Deáglan de Bréadún reports on former Senator George Mitchell’s efforts to resolve the conflict in the North of Ireland.

Dear shadows, now you know it all,

All the folly of a fight

With a common wrong or right.

The innocent and the beautiful

Have no enemy but time.

Those words of the Irish poet W.B. Yeats referred to an earlier chapter in our national story: an earlier conflict, with earlier casualties.

But they could be applied today. The “shadows,” of course, are of the dead. One wonders if the dead are watching the latest efforts to resolve the conflict in the North of Ireland.

There have been three thousand deaths because of the Troubles over the past 25 years: men, women, children; innocent civilians shot walking down a street; bomb victims; Irish Republican Army (IRA) members shot by the British Army; British Army members shot by the IRA; politicians on all sides; little girls killed by plastic bullets; policemen blown up when they started their cars; fathers, mothers, sisters, brothers, sons and daughters.

For some weeks now I have been covering the multi-party peace talks at Stormont, just outside Belfast. It’s an eerie place, especially in the evenings. There are times when a breeze is blowing that one fancies it is the voices of the dead, whispering and praying for a settlement: too late for them but not too late, we hope, for the rest of us.

The chairman of the talks is George Mitchell, formerly a U.S. senator and federal judge. The task he faces is seen by many as the equivalent of trying to square a circle. He will fail, they say, as so many have before him. The problem in the North of Ireland is insoluble, they say.

Certainly the job he has undertaken is not an easy one. Soon after he took over, the IRA killed a policeman in the Irish Republic and exploded a bomb in Manchester, England. Hopes of a ceasefire suffered a major setback. For Mitchell, it was one more problem to surmount, as the absence of Sinn Féin from the political talks makes it very hard for them to succeed.

The conflict, of course goes back centuries. There is an old joke about the pilot flying into Northern Ireland’s biggest city who advises his passengers: “We are now arriving in Belfast; please adjust your watches to 1690.”

At about the same time that the Mayflower was sailing to America, English and Scots settlers were arriving in the North of Ireland to set up farms and build new towns. The indigenous population, thrown off their lands, revolted and the whole issue got caught up in a war over the English throne. The native Irish suffered some historic defeats: first when they failed to capture the city of Derry (or Londonderry as the settlers called it) and then at the Battle of the Boyne.

Despite the way it is portrayed in the international media, the conflict in the six counties called Northern Ireland is not a religious war but a struggle between two nationalities. There are about one million unionists, virtually all of them Protestant, who wish to remain in the United Kingdom with Great Britain. There are some half a million nationalists, most of them Roman Catholics, whose desire is to be part of an independent united Ireland.

The partition of Ireland into two separate states was a solution nobody had originally sought. The unionists would have preferred to see the whole island remaining under the British crown but came to the conclusion that the six northern counties were the most they could hold; the nationalists wanted the whole island to be free.

A regional parliament was set up in Northern Ireland. It was based at Stormont, close to the location of the present talks. For 50 years, the unionists operated a system of government that has often been compared to South Africa under white domination or the pre-civil rights days in the deep south of the U.S. Nationalists had no real role in government and were the victims of discrimination in housing, voting rights and employment.

Inspired by Martin Luther King and the African-American civil rights struggle, the nationalists launched a campaign of marches and civil disobedience in the late 1960s under the anthem “We Shall Overcome.” They were met by a largely repressive response, culminating in the shooting dead of 13 unarmed civilians by British paratroopers on “Bloody Sunday” in Derry in 1972.

The IRA, whose guns had gone silent, reappeared on the scene, first in the role of defenders of the nationalist community and then as guerrillas waging an aggressive campaign to end British rule.

The British government scrapped the Northern Ireland parliament in 1972. As a result of an agreement signed at Sunningdale, England, a power-sharing administration was established in 1974 with representatives from the nationalist and unionist communities. This collapsed when Protestant workers, led by extreme unionists, went on strike and brought Northern Ireland to a standstill.

It was 1985 before another major attempt, the Anglo-Irish Agreement, which for the first time gave the Irish Republic a say in Northern Ireland affairs, was signed. The current peace phase began when then Irish prime minister Albert Reynolds began a series of negotiations with Sinn Féin aimed at bringing about a new IRA ceasefire.

With major help from the Clinton administration and John Hume, leader of the SDLP, the North’s largest nationalist party, he succeeded in August 1994. What followed was a ceasefire of 17 months duration, which ended after the British government refused to bring Sinn Féin into talks. Now Mitchell has been appointed to try to facilitate such an historic event.

The imposing — some would say arrogant — parliament building at Stormont remains empty. Perhaps as he drives past each evening on his way from the talks Senator Mitchell wonders if it will ever be occupied again.

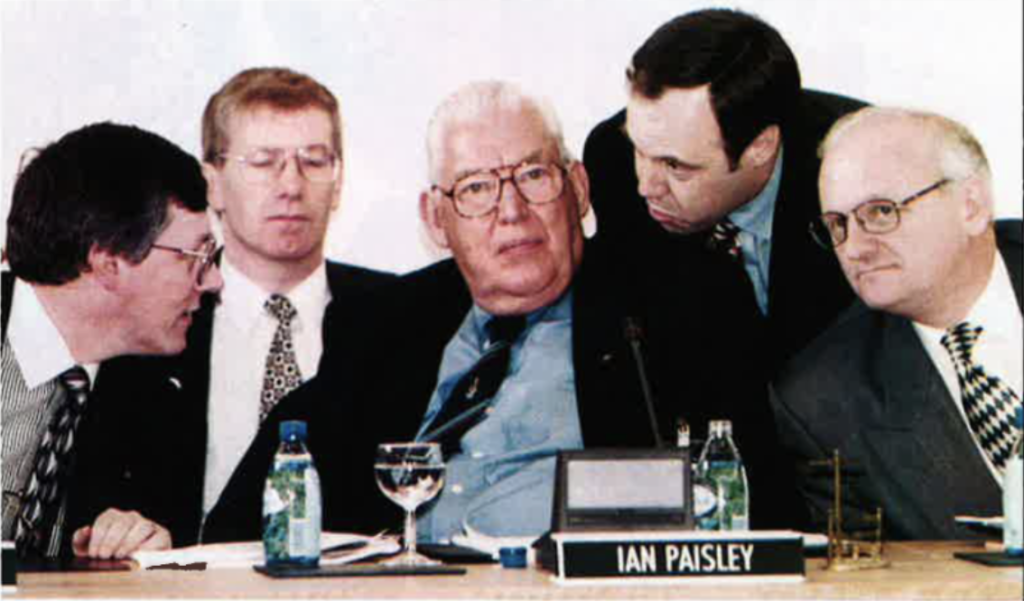

Senator Mitchell became the talks chairman at the request of the Irish and British governments. But some unionists objected because they saw his appointment as part of a nationalist agenda. The Reverend Ian Paisley, leader of the Democratic Unionist Party, and Robert McCartney, leader of the smaller United Kingdom Unionists, staged an angry walkout.

But in a highly significant development, the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), the biggest political party in the unionist community, decided to support Mitchell provided its members would have an opportunity to redraft the rules and procedures so that they could feel the new chairman was answerable to them and the other parties rather than the two governments.

On the night he finally took the chair, Mitchell was walked into the room by members of the loyalist paramilitary parties, despite jeers from Ian Paisley and other extreme unionists. The loyalists very much want his steady hand on the tiller at the talks. Ironically, Mitchell is seen by the two extremes, the IRA and its counterparts, the UVF and UDA, as the only person who can ensure they get fair treatment on the issue of handing over weapons.

Although Paisley and McCartney had walked out they soon walked back in again, mainly to see what their UUP rivals were up to. The UUP claimed to have achieved significant procedural changes in the talks, but the others sneered and belittled these gains.

As a former majority leader in the U.S. Senate, Mitchell has much experience of the tactics of obstruction. But he has been surprised at the objections made against him because of his alleged religious background and leanings.

“This is a new experience for me,” he told a reporter from The New York Times. “In thirty years in American politics, no one ever asked what my religion is or where my parents were from.”

Turn your watch back to 1690. Bizarre as it may seem to many U.S. readers today, one’s religious affiliation can be — and often is — a factor in Northern Ireland politics (remember John F. Kennedy’s problems when he was running for president). Although the main objection to Mitchell from hardline unionists was that he was a “frontman” for Bill Clinton and the Kennedys, who are regarded as pro-nationalist, there were also rumblings about his Catholicism and his Irish ancestry.

The Independent, an English daily newspaper, conducted an investigation of Mitchell’s background and reported that, although his paternal grandfather was Irish born, his mother was Lebanese and he himself was brought up in the Lebanese community of Waterville, Maine.

“He likes to eat Middle Eastern staples such as stuffed vine leaves, lentils, and goat’s yogurt,” the paper reported. That’s a long way from corned beef and cabbage!

And his Catholicism is different from the Roman Catholic variety; his family were Lebanese Maronites and it appears that Senator Mitchell is not a particularly religious man.

However, Senator Mitchell was associated with the Congressional Friends of Ireland group and was among those who signed a letter circulated by Senator Kennedy in January 1994 seeking support for a U.S. visa for Gerry Adams, president of the IRA’s political wing, Sinn Féin (Irish for “Ourselves Alone”) who had previously been banned from the U.S. The granting of the visa in the face of strong British objections, and the public relations success of the Adams visit are said to have helped in securing an IRA ceasefire in late August that year.

In 1995 George Mitchell was appointed as President Clinton’s special advisor on Irish economic initiatives with a brief to combat the unemployment and economic deprivation which provide such fertile breeding-grounds for violence. I first saw him during Clinton’s Irish visit, when the President stopped by a special project set up to bring jobs to East Belfast, one of the heartlands of hard-line unionism. I was struck by how quiet-spoken he was (compared to Clinton!), the detailed knowledge he had already acquired of the Northern Ireland situation, and his obvious affection for the place and the people.

By the time of President Clinton’s Irish visit, the IRA ceasefire had been in operation for over a year. But there were ominous hints and rumors that all was not well. Adams and others from the movement’s political wing charged that the British government was dragging its heels and was not really interested in a negotiated settlement.

It was certainly true that the British had put themselves on a political hook by demanding that the IRA hand over some of its weapons and explosives before Sinn Féin could be admitted to peace talks. This was denounced by Irish republicans as the equivalent of a demand for surrender. The situation had reached a dangerous stalemate.

Mitchell was asked by the Irish and British governments to head up a three-member body to investigate the weapons dispute and come up with a solution. Along with a former chief of the Canadian defense forces, General John de Chastelain, and a former Finnish prime minister, Harri Holkeri, Mitchell invited all the parties to the conflict to meet him in private to discuss the weapons issue.

The report was ready in less than two months. Its clarity and lucidity came as a pleasant surprise to a public more used to fudge and obfuscation from its politicians. His solution was simple: The British and the unionists want weapons handed over in advance of talks; the IRA wants to keep them until the talks have reached a settlement; so why not consider a step-by-step handover while the talks are taking place?

A simple and obvious solution, but it needed an outsider with the prestige of the U.S. government at his back to get the parties to consider it seriously.

Unfortunately, even Mitchell’s injection of good sense and clear thinking could not save the situation at that stage. Reportedly embittered by what it saw as Britain’s delaying tactics, the IRA ended its ceasefire by exploding a massive bomb in London which killed two people and caused an enormous amount of damage.

There have been other IRA actions since then and prospects for peace look distinctly shaky. The Irish and British governments finally set June 10 as the starting date for the peace talks but decreed that Sinn Féin could not be admitted until there was another IRA ceasefire. There are reports at time of writing that such a ceasefire may be announced soon.

Although an Irish government official said peace talks without Sinn Féin were “not worth a penny candle,” the discussions are going ahead under Mitchell’s chairmanship and a lot of people are keeping their fingers crossed, hoping for another IRA ceasefire so that Sinn Féin can also take part.

It is too early to make a definitive judgment about Mitchell’s role and effectiveness. But even those who criticized his appointment have praised him as a man of courtesy and distinction. His patience and diplomatic skills have already been in evidence in the early procedural wrangles but he must know better than anyone that difficult times lie ahead. If he succeeds in steering the talks towards a lasting settlement, he will deserve the Nobel Peace Prize ten times over (he will also have boosted the reputation of his President). If he fails and retires exhausted and disillusioned by the squabbling and the bigotry, he will nevertheless have secured a place in Irish hearts as a good man who tried his best to bring peace.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the July/August 1996 issue of Irish America. ⬥

Leave a Reply