Irish dance takes a leap forward thanks to two Irish Americans and a talented Irish composer.

The lights dropped and the wistful, haunting music began, and a Druidic figure appeared draped in a black cloak. The music swirled and soared, mystical and moving, while the figure’s voice soared with it. The music climbed to its peak, then changed in format to something quicker, more powerful, climbing again to reach a rhythmic beat.

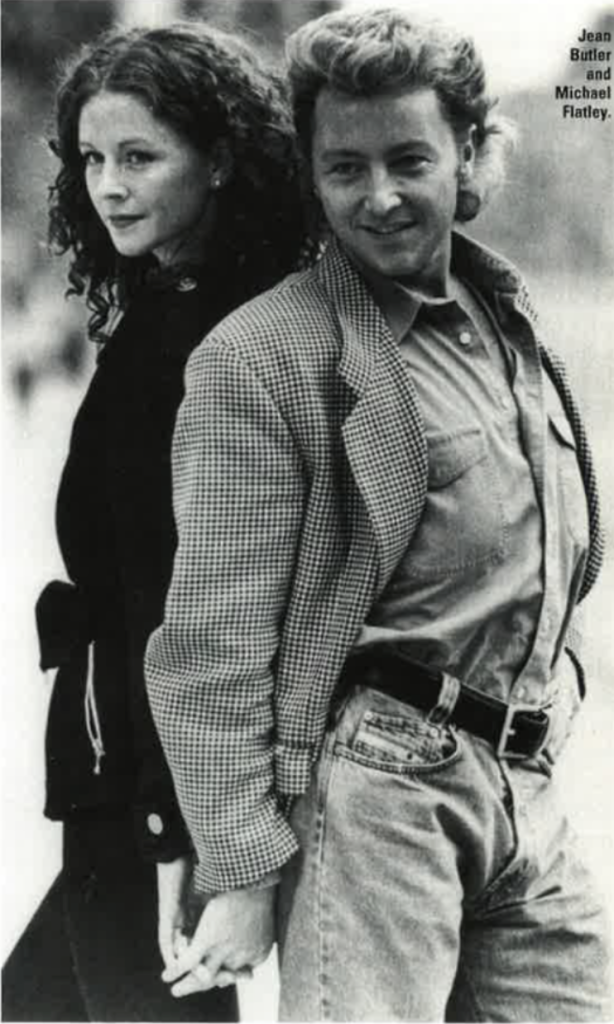

Red-haired, slim, balletic, graceful, Jean Butler emerges from shadow. The music is Irish, the steps and form familiar but… the costume? Where’s the Celtic design? Jean is in black, no design. Her dress is off-the-shoulder. And her skirt is well above her knees. She glides back and forth and around, tilts her head, offers a little smile and, with both hands, caresses her hair.

That is the signal for Michael Flatley to leap onstage, first suspended in mid-air, then tapping, dominant, insistent, primal, King of the Jungle, dancing for his mate. The music becomes a war cry. He is wearing tight black pants, full-sleeved shirt with a blue sheen. He takes the whole stage — and it’s an acre of stage. He is ballet, he is flamenco, he is Eastern European. He is Zorba the Mick.

Jean glides to him. She circles him. She is sensual, seductive: She touches him. I’ll let you chase me until I catch you, her movements say. The pair are joined on stage by a long line of dancers hammering out the primitive mystical rhythm with their tap shoes. On and on it goes, building to a tremendous climax, the beating of the drums the perfect complement for the beating of the dancers’ shoes — it’s a ritualistic triumph. The pure genius of Flatley and Butler sinks in. They exchange little smiles of satisfaction.

The audience is stunned. And then they are on their feet, offering thunderous sustained applause.

In seven minutes two dancers from America changed the world of Irish dance, forever. How did it come about?

In December, 1993, Eurovision song concert producer, Moya Doherty, approached Billy Whelan (of Limerick City) with the idea of composing a dance piece, a piece that would bridge the intermission period in the annual contest, when the judges were out deciding on the winners. (Ireland won the contest, again, for the third consecutive time.)

Chicago native Michael Flatley was commissioned to choreograph the piece, and also dance in it. He, in turn, was asked to select a female partner, and he chose fellow American Jean Butler.

In previous years this intermission was usually filled with bands or filmed pieces. Doherty would change that. She wanted the principals — Flatley and Butler — backed up by a group of hard shoe dancers. And Whelan would have to come up with the music.

In an interview with Niall O’Dowd of Irish America the composer traces the genesis of what came to be known as “Riverdance.” The general images are of land and river, the male and the female, wherein the river calls out to nourish the land. The ‘story’ is introduced by Anuna, the Irish Chamber Choir, led by Michael McGlynn, in song that is, for a better term, New Age: ethereal, spiritual. Jean Butler, in soft shoe, invites land (Flatley) and when the two forces are united (soft to hard) they are joined in celebration by a troupe of dancers and there is a rousing, joyous climax.

“It was an absolutely huge amount of work,” said Michael Flatley, “but it was a lot of fun. For the last two weeks we rehearsed for 14 hours a day. I was in Dublin in January, when the first draft of the music was ready, and I choreographed most of the steps at that time. All of the back line of dancers were Dubliners. Then I went back in April to work with Jean three weeks before the show.”

The piece is intricate, precise and passionate. One misstep could have broken the whole structure yet Moya Doherty insisted on doing it live. In other words, dangerously. (The estimated TV audience was three hundred million!) But Whelan felt, after rehearsals before a live audience, that something powerful was happening. He, himself, was reaching back into centuries of Irish music and dance and was particularly influenced by the music of such groups as Planxty, the Bothy Band, Moving Hearts and by the work of Sean Davey and Mícheal O’Suilleabhain, their desire to ‘grab’ the music, make it relevant to our times. And Whelan wanted to connect that music to the dance. There had been, he says, “sterility”.

The first thing that struck 36-year-old Michael Flatley when he heard the music for Riverdance, he said, was “how extraordinary it was. It’s New Wave — it’s delightful, it’s something you can listen to over and over again.” Best of all though, for Flatley, was the rhythm pattern — it was perfect to dance to. “It’s very highenergy,” he described. “But it’s totally Irish-driven.”

“Riverdance” is an attempt to evoke a more primal state, to connect dance to the actual reason for dancing and that, says composer Whelan, is human sexual expression. “We sometimes forget the wealth of all that expression is there in the tradition and it’s only a question of pulling it out and polishing it.”

And who better to do that than Michael Flatley. Not only did he win the Irish Dancing World Cup at the age of 17 in 1975, he was also three-time All-Ireland flute champion (silver and wood). He is a World Champion tap dancer, too, with a record of a mind-boggling 28 taps per second.

In his native Chicago he was a Golden Gloves boxing champion, a member of Mensa, a qualified croupier and, in his spare time, of course, a world-class chess player. With Mick Moloney he toured the Green Fields of America and often danced with the Chieftains.

His grandmother was a Leinster dance champion, as was his mother, who hails from County Carlow. His father came from County Sligo. “That’s where I got the music,” Flatley joked.

Flatley’s interest in Irish dance was kindled when, as a child, he was taken to a Féis (Irish dance competition). “I had seen ballets already, but I thought there was something in the way that Irish men danced that was very masculine,” he remembered. “I really liked it.” He began to practice, and soon became an expert. “I had an affinity for it, and I suppose I became proficient very quickly. It’s easy then to do something when you are good at it and you enjoy it,” he said.

In Ireland, though, there is — or was — a tendency to dismiss Irish Americans who became embued in Irish music or dance — a feeling that the native Irish were the only ones who could carry on the centuries old traditions. Flatley admitted reluctantly that he sometimes got that feeling when he was competing in Ireland. Yet after seeing Riverdance no-one can doubt that the future of Irish dancing was born in America.

Flatley is but one in a long line of Americans who have flourished in the world of Irish dance. In 1969 Donny Goldin of New York walked away with second place in the World Cup in Irish Dancing. His teachers were Cyril McNiff and Jimmy Irwin, and when he started his own dance school years later one of his students was Jean Butler. He’s been teaching now for twenty-two years and sees changes coming. He doesn’t think the Flatley-Butler Riverdance will change Irish dancing significantly but he does predict more use of the hands by Irish and American dancers — especially since they’re exploring other forms.

Mark Howard, who runs one of the largest Irish dancing schools in the United States, with four locations in the Chicago and Milwaukee areas, and whose Trinity Academy of Irish Dance holds seven World Championships titles is in the forefront of this expansion into other areas. He is currently working on “Rhythm in Shoes,” with Gregory Hynes and Savion Gover, a compilation of Irish dancing and tap dancing which will travel the United States.

But what about the ‘tradition?’ Won’t the purity of Irish dance be tainted by Flatley’s flamenco and Butler’s ballet?

“I dance with a progressive style,” said Flatley. “Maybe some purists don’t like that, but the people certainly showed that they did.”

Mick Moloney doesn’t think the tradition will suffer, either: the reverse might be true. He feels choreographers in modern dance might now reach into the Irish tradition for ideas — once they see “Riverdance.” The Flatley style is ‘show’ dancing and that will surely attract more and more young Irish dancers even as the ‘tradition’ is more and more refined.

Flatley and Whelan allow music and dance to breathe freely and this ‘breathing’ promises to develop into a storm under the genius of these artists. Flatley knew he and Butler would literally kick up a storm on the night of the performance in April, because the five dress rehearsals they held in front of the press and full audiences brought very enthusiastic receptions.

“But we didn’t expect a reaction this strong,” Flatley said happily.

The morning after the live performance, the dancers were invited to attend an audience with President Mary Robinson. The Riverdance CD has just broken the Irish record — it has been number one in the charts for 15 weeks, ever since it was first aired.

And although RTE, Ireland’s national broadcast authority, was deluged with calls from all over Europe requesting copies of Riverdance on video, a contractual problem developed and no visual recordings were available.

But Riverdance producer, Moya Doherty, had another brainwave. The Riverdance video would be sold, but all the proceeds would go to help the needy in Rwanda, and that would solve the contractual problems. The participants immediately agreed. Michael Flatley had been in Europe traveling, and everywhere he went, he said, he was bombarded with CNN reports of the crisis in Rwanda. “I couldn’t take the pictures from Rwanda anymore,” he said. He knows he could have made a tidy fortune from the video sales, yet his only concern now is to “get the money over there as soon as possible.”

So this extraordinary episode in Irish culture would seem to have an extraordinary ending, except, happily it’s not over yet, not by a long shot. Plans are underway to turn Riverdance into a full-length musical, with, of course, Bill Whelan composing the music. While the original Riverdance will be performed in the Royal Albert Hall in London on November 18, and then at the Royal Command Performance on November 28, according to Flatley (who has been offered work in London’s West End), the musical is scheduled to open at Dublin’s Point Depot next January.

“The people involved, especially the producer and the director, are very serious about this,” Flatley explained. “Paul McGuinness (manager of U2) is involved in the promotion, and some other Irish heavyweights are involved. The main goal is Broadway sometime next year.”

The world champion dancer and his wife of nine years, Beata, expect to leave their Beverly Hills home pretty soon to spend eight or ten months in Ireland, so Flatley can submerge himself in the world of dance once again, to mesmerize his audiences all over again.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the September/October 1994 issue of Irish America. ♦

Leave a Reply