An Irish dancing teacher brings her American students back home.

Christina Ryan is from Miltown Malbay a tiny, rural, coastal town in County Clare, and though she came to America five years ago she never really left it behind. In her new hometown of Richboro, in Bucks County, she slowly developed her Irish dancing school, and over the years a handful of dancers evolved into more than 100 students from three neighboring communities.

In regional competitions from New York to Washington, the young dancers made themselves known. This year, in fact, several dancers from the Ryan School qualified for the World Championships. Still, as her school flourished, Christina’s heart kept pulling her back to Miltown Malbay. From time to time, she would disappear, and someone would explain, “She’ll be back in two weeks.” Then, this Spring, after a solid year of planning, Christina’s dreams came together. She brought 65 of her dancers and their families to Ireland, ostensibly to dance in the St. Patrick’s Day Parade in Dublin, but really she wanted to show them her home town.

There, in County Clare, the American children got a true sense of what she had left behind. They learned steps with native Irish dancers, stayed in their homes, attended their schools, caught on to a few phrases in Gaelic, toured castles, caves and the Cliffs of Mohar, sipped tea, ate scones, listened to fine musicians and fun story tellers, and had endless hours of great craic.

Lizzy Curtin, a local character who treated the children with stories of pirates whose ship was dashed along the rocky coast, said in her simple, poetic style that though she has never left County Clare she feels like she’s been all around the world. “You see,” she explained, “County Clare brings people to me.”

While people settled in Miltown Malbay in the earliest Christian times, Lizzy explained that the presence of corn mills in the 19th century accounts for the “Milltown” part of the name, while “Malbay” comes from an Irish word meaning “treacherous coast.” And, in the off-season, the wind whips off the ocean, with a chill that can cut to the bone.

In the center of town there is a small factory, where heavy knit sweaters are woven by about twenty residents. During the day, the factory opened its doors, and most every American tried on a heavy woolen cardigan or pullover, and, shivering, said, “This will be fine. Just cut off the price tag for me, and I’ll wear it outside.”

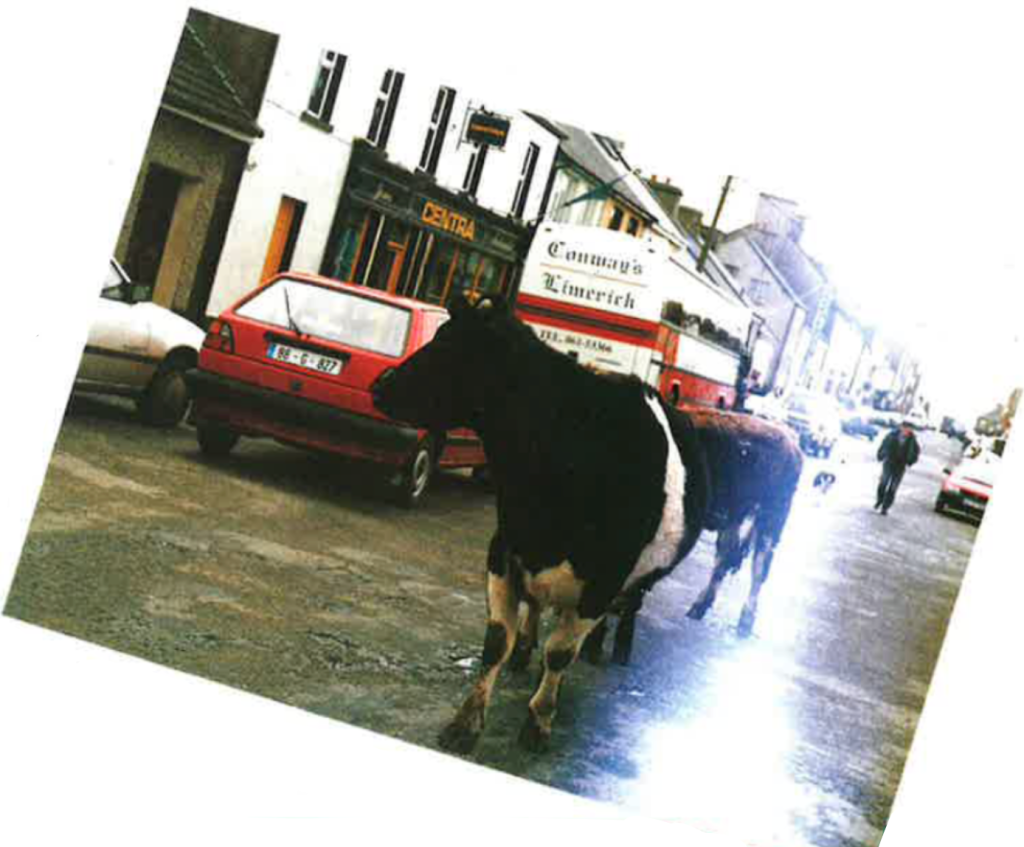

Paddy Maroney, one of the farmers who would sometimes walk his cows through the center of town, said that the cold wind whipping off the ocean doesn’t really bother him when he’s working the fields. “I just think about how good I’m going to feel when I’m done and resting in front of the fireplace with a pint.”

And Tom Munnelly, who for the past twenty years has been chronicling traditional Irish folk tales for Trinity College, said, with his tongue firmly planted in his cheek, that he could not confirm that music was invented because the dancers needed something to perform to. But he said he had been told that the harp, Ireland’s traditional instrument, was first discovered when a strong wind blew through some whale bones that had washed along the shore in Miltown Malbay.

On one memorable evening Christina took her dancers to a nearby town to share their steps with some of the students she used to teach with her friends Anne O’Connel and Lily Slevin. As a fiddler and a tin whistle player kept the rhythm moving faster than a heartbeat, dancers from both sides of the Atlantic demonstrated the fine form of their ritualized craft. It’s said that the beauty of Irish Step Dancing is that the music goes directly from the ears to the feet. Up on their toes, arms straight at their sides, their heels clicking, their grace was amazing. In felt costumes with embroidered Celtic designs, the dancers defied gravity. One of the night’s stand-outs was a tall, handsome young man named John Saunders, who has qualified for the World Competitions. Each time he’d kick, it was as if he was going to flip over. Then he’d kick even higher still, clicking his heels together before landing. And any of the American girls who had a chance to dance with him were still wearing smiles a week later as they crossed the Atlantic.

Keri Surgoft, a 12-year old from Langhorne, who has been taking Irish Step Dancing lessons for five years, said that dancing with the students from Ireland “inspired me to work toward trying to be as good as them.”

Katie Sweeney, a 12-year old from Yardley, who has also been Irish Step Dancing for five years, added, “I don’t know if they’re so good because of their heritage, or if they practice more, or because they grew up with it. But being with them made me realize that dancing is part of who I am, and to want it more.”

Just what is it that draws these young Americans to Irish Step Dancing?

For some of the American students, Irish Step Dancing has definitely been handed down through the generations. Erin Buchanan, for example, a 13-year old from Hamilton Township, New Jersey, who has been taking Irish Step Dancing lessons for nearly half her life, is following in her mother’s footsteps. And her mother’s father, himself, was a Step Dancing teacher.

Cathy Lee, a 13-year old from Penndell, who has been Irish Step Dancing for four years, summed it up by saying, “It’s great fun — the performing, the competitions, the music. I’ve made a lot of friends, and gotten to travel to so many fun places. And now, to be in Ireland — this has all been such a dream.”

After an unforgettable week, the Ryan School was to leave Miltown Malbay, off to Dublin to be the first group of American youngsters to participate in that city’s St. Patrick’s Day Parade. While there is no parade quite like it, as several of the dancers said, “Dublin is real nice. But it just isn’t Miltown Malbay.”

One Miltown Malbay native halfjokingly explained that the reason the Irish are so kind to Americans is because there is a very good chance that they might be talking to one of their relatives. But the Irish spirit, the warmth and genuine interest in others, goes much deeper than that.

Tara Sweeney, a nine-year old from Yardley, who has been a student of Christina’s for four years, said that her favorite part of Ireland was the family she stayed with. That family — Mary, Harry, Aoife, Ciaran and Deirdre Hughes — were the consummate hosts, introducing new friends, informing of interesting parts in and around the town, and sharing their essence. And, since Harry runs the Willie Clancy Summer School, a week-long festival in July which features traditional Irish music, song and dance, he was able to acquaint the Americans to a cadre of topflight musicians and story tellers, who could entertain well into the night. Already Tara and her sisters have written back and forth to the Hughes children, exchanging photographs and dreams, and planning how they can get together again.

The last night on the West Coast was full of hugs, tears and exchanging of addresses. Friendships had been formed that run very deep. There was even the hint of a first romance, as a twelve-year old Ryan Step Dancer, heart-sick from leaving this tiny coastal town, was greeted every night at the hotel where her family was staying in Dublin by a young lad from Miltown Malbay who left longing telephone messages.

But the royal send-off came as the Americans began boarding the buses. Down the middle of the five-block long main street in Miltown Malbay, Peter Cleary, a local farmer, chased his two cows through the mist and waved good-bye. And the Americans and their new-found friends all broke out laughing, snapping final photographs, wiping the trace of tears, and giving each other one last hug.

It was just one of those perfect moments.

A send-off to be remembered.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the May/June 1994 issue of Irish America. ♦

Leave a Reply