They built the roads and the canals, and died in their thousands from yellow fever. They competed with slaves to load cotton on the ships bound for Liverpool. Ships that would return crowded with famine Irish. They owned coffee houses. They took part in politics and some lucky ones became millionaires and sugar plantation owners.

Harry Dunleavy writes on the extraordinary history of the Irish in one of America’s most colorful cities.

In 1682, Robert de la Salle, a wealthy young Frenchman from Rouen, led an expedition of 56 men down the Mississippi (Father of Rivers) to the Gulf of Mexico, which he reached on April 9 of that year. He claimed all the territory drained by that river for France and named it Louisiana in honor of his king, Louis XIV. A city was needed to control the commerce of the river; and in 1718, another Frenchman named Bienville set about building New Orleans on a crescent formed by the mighty river 100 miles north of where it empties into the Gulf of Mexico, and just south of the shallow, vast and beautiful lake called Pontchartrain. In 1723, the city was declared the capital of the Louisiana Territory, a huge tract of land extending all the way to the Canadian border.

The site that Bienville selected for New Orleans created problems almost from the beginning. A year after the little town was laid out the Mississippi overflowed and a levee had to be constructed to keep out the water. In 1731, Irishman Charles McCarthy arrived with a detachment of French engineers and set about devising methods to control the floods. McCarthy received large tracts of land around New Orleans as a grant from the French government, land which remained in the family hands for several generations.

The city remained French until 1762 when Louis XV bequeathed it to his cousin, Charles III of Spain. The French citizens of Louisiana were not privy to the transfer until 1764, and no Spanish official was sent to take charge until 1766, when Don de Ulloa arrived. After a minor revolution by French colonists in 1768, Ulloa was forced to flee to Havana, Cuba.

The Spanish king, furious at the rebellion, appointed Don Alexandre O’Reilly governor and captain general of the province of Louisiana. Born at Baltrasna, County Meath in 1735, O’Reilly emigrated to Spain with his parents as a boy and became a cadet in the Hibernia Regiment. Arriving at the mouth of the Mississippi on July 20, 1769, with 2,056 soldiers, O’Reilly immediately set about bringing the area under Spanish control. His methods, including ordering the five leaders of the revolution to be shot by Spanish soldiers, earned him the title “Bloody O’Reilly.”

O’Reilly’s era did have some merit, however. He established land titles and a system of homesteading under which a farmer was allowed to have a parcel of land six to eight arpents (191.835 feet) long fronting a river or bayou, and 40 arpents in depth, provided he occupied the land, cleared its front, and enclosed it within three years. Roads and levees were built during his administration and Indian slavery was abolished. He divided medicine into three disciplines: medicine proper, surgery, and pharmacy. He abolished the old French Superior Council and substituted it with a governing body, but allowed former French officials to retain their positions and stay in the territory. He also made Catholicism more forceful and conservative, and closed down houses of ill-repute.

Oliver Pollock, a native of Derry, was an established merchant in New Orleans when O’Reilly arrived as governor. Having enough food in his warehouses to feed all the Spanish troops, Pollock and his New Orleans-born wife, Margaret O’Brien, became close personal associates of O’Reilly. This friendship was reciprocated with profitable trading privileges for Pollock. He became purchasing agent in New Orleans for the American rebels during the revolutionary war against Britain with permission from the Spanish governor, Galvez. In late 1770, O’Reilly said good-bye to Louisiana forever, handing over the reins of power to Don Luis de Unzaga.

On June 1, 1800, Louisiana was retroceded to France by Spain and three years later, Napoleon sold it to the United States for $15 million. This acquisition doubled the size of the country and almost brought about the impeachment of Thomas Jefferson. In 1812, the Orleans section of Louisiana Territory became the modern state of Louisiana. The remainder was eventually divided up into 13 other states.

The Battle of New Orleans

When the Battle of New Orleans came along in 1815, a sizable Irish population existed in that city. They joined the American forces which consisted of French, Germans, Blacks, and Choctaw Indians, and fought under Andrew Jackson, who was born shortly after his parents arrived in the United States from Carrickfergus, County Antrim.

At Chalmette, a few miles down river from New Orleans, on January 8, 1815, the British led by Edward Packenham were mowed down during their second charge. Packenham was killed and the leadership of the British then passed to Major General John Keane. Born at Belmont, County Waterford, on February 6, 1781, Keane had seen previous action in Europe. He attempted to rally his men, but they were decimated and the survivors ran away. Keane himself was badly injured but survived. The battle was won decisively by the Americans, and the courage of the Irish under fire, especially a Dr. William Flood, received high praise from Jackson, who would go on to become the seventh president of the United States.

Early Immigrants

Irish immigration to New Orleans before 1820 was distinctly different from that of later years. The early Irish immigrants were, with a few exceptions, people with either education, means, or trade and business skills. A sizable proportion of these early immigrants were Northern Presbyterians, several of whom appear to have had nationalist tendencies. These early Irish, of both persuasions, appear to have been proportionately represented in printing, education, medicine, law, and small and big business.

The early business institution in which the Irish appeared most prominently was the coffee houses, which in those days were a combination of boarding house, restaurant, bar, paper-stand, wholesale house for provisioning ships, and a social and political gathering place. Early coffee houses such as “The Louisiana,” “Orleans,” “Kentucky,” and “Tennessee” had Irish proprietors. Some of the early Irish were also prominent in big business, and the names of Daniel Clark, Oliver Pollock, James Workman, and Kenneth Laverty came to the fore. Clark, who inherited money from his uncle, was one of the wealthiest men in New Orleans around 1800. He owned the Houmas Plantation, the best known in Louisiana, many other properties and river boats, and was deeply involved in the import and export business between Philadelphia and New Orleans. Clark was the U.S. Consul in New Orleans at the time of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. In 1805, he became director of the newly-formed Louisiana Bank whose first teller was named James Fitzgerald.

The first Irish school in New Orleans was opened by Nugent and McKinsey in 1811. In 1816 an English language school was opened by John O’Connor. Two more Irish-owned schools opened in 1822, followed shortly thereafter by an Irish music school and an Irish dancing school. Even an Irish-owned finishing school for acquiring social graces came into existence around this time.

Even though an Irishman, Augustine McCarthy, was elected mayor in 1815, the Irish were not a sought after political entity until 1828, during the Jackson versus Adams presidential election. In 1830, their overwhelming support for mayoral candidate Denis Prieur unquestionably tipped the scales in his direction. By that time, Irish immigration to New Orleans had gone from a trickle to a torrent.

The Hibernian Society

James Workman was one of the most outstanding individuals of the early New Orleans Irish. He dominated the Hibernian Society for well over 20 years. As director of its benevolent chapter, he was the leading crusader for the erection of an asylum for destitute boys. He was a tireless worker for the Saint Patrick’s Day festivities and an Irish nationalist at heart. He raised $1,518.50 for Daniel O’Connell’s repeal movement, the largest sum raised in any U.S. city at that time. An attorney and linguist, Workman’s skills won him an appointment to the judgeship of the superior court of Orleans. He authored acts creating academies in every parish and a university in the city of which he was the first regent. Relentless efforts were also made on his part to build a public library system, and he became a charter trustee of a library for the youth called the “Youth’s Free Grecian Library.” Additionally, he served as a commissioner of the New Orleans law library which was incorporated in 1828. He owned his own law firm and also served as director of several local banks. For a time, he was president of the Orleans Navigation Company. He died in 1832 when his yacht overturned and he drowned.

Early Entrepreneurs

While the majority of the Irish who became successful in New Orleans prior to 1820, such as Clark, Pollock, and Workman, came with either skills, money, and/or education, there were exceptions. Maunsel White, a native of Tipperary and a veteran of the Battle of New Orleans, arrived penniless in that city at the age of 17. After a brief period as a clerk, he became a commodity dealer working on commissions, and went on to make millions in real estate dealings. He built himself an impressive mansion on Julia Street in the American section of town and married into an old established French family, the Larondes. He served for a time as a commissioned officer in the Republican Greens, an Irish American militia unit. White was a social climber who ingratiated himself with the rich and famous including the future president of the United States, Andrew Jackson. In later years, he retired to his plantation home, Deer Range, a few miles down river.

Like White, John Burnside made millions on real estate and bought himself a palatial home on Washington Avenue, also in the American section. Later on, he bought the historical sugar plantation, and estate, with 12,000 acres, from Daniel Clark. He purchased an additional 8,000 acres, built four mills to process the cane, and eventually became one of the prime sugar producers in America. Today, Houmas House, so called because it was built on land originally owned by the Houmas Indians, is open to the public.

The Irish Channel

New Orleans’ main thoroughfare is Canal Street, the widest street in America. It runs mainly in a north-south direction from the river towards the lake. When Louisiana was purchased from France by the United States in 1803, all of New Orleans existed east of Canal Street. That area is still known as the French Quarter or Vieux Carre. After the Louisiana purchase, an American or English-speaking sector developed west of Canal Street.

In later years part of this section, which was exclusively Irish, took up about 100 city blocks and was known as the Irish Channel. In its heyday, it was also the center of Irish social life. A third district, known as the immigrant district, developed east of the French Quarter in the early 1800’s; and a section of this area along the Mississippi became predominantly Irish during the Famine immigration period.

Irish immigration to New Orleans increased exponentially between 1820 and 1845. These new immigrants would become the victims of political exploitation, yellow fever, cholera and violence. Before the arrival of the Irish in large numbers, New Orleans was politically divided between the English-speaking Americans and the French. The majority of the French and the early established Irish belonged to the National Republican Party, the party of the rich. In 1834, the National Republican Party became known as the Whig Party. The English-speaking Americans in the west side of town were originally Democrats, but that would change in due course. By 1828, the Irish held the balance of power. The two major political parties, Democrats and National Republicans, went after their votes through their respective newspapers in the presidential election of that year. The Democratic newspaper continuously reminded the Irish that their candidate, Andrew Jackson, was the son of Irish immigrants who had whipped the British at the Battle of New Orleans. They even went as far as to say that any Irishman who voted for Adams, the National Republican candidate, would have to be an Orangeman or a Shoneen. The National Republican paper made similar counter charges, but Jackson was successful in getting the overwhelming majority of Irish votes.

In the 1830s, New Orleans was the major port for exporting cotton from the United States. Ships were sailing regularly with bales of cotton for Liverpool, and returning with immigrants, a majority of whom were Irish. These new immigrants would build the canals, roads, railroads, and levees around their adopted city. Irish shops, bars, dance halls, and hotels began to spring up. The first of several churches, Saint Patrick’s, was opened in 1833.

Yellow Fever

New Orleans was still a small city in 1830 with a population of only 53,202. The city then occupied only the southeastern tip of the crescent formed by the Mississippi River. The Carondelet Canal, built during the Spanish era, extended north linking the

French Quarter with Lake Pontchartrain and the Gulf of Mexico via The Rigolets Pass. In 1830, the Pontchartrain railroad, second oldest in the United States, was built by Irish immigrants. Its train, “The Smoky Mary,” gave the French Quarter a second mode of transport to the lake. The American section of the city had no such connection. A second canal, the new Basin Canal, was built by Irish immigrants. The arduous task of digging the canal through alligator and snake-infested swamps began in 1832. In that same year, a cholera epidemic hit the city and 6,000 people died in 20 days, many of whom were Irish. When the canal opened for traffic in 1838, there were 8,000 Irish laborers who would never see their homes again, having succumbed to cholera and yellow fever. It was the worst single disaster to befall the Irish in their entire history in New Orleans.

Ironically, the New Orleans canal and banking company which owned and built the canal was founded by the aforementioned Maunsel White, and another Irish-born gentleman, Charles Byrne, was a major shareholder. Financially, the canal was a success as it opened up trade with communities north of Lake Pontchartrain and the cities of Biloxi, Mobile, and Pensacola on the Gulf of Mexico. As the city spread north, finally reaching the lake, its usefulness began to decline. The last remaining stretch was filled in little more than four years ago. A fund was recently established to erect a monument to the thousands of Irish who lost their lives building it.

The new Irish of the 1830s also found extensive employment in the cotton industry loading the bales onto ships and packing them in the holds, often competing for work with black slaves who were hired out by their masters. Many of the new Irish also found work on river boats and delivering goods with horses and drays.

Political Clout

Between 1816 and 1846, the great majority of Louisiana state governors were of French extraction and belonged to the National Republican and/or Whig party. However, in 1834, neither of the two major candidates for state governor were French. The Whigs nominated Edward White, who was of Northern Irish extraction, while the Democrats put forward John Dawson. White chose a wealthy Northern Ireland plantation owner, Judge Alexander Porter, to sway the Irish vote away from the clutches of the Democrats. The aristocratic Porter traveled frequently from his plantation, “Oak Lawn,” at a place called Irish Bend on the Bayou Teche, in the heart of French-speaking southwestern Louisiana, to the poor Irish neighborhoods of New Orleans. He made his presence felt regularly at Irish dances, parties, and social gatherings, where he sang Irish songs, danced Irish jigs, and gave speeches. Porter’s task was a difficult one, and the Democratic press vilified his behavior. They continuously criticized him for being an aristocrat who had no interest in the working-class Irish except their vote. However, Porter had one important qualification: his father was hanged by the British for his part in the Rebellion of 1798. His sincerity, therefore, could not be questioned. On the day of the election, Dawson allegedly hired some Irishmen to harass other Irish voters and keep them away from the polls. White won the election, and subsequently appointed several affluent Irish to high places in state government.

Millionaires

The Irish immigrants of the 1830s and early ’40s did not all settle down to a life of menial labor. The names of three new Irish

millionaires, John Hagan, Thomas Barret, and Charles Byrne, came to the fore. Barret was a director of the corporation which regulated boat traffic on the Carondelet Canal, in addition to being a bank president. In the late 1830s, he was appointed collector of customs of New Orleans, a powerful political position. Barret had several other business interests and Hagan was a partner in most of them.

However, the man who left the most lasting impression on New Orleans during this period was the architect James Gallier. Born at Ravensdale, County Louth, in 1798, he arrived in New Orleans in 1835, and became the “Father of Greek Revival Architecture” in that city. His two masterpieces were the Saint Charles Hotel and City Hall, later renamed Gallier Hall, which was believed to be one of the most distinguished Greek revival buildings in the world. When the Saint Charles Hotel opened for business in 1837, it was believed to be the most extravagant in the world. In his later years, Gallier traveled extensively, and died in a shipwreck in Cape Hatteras, off North Carolina. His son, James, Jr., also became a famous architect in New Orleans and is best remembered for designing the luxuriously famous “Old French Opera House” on Bourbon Street.

Famine Immigrants

Irish immigration to New Orleans and the United States reached its apex with the arrival of the Famine immigrants between 1845 and 1855. During that period, over 50 percent of all immigrants entering New Orleans, and one-third of those entering the United States as a whole were Irish. By 1860, 15 percent of the population of New Orleans were Irish born.

Before the Famine in 1845, passages to America were usually paid by individuals themselves. Prior to that time, New Orleans had only one immigrant passage office. As a result of the Famine, at least 10 additional ones sprung up. Relatives or friends could

book a passage in advance through these agents for new-comers. A majority of the Famine immigrants came via Liverpool, but some came directly from Ireland. Weakened by starvation, they were crowded like cattle onto old passenger vessels, which lacked proper sanitation and food. The brokers in Liverpool often cheated the emigrants by exchanging English money for fake American notes. A large section of the immigrants contacted typhus in flop houses in Liverpool where they had stayed for a night or two before embarkation. Others caught the disease on the ships. Many of the dead were parents whose young children, having survived the ordeal of the sea, arrived in New Orleans with no place or no one to go to. Others, unfortunate enough to arrive during the summer months when yellow fever was rampant, succumbed to the disease. During the first week of May, 1849, the Crescent City registered 225 deaths from yellow fever of which 214 were Irish.

On the dock in New Orleans, the counterparts of the Liverpool “sharks” were waiting to exploit the starving immigrants by selling them fake permits to allow them to disembark. Often they were taken to overcrowded boarding houses and robbed while they were asleep. Madams and panderers cajoled young girls into houses of ill repute. Many others, penniless and starving, were forced to wander the streets or crowded into Charity Hospitals whose nuns were mostly Irish-born.

On February 4, 1847, an Irish relief committee was formed in New Orleans to help the destitute in Ireland. The governor of Louisiana, Isaac Johnson, and the mayor of New Orleans, A.D. Crosman, were members of this society, which collected $50,000 during the first six months of its existence, and sent four shiploads of grain to Irish ports. However, it was not until December, 1849, that a magnanimous effort was made to help the Famine immigrants when the Irish Union Immigrant Society was formed. Its first president was John Prendergast, editor of a local newspaper, The Orleanian.

The principal aim of the society was to purchase cheap farmland in the western states and settle it with Irish immigrants, a plan which never reached fruition. The society was, however, successful in sending many of the destitute to other cities where they received some assistance. Additionally, it established a shelter on Spain Street for drifters, where they received free medical attention. Ironically, most of the society’s support came from working-class Irish, and Prendergast castigated the affluent Irish in his newspaper for their indifference.

Despite the Famine the Irish in New Orleans were still participating in the growth of that city. In 1850, the Irish constructed a wagon road one and a half miles long, from the mainland to Avery Island in southwestern Louisiana, and built the Opelousas Railroad through swampy terrain in that same region. Two new Irish churches, St. Alphonsus and St. Peter and Paul, were dedicated in 1850, and a third, Saint John the Baptist, in 1851. The worst yellow fever epidemic in the city’s history struck in 1853, taking the lives of 12,000 inhabitants, 4,000 of whom were Irish.

New Orleans had many Irish organization during the periods of mass immigration, the best known being the Hibernian Society, the Emmet Club, and the Shamrock Benevolent Society. Three Irish newspapers, The Emerald, The Immigrant, and The Catholic Standard, existed at various times but were never successful. There were three Irish-born editors, J. Prendergast, J. Maginnis, and T. Burke, of local newspapers in the city between 1820 and 1860. Their papers carried Irish news regularly, plus clippings from Irish newspapers at home. This probably accounts for the demise of the local Irish papers.

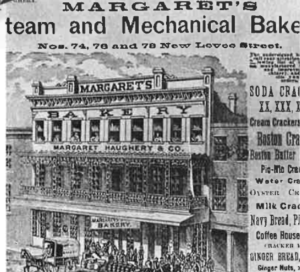

Margaret

Margaret Gaffney Haughey, born in Cavan in 1813, was one of New Orleans’ best-loved women. Margaret came to Baltimore at the age of five with her parents. They died when she was nine, and Margaret was brought up by a Mrs. Richards. At 21 she married a Charles Haughey, and they left for New Orleans, where a daughter was born. Haughey’s health failed, and he died after a sea voyage in a vain effort to recuperate. Their only child also died, and Margaret, left penniless and alone, devoted herself to helping orphaned children, of which New Orleans had an unusually large share. By 1840 she had succeeded in raising funds to erect St. Theresa’s Asylum on Camp Street. In 1859 she became the owner of a bakery then nearing bankruptcy. Margaret’s shrewdness and keen business sense soon put the bakery on a paying basis. Using much of the profits of her enterprise, she did an ever-increasing amount of charitable work, and at her death in 1882 three prosperous asylums owed their origin and success to her untiring energy and generosity — St. Vincent de Paul, the Female Orphan Asylum, and St. Elizabeth’s Asylum. In her will she left her business worth about $30,000 to New Orleans orphan asylums: Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish. She signed her will with an X; she had never learned to read or write.

Today a monument sculpted by Alexander Doyle, who did the figure of Robert E. Lee atop the column at Lee Circle, stands in a little park bounded by Camp, Prytania, and Clio streets. It is white marble and simply says “Margaret.” It was paid for by public subscription.

The Know Nothings

The election of Edward White as governor in 1835 caused growing resentment towards foreigners and Catholics by a certain group of nativist Americans who claimed they were passive spectators while others created their destiny. As time went by the Irish incurred the entire wrath of this rabble known as the “Know Nothings,” egged on by two bigots, John Gibson and William Christy, plus a rag newspaper, The True American. The nativists secretly armed themselves and carried out several killings. By striking fear into the community as a whole, they were successful in keeping the voters away from the polls and eventually taking control of the city. They got an added boost in 1854, when the Whig Party disintegrated over the slavery issue. Many of the slave-owning Whigs joined the “Know Nothing Party.”

During the elections of March 1854, violence, intimidation, and fraud were widespread. Two Irish-born policemen were shot dead. The “Know Nothings” vilified the police force in general, and the police chief, Stephen O’Leary, in particular, claiming that they were responsible for keeping the Democratic Party in power. The Irish-backed Democratic mayor, John Lewis, won the election. However, all other major city offices were captured by the “Know Nothings.” This gave them partial control of the city. During the first 10 days of September, 1854, the “Know Nothings” went on a rampage, shooting up Irish coffee houses and bars. On September 11, 1854, the Irish retaliated, and in the ensuing melee, two Irishmen, Kane and Boylan, were shot dead. The mayor then hired armed citizens, mostly Irish, to patrol the streets and order was restored temporarily.

The election of June, 1856, was amongst the most violent in the city’s history. Terror worked for the “Know Nothings” and a majority of foreign-born voters, as well as many natives, were afraid to be seen in the vicinity of the polls. As a consequence, the “Know Nothings” swept the election. They then set about the task of removing the Irish from city positions beginning with the police force. All Irish-born teachers were removed from public schools and replaced with native-born Americans, many of whom were illiterate. Even street cleaners who were Irish born were removed from the city payroll. Irish-born children of the Famine immigrants were regularly insulted in class by the new pseudo-instructors.

A quixotic idea developed among the New Orleans Irish at this time to relocate south of the Rio Grande in Mexico. They even petitioned the government of that country for permission to settle there. But the idea never got past the planning stage. As fate played its part, another incident would come along causing the lights to go out quickly for the “Know Nothings” and an Irishman would again take control of Louisiana with the same powers as O’Reilly had some 90 years before. Additionally, an Irish American would be installed as mayor of New Orleans.

The U.S. presidential election of 1860 was the most crucial in the nation’s history. The Democratic party had now split in two, like the Whigs, over the slavery issue. Four parties contested the election. The Republicans, led by Abraham Lincoln, were opposed to slavery. The Southern Democrats, led by John Breckenridge, were pro-slavery. The Northern Democrats, led by Stephen Douglas, were against slavery in general. The Constitutional Union Party, led by John Bell, was composed of slave owners, bigots, and “Know Nothings.”

John Slidell, as organizer for the Southern Democrats, made a vain attempt to garner the Irish immigrant vote, but admitted failure, feeling they had a proclivity for Lincoln and the Republicans. However, the main issue as far as the Irish were concerned at that point in time were the “Know Nothings.” The Irish, therefore, voted overwhelmingly for Stephen Douglas, the first major politician to consistently denounce that organization. Lincoln’s victory at the polls was followed shortly thereafter by the American Civil War.

Ironically, most of the Louisiana Irish fought for the Confederacy, and many of them went as far away as Virginia to fight at the front.

Several Irish militia units existed prior to the Civil War, the most notable being “The Emmet Guards” and “The Montgomery Guards.” The latter was called after Michael Montgomery, a general in the American Army during the Revolutionary War. Most of these militia units joined Louisiana regiments, the majority of which had two or more Irish companies. Additionally, many new Irish military units were formed around prominent citizens who received commissions from the state governor. The two best known of these companies probably were “The Sarsfield Guards,” under Captain O’Hara, and “The Southern Celts,” under chief of police, Stephen O’Leary.

In October, 1861, many of the older Irish leaders complained about a disproportionate number of young Irish being sent to the front. John Maginnis, editor of The True Delta, a daily newspaper, publicly accused the state governor of dispatching the young Irish “with readiness” to fight the country’s battles, while placing his friends in safe positions at home. Maginnis urged Irishmen to join home guard units; and in late 1861, the Louisiana Irish Regiment was formed with two wealthy Irishmen in charge: P.B. O’Brien, as colonel, and W.J. Castell, as lieutenant colonel. They never saw action. The Union Navy broke through the boom of the Mississippi and had New Orleans at its mercy on April 24, 1862. On April 25, the city was surrounded and occupied by Union soldiers for the next 14 years. The new military government suppressed the criminal element and put the unemployed to work cleaning the city. Subsequently, yellow fever went into decline and was eventually eradicated altogether.

A congressional act of 1867 placed Louisiana under occupation by Union soldiers under the command of General Philip Sheridan. Born in County Cavan, Sheridan distinguished himself in the Civil War. Streets, highways, bridges, cities, counties, and mountain peaks, across the United States, bear his name. However, as a northern general, and head of an army of occupation, he was never a popular figure in New Orleans where he administered the Act of 1867 with an iron fist, denying half the white citizens of Louisiana the right to vote while extending suffrage to all adult blacks. Under this system, a northerner was elected governor, and a mulatto became lieutenant governor of Louisiana. Two Irish Americans were installed as military mayors, H. Kennedy (1865-1866), and J.R. Conway (1868-1870). Irish immigration ended in 1860, and the next wave of immigration would be from Italy. In time, the Italians would become and probably still are the largest ethnic group in greater New Orleans. Military occupation of the city ended in 1874, the same year as the “Know Nothings” attempted a comeback under the banner of the “White League.” Their hostility was now directed at Union occupation. They overpowered the New Orleans police and installed one of their men as governor and another as mayor. Their victory was short-lived, and they were quickly thrown out by Union soldiers, bringing their era to an end.

Four Irish Americans were elected as mayor after military occupation. William J. Behan served from 1882 to 1884, John Fitzpatrick from 1892 to 1896, Andrew McShane from 1920 to 1925, and Arthur J. O’Keefe from 1926 to 1929.

Epilogue

Sadly, the Irish presence in New Orleans today seems to be relegated to the once a year St. Patrick’s Day celebration of green beer and leprechauns. Their triumphant history is visible only in graveyards and in the statue of “Margaret.” If readers know otherwise, please let us know. — Editor

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the May/June 1994 issue of Irish America. ♦

Leave a Reply