home of the Demon Deacons. Well-dressed and tanned students stroll with their bookbags on the plush grass of the main quadrangle and sit reading on the sunny steps of the new library. It is American academia at its most picturesque — small and traditional but with a strong M.B.A. program.

Readers around the world, however, know and respect this place as a raging hotbed of cutting-edge Irish poetry. For this is the home of Wake Forest University Press, in whose fertile soil the best Irish poets of a generation have found nourishment, succor and award-winning editions of their books.

Tending this thriving literary garden is Dillon Johnston, professor of English at Wake and director of the Press, whose mild manner and hesitant smile belie a white-hot passion for poetry. Such a passion, in fact, that when he was writing an article on Irish poets in 1975 and found hardly any of their books, he decided to remedy the situation himself by establishing Wake Forest University Press.

“I didn’t know that it was a life’s indenture,” Johnston said, smiling, on a recent visit to New York to launch the Press’s latest book, Ciaran Carson’s First Language. “I just thought it was something to be done.”

He credits Liam Miller, who ran Dolmen Press, Ireland’s only poetry press at that time, with being “terribly encouraging,” as well as Edwin G. Wilson, former provost of Wake, who enthusiastically accepted Johnston’s initial proposal to establish the Press. And Johnston is characteristically modest about his own part in the process, which included nosing out young and unknown Irish poets.

“I just read everybody that was writing, and made a list of people that I would want to publish. And for a while, we actually achieved that list, excepting Heaney,” who was already published here by Oxford University Press.

Already having American publishers did not stop some poets from jumping on the bandwagon, however, including Thomas Kinsella, Derek Mahon and Richard Murphy, who at different times left major houses to work with the young Press. In the case of Ciaran Carson, who had until then published only individual poems, Johnston helped to establish him in his own country by proposing a concurrent edition with Blackstaff Press in Belfast, and the Press published Paul Muldoon before he had even left college.

The Press now publishes many of the same poets as Gallery Press, Ireland’s foremost poetry house, directed by Peter Fallon. To ensure maximum exposure on both sides of the ocean, many poets come to the U.S. for reading tours, largely arranged by Candide Jones, the business manager for Wake Forest University Press.

The Press has brought over a number of Irish poets for the first time, including Ciaran Carson, Paul Muldoon, Michael Longley and Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin. “Candide’s gotten to be very good at organizing these tours — you know, some poets never get home,” Johnston said, including Muldoon, who teaches at Princeton, and John Montague, who holds a distinguished professorship in the New York Writers’ Institute in Albany.

“That’s a great way for people to encounter poetry. It’s the best way, through a living poet, and I think it even helps John Milton a little bit, for people to recognize that he might have been alive once, a poet fumbling up to the podium to give his poetry reading before these admirers.”

While acknowledging that Irish studies have grown dramatically in the U.S. in the years following the Press’s founding, Johnston denies that the Press has been wholly responsible and credits much of the heightened interest to Seamus Heaney, who has achieved the poet’s equivalent of rock-star status as the Boylston Professor of Rhetoric at Harvard.

“Seamus’s popularity has had a great deal to do with it. But I think then the pleasure people have is in finding that there are other poets,” Johnston said. “He deserves his acclaim, but there are these other poets who are very powerful and were there before; people like John Montague were there before Seamus doing very good things.”

Nonetheless, it was Wake Forest University Press that brought many Irish poets to the American public, and it has a surprising amount of influence for such a small, incongruous organization. Its cramped book-and-paper-filled office on the Wake Forest campus barely holds Johnston, Jones, and an occasional student assistant, yet they steadily publish four to five books of poetry a year, the same as or more than nearly all major publishing houses. And even more important to its survival, the Press is able to sell far more poetry books than other university presses do, as many as major publishers.

They have added a series of French poetry to their list as well, starting with the 1989 publication of Philippe Jaccottet, with translations by Irish poet Derek Mahon, which prompted The Times Literary Supplement to comment that “Wake Forest University Press has expanded to become a major source of European poetry in the United States.”

And much of the credit surely must go to the time and energy that the Press lavishes on each project. “It’s tiny,” Johnston said. “But when you think about how much editorial time is given to poetry at a major publishing house — you know, if you call a publishing house and ask for a poetry editor, often they say: ‘He or she is in on Tuesday,’ and that’s it, or they may have somebody who does a lot of other things, because there’s no way to justify giving the time to poetry.”

Ciaran Carson, who has been associated with the Press for nearly 20 years, finds that the small scale of the Press’s operations makes them very easy to work with. “I think that’s the whole thing about it, that it’s personal, it’s very intimate. If you want a book done in your own way, then it’s done in that way. There’s no hangups, there’s no hassles, there’s no complications. We don’t have rows — we’re friends.”

Nuala Ni Dhomhnaill, who writes exclusively in Irish, sees parallels between the battles she fights for the Irish language and Dillon Johnston’s struggle to bring Irish poetry to America. “In the face of uncongenial circumstances, they do something which doesn’t obey the rules of marketing or economics — good for them. And they put out such classy productions.”

She has nothing but admiration for Johnston’s work. “The man has the panache to write about Irish poetry after Joyce. What about Irish prose after Yeats? That should be his next book. Imagine having the panache to do that!”

The real question, though, is why any of these Irish poets are so popular in the United States. Heaney with his appearances in Vanity Fair aside, many lesser-known Irish poets are still welcomed with open arms around the country, and, as poet Alfred Corn wryly observed in Poetry magazine, “greeted with praise and university employment as soon as they present themselves.”

Last year Wake Forest Press published two books by Nuala Ni Dhomhaill with translations by every star in the Irish poetic universe. Americans had access to her work for the first time, and Ni Dhomhnaill found herself much in demand. At readings in New York in May, Ni Dhomhnaill, Muldoon, Mahon and Carson spoke to packed houses.

Why do any Americans, and not just Irish-Americans, flock to readings to hear Irish poets? It is a question that Dillon Johnston has been asked before. “I think, to give you the short answer, it’s because they are very good” he says.

“I think there is a sense of something going on among the poets. They’re somehow stimulating each other. There is some poetry going on there, which means that there’s some kind of cross-fertilization going.”

Could the phenomenon be as simple as the fact that poetry is relatively mainstream in Ireland, where poets appear on the society pages of newspapers and on TV talk shows, encouraging a wide range of people to pick up a pen?

“I think that’s certainly a good part of it,” Johnston said. “But still, there’s something miraculous about it — it’s such a tiny place.”

And, like any miracle, the reasons for it cannot be pinned down. “It gets into the mystery of why things happen, why poetry happens in little clusters and in different strange places. Why does it happen somewhere that’s a tenth of the population of, say, England?” he said.

“When you think of the amount of activity in Ireland, and when you read them against each other, and Paul [Muldoon] is putting little humorous jabs at Heaney and they’re quoting each other — there’s this real active sense they have of each other.”

But the thing that really sets Irish poetry apart, most critics and poets agree, is the Irish sense of language. There are Irish people who speak and support the Irish language, and those who angrily campaign for its abolishment as a compulsory subject in Irish schools, but everywhere there is the sense that Ireland, like it or not, is still caught in the tug between two languages. And the battle need not be explicit to make a difference in the poetry.

“I’m not even thinking of the language issue so much as that sense that there is this other language, and that it’s there, and it’s having an influence,” Johnston said. “Derek Mahon is not an Irish speaker, but there’s certainly a gap in Mahon’s poetry in the speaker’s use of language. There’s an ironic gap there, it’s like he’s taken Yeats’s language and then taken the stilts down, and left it hanging up there in a sort of suspension — that’s the consciousness of language that I mean.”

From the cryptic Medh McGuckian to the subtle and elusive Eilean Ní Chuilleanáin, Wake Forest University Press has introduced American audiences to a wealth of sophisticated language to which they had no prior access. Johnston sees the English poetic tradition, and, subsequently, much American poetry, as using a more realist, ironic language. It is not a tradition that leaves much room for layers of meaning. “If you’re in charge of the language, you forget. You think you can just say something, and that’s it.”

It is a subject which Johnston has explored at length in his highly esteemed 1985 book, Irish Poetry After Joyce. “That was the idea – just that they didn’t take for granted an audience,” Johnston said. “Their language is not transparent. They’re aware of strategies and doublespeak. It’s a postcolonial situation and they’re aware that you say one thing one way to someone and say something differently to someone else.”

But that’s ultimately the thrill of Irish poetry.

“You start off reading the stuff very closely, and then you realize that you can’t just do that, you have to do that plus know some history, and suddenly you’re thrust into the history and you know that any question like ‘What did you do yesterday?’ brings it back to the Battle of Clontarf or something, by that sort of reverse process of well, I have to explain this and I have to explain this and I have to explain that.”

Johnston paused, as if contemplating the limitless labyrinthian subtleties of Irish poetry. “But I think that what that’s doing is putting the poetry in a human context, so that’s what the final excitement is for me, to return it to that.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the September/October 1994 issue of Irish America. ♦

Leave a Reply