After 20 years, Paul Hill wins the fight to clear his name.

Close to four million Americans have seen In the Name of the Father, the movie which chronicles the events of 20 years ago in which Paul Hill, Gerry Conlon, Paddy Armstrong and Carole Richardson were convicted of the pub bombings in Guildford and Woolwich that killed seven people. The only evidence against them was their own uncorroborated confessions. Paul Hill, then 21, was sentenced to serve the rest of his natural life in prison–the longest sentence ever handed down by a British court. Hill, and the other three members of the Guildford Four, always maintained their innocence, saying that they had been terrorized by the police into signing false confessions. In 1989, the Court of Appeals finally quashed their convictions, and the four were released after serving 15 years. The Crown admitted that investigating officers had lied at the original trial; however, no official inquiry has ever brought anyone to book for the false imprisonment of the four and of others who were jailed as co-conspirators: Conlon’s father, who died in prison, and his aunt Anne Maguire and her family.

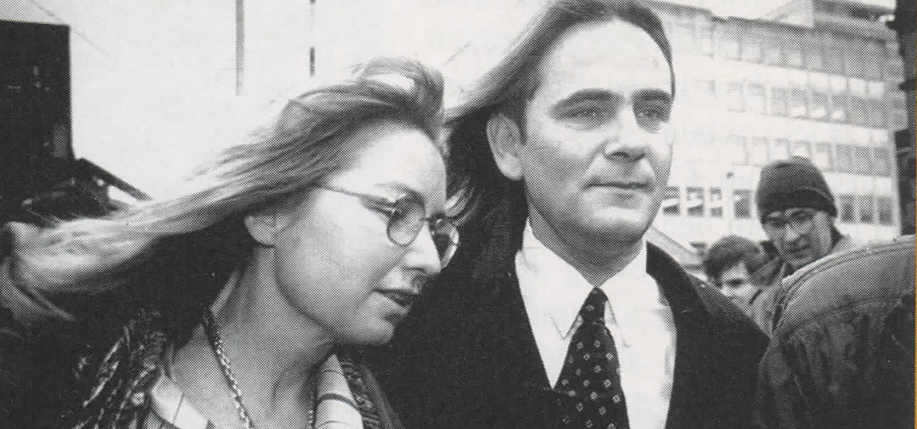

Those who have seen the movie may not be aware that Paul Hill had also been convicted, again on uncorroborated evidence, of the murder of a former British soldier, Brian Shaw. Hill took his case before the Appeals Court in Belfast recently, and testimony was heard from police officers who confirmed that the Guildford Four were not treated in a “normal manner” upon their arrest. All charges were dropped against Hill.

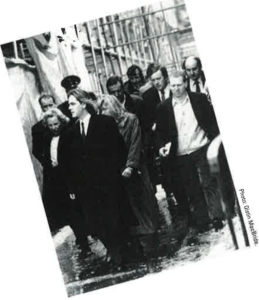

Because of his marriage to Courtney Kennedy, daughter of Robert and Ethel, Hill’s appeal turned into an international media event. Good Morning America, 60 Minutes, and other major news teams descended on Belfast during the appeal, and again when the decision was announced by the court on April 21.

PATRICIA HARTY talked to Paul Hill and his wife, Courtney Kennedy, in County Clare, where they have been living for the past months. Although they would not know the decision by the court for another two weeks Hill was confident that his conviction would be quashed.

Patricia Harty: How did you feel about being back in court in Belfast?

Paul Hill: I felt a bit traumatized by it. I had a sense of deja vu. It was painful having to sit there and be quiet whilst being called a murderer again, and a ruthless liar again by the prosecution. Having to walk into court and sit and look at three judges who in the normal course of events, if there hadn’t been the media spotlight that there was, would have knocked down everything that the defense put up, and backed up everything that the prosecution said. Northern Irish legal people said to me that they had never, ever seen these judges rock back on their heels in the way that they did, which is hurtful to me, because I am free, but what happens to the young man from West Belfast who is brought before that court next week with just his mother and father and two local reporters sitting there?

Patricia Harty: Would your appeal have gotten as much media attention if you weren’t married to Courtney Kennedy?

Paul Hill: It’s an insult to justice that all the media was there simply because of In the Name of the Father and the Kennedys. How dare anyone say that my mother-in-law and sisters-in-law and brothers-in-law shouldn’t have come to sit beside me in court? What would any other family have done? What would have been the adverse publicity if they hadn’t come? They would have said the Kennedys have abandoned their son-in-law in Ireland.

I also realize that the Kennedys are a target for many sections of the British media because they have been outspoken critics of British policy in the North. Senator Ted Kennedy spoke out against internment in the very early seventies, and the brutality in the interrogation centers, and Joe [D-Mass.] has continually spoken out. So, it’s a family that will always be knocked down, certainly in the British media.

Patricia Harty: So the media weren’t there to see justice dispensed?

Paul Hill: Justice played no part in all these television crews rushing to Belfast, being concerned investigative journalists, bullshit, it had nothing to do with that. Where were they in the Ballymurphy Seven case? There were young people standing outside with placards [protesting the Ballymurphy Seven] when all these camera people were there, I didn’t see any of those shots on television. I didn’t see the media falling over themselves to say this is still going on in Northern Ireland.

The only evidence against the young men in the Ballymurphy Seven case is their own confessional evidence. They have documentation, they have proof, of beatings that took place in the interrogation center.

Patricia Harty: How important is it that you win your case?

Paul Hill: The importance of me winning my case, and the reason why they fought it so ferociously, is, if I create legal precedence in the North, I bury the chance of the prosecution ever sending another person to prison on uncorroborated evidence.

Patricia Harty: You were released in October, 1989. Why did it take so long to get to the appeal?

Paul Hill: Several times during the course of the last three years they tried to rush the case into court but my attorneys said we were not fully prepared to mount a strenuous defense because there was 27,000 pages of documentation that we had to go through, and other documentation that we were trying to get at. And in December of ’93 we received documentation from six police officers. Three of the police officers mentioned a gun incident in Guildford police station. One of them mentions it quite specifically on the 28, which was a very important date for me because I was the only person in custody on that date.

That police officer testified that he looked along the cell corridor and he saw Constable Gerald Queen standing in front of my cell with his revolver pointed into the hatch of the cell door, and ‘he had an expression on his face like a leer and there were at least two clicks,’ i.e. it dry fired twice.

I have said from the moment of my admission into prison in 1974 that I was threatened with firearms on several occasions. The prosecution’s case all along was that that was complete nonsense. Yet here we have three police officers who said that it happened.

Good God, these were police officers with 30 years experience of breaking down the toughest criminals–we were putty in their hands.

Patricia Harty: How important is the movie In the Name of the Father?

Paul Hill: If the people who go to see In the Name of the Father leave the cinema with a thought and a fact, the fact being that this happened to completely innocent people, and the thought is that no one was ever held accountable for what happened to those innocent people, then I don’t care how that gets across, as long as they leave with that message. And I think that most people are leaving the cinema with those two things in mind.

And I think that a lot of the journalists who condemned In the Name of the Father because of the inaccuracies that were in it have one bloody cheek. Where were those people when we were languishing in prison, many years ago? Where was their concern about the truth when we stood in the Old Bailey and were told that we were terrorists who had killed seven people?

Patricia Harty: Did you yourself have problems with In the Name of the Father?

Paul Hill: One of the problems I had was that I was portrayed eating in the kitchen of Anne Maguire’s house; it never happened. I was never in Anne Maguire’s household, which is important, because Anne Maguire and the Maguire family were arrested as the result of [alleged] contamination of a towel in their kitchen, i.e. someone who had been in their kitchen had nitrogyclerine on their hands and wiped their hands on the towel. That was one of the explanations that the British still clung to, the ‘there’s no smoke without fire’ syndrome. If the Maguires’ were innocent who contaminated the towel?

So, In the Name of the Father I’m in their kitchen. Jim Sheridan [director], when I spoke to him about it, said, ‘Paul, if there was anything I could change about In the Name of the Father in that respect it would be that you weren’t in Anne Maguire’s kitchen.’

Patricia Harty: After 15 years in prison you must have had problems adjusting?

Paul Hill: Perhaps I’m a bit better now, but I still find it a little bit difficult that things I do now have to have a joint decision because I’m married. For many, many years of my life I made my own decisions. And when I made my own decisions I was opposing a whole bloc of people. I didn’t care what they thought about my decision. When I was in prison if I said I didn’t want to work, I didn’t work. If I said I didn’t want to eat, I didn’t eat. If I didn’t want to exercise, I didn’t exercise, and there was no going back on that once I said that was what I was going do. If you do that for a period of fifteen years you condition yourself. You don’t really think, ‘I’m not in prison now, I have to interact here.’

Patricia Harty: You did have one rather nice job that I know of.

Paul Hill: Yes, I was consulting on a movie called Blown Away, which is coming out this year. Having watched Patriot Games I harbored a suspicion that Hollywood was not prepared to portray Northern Ireland in a proper light, so I had reservations about getting involved. I really was very stand-offish about it at the start.

Initially, I was going to Boston for four days to consult with actor Tommy Lee Jones, and the producer and director. It was abundantly clear from my conversation with the producer, John Watson, a nice guy who had done Backdraft and Robin Hood, that Tommy Lee was expecting me to do it and unless I was prepared to do it he didn’t really want to do it. We arrive at the Charles Hotel and Tommy Lee sits back and looks at me, and says, ‘Paul what do you think this movie is about?’ I thought the original script was poor and I said, ‘Well, I think the script is completely poor. There are a lot of things in there I don’t agree with. It’s a very stereotypical vision of Irish people,’ and he said, ‘O.K. what do we want it to be about?”

He was reading Ten Men Dead [about the hunger strikes] and Bobby Sands’ prison diaries, and I was prepared to help him, to tell him what it was like to be in prison, what it was like to grow up in Belfast, and what makes people like [the] Tommy Lee Jones [character] function. He was very fired up about this and we went off and did a couple of nights shooting. Then the producer asked me how I felt about spending the rest of the time in Boston, which was about four or five weeks, because Tommy Lee wanted me to stay. I said it was fine with me. I worked with Jeff and Lloyd [Bridges] and at the end of the shooting in Boston Tommy approached me and said it would be of great benefit if I went to L.A., and so we then went to L.A. for a further nine weeks.

Patricia Harty: What’s the movie about?

Paul Hill: It’s a movie about two young men who grow up in Northern Ireland and become involved in political violence. They engage in an attack on a military patrol in a country area of Ireland. Tommy Lee Jones is hiding in an alleyway and this gunfight happens as he is about to plunge this bomb, and Jeff Bridges who is watching the movements in the square runs up and tries to stop him. Tommy Lee plunges it anyway, the bomb explodes, and a few of his friends and some other people get killed.

Jeff Bridges escapes and goes to Boston, changes his identity, marries a Boston girl, and becomes a member of the Boston bomb squad. Tommy Lee Jones spends 15 years in prison, eventually kills a guard, escapes, goes to America where he is sitting in a bar one night and he looks at the 7 o’clock news and he sees Jeff Bridges defusing a hoax bomb in Boston, and that’s basically where the movie starts.

I had a problem with maybe certain people saying to me, well, you are saying innocent people get killed and you lend your name to that type of thing. I can’t be accused of subverting reality; believe it or not, innocent people are being killed, that’s the reality of it, but I also wanted to get in there the reason why people were prepared to accept that innocent people get killed, because it is a war. There is one scene where Tommy Lee Jones is talking on video and I won’t tell you what he says but I think it is of immense importance and it goes right to the core of everything that’s happening in the North of Ireland today, and there is another scene where he is on the telephone to Jeff Bridges, and he enters into an explanation of why people are prepared to kill people in the North of Ireland. So the counter balance is there.

Anyway, I arrive out one morning to a lot in the Hollywood Hills, and it’s very, very Irish. They had spent three or four days and massive money doing it up, and they thought they had it done perfectly. The director asks me if everything looks o.k. I say, ‘it looks a bit strange,’ and I point out that the truck they are using to bring the bomb into the square has the steering wheel on the wrong side. He says, ‘shit, what else is wrong?’ and I say ‘all the potatoes up there are California reds.’ So, he says, ‘Jesus, Paul, what else?’ We walk about and there are two cows on the set, and I say, ‘that’s a French Fresian.’ He says, ‘what do you mean a f…ing French Fresian?’ I had him on the cow. [Laughs] He was going to change the cow.

Patricia Harty: What about your own movie?

Paul Hill: It’s in the early stages. I’m kind of excited about the prospects, and actually, this will be completely different from In the Name of the Father. This will begin where Gerry’s movie ended, with the present phase of my life which began with my release from the Old Bailey.

The people that are involved are very concerned about the fact that many young men are still in prison on the basis of what is not acceptable in any court in the whole of Europe. And I think that they are quite prepared to condemn that, and to show it as it is, otherwise I would not engage in letting them do it.

Patricia Harty: Do you think the Nationalist people in the North have been demonized to the point where people say that they are all psychotic?

Paul Hill: I came from a community in West Belfast where kids played in the streets until 12 o’clock at night. Where a sexual molester of a child would have been burned at a stake. The worst crime I ever heard of in West Belfast was of someone’s gas meter being broken into. That was up until 1969. So where did this psychotic strain come from? Did we all become psychopaths after the British army arrived? And if we did, why?

Patricia Harty: How important is the Irish-American lobby?

Paul Hill: It’s incredibly important. The Irish-American vote, especially in the last election, proved a big turning point. They gave their vote, and I think that they should stand up with one voice and say ‘we’ve paid our dues and we want the goods produced.’ Certain promises were made. Some have been fulfilled — grudgingly, but they’ve been fulfilled. We want to see the rest of the package that we were promised.

I do think that the visa to Adams, though it was condemned in many quarters, has to be applauded, because whether you agree with him or not, Gerry Adams has a legitimate right to express the frustrations of a very large number of people in Northern Ireland. Gerry Adams is probably the only man in Northern Ireland who has the credibility in the nationalist community to pull off a peace package — I really believe that.

Northern Ireland has no more and no less baggage than the Middle East. And if the President of the United States can stand on the White House lawn and shake hands with two people who were engaged in bloody warfare in the Middle East, then he can certainly ask Gerry Adams to America.

Patricia Harty: Since you’ve gotten out of prison in 1989 you’ve done a lot of work with human rights groups.

Paul Hill: I would have a big dilemma if someone rang my doorbell at three in the morning and said, ‘can you please help me, my son is in prison,’ but I also realize that I have my own life to lead. I’m an individual and I can’t afford financially to do that. So I put myself forward for groups who could afford to champion these people’s causes. Not that I have ever taken money for speaking anywhere. If I’m going to speak, I’m going to speak from the heart, not because I want financial reward.

I went to Australia for a fellow called Tim Anderson who was serving life in prison on a trumped-up charge. I addressed the Australian Bar and debated his case on television. When I got back to New York there was a message from him on the answering machine, saying he had just been released. It was a nice bit of personal gratification to have helped get someone out of prison on the other side of the world, someone I had never heard of two months previously.

I did some extensive work for Amnesty for a Survivors’ Committee. It was very intense because I was with a group of people who had undergone great traumatic stress. One was Chinese, one was Nicaraguan, one from El Salvador, and one from Chile. One woman had lost her husband, been raped several times, and two of her children had disappeared.

Trying to interact with these temperamental and distraught people was very difficult and draining. They would clash on certain aspects. They would all accuse Amnesty of being too soft. I felt Amnesty wanted to help these people, so we put forward a group who went to Vienna for last year’s human rights world conference.

I did several other things with Amnesty. I supplied information on lots of stuff, and spoke to them lots of times on the North; collusion was one of the subjects.

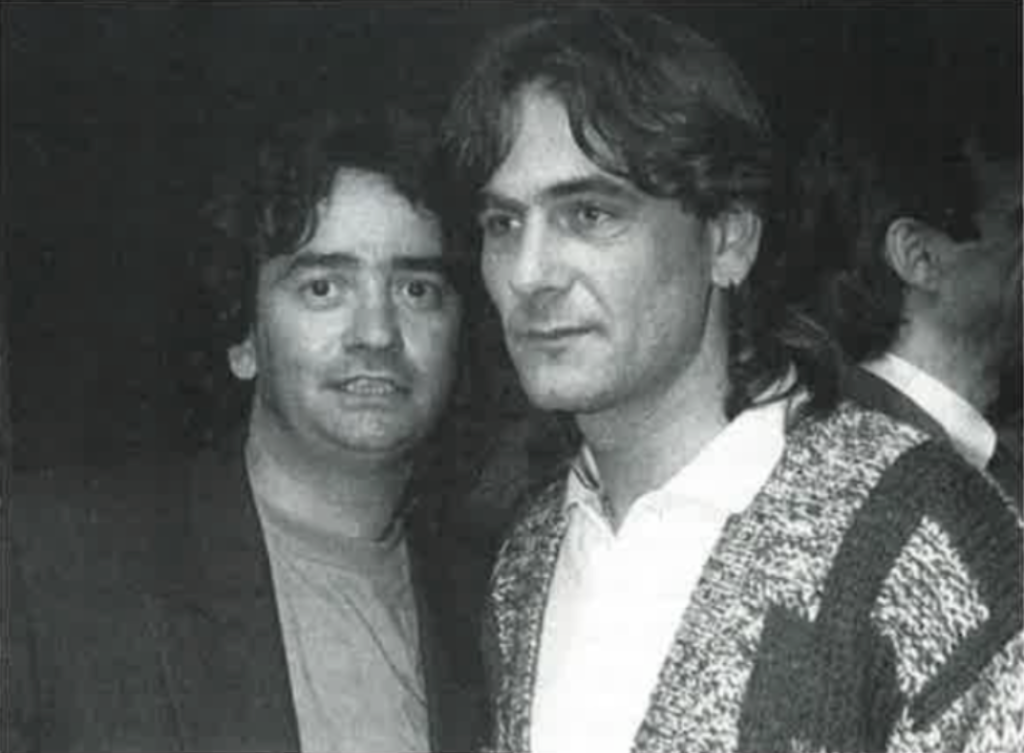

Patricia Harty: Can you tell me how you met Courtney?

Paul Hill: I met Courtney’s mother when I addressed a human rights caucus in Congress on behalf of the Birmingham Six with Gerry [Conlon]. She was impressed with how we were, and I went to a cocktail party with her afterwards. She asked me to go and visit Courtney when I got to New York, because Courtney had broken her neck skiing and was confined. So, I did, and Courtney [wearing a neck-brace] came to hear me speak the following night when I was addressing the Brehon Law Society.

When I returned to London she came to visit. A couple of months later we went to Spain, and a couple of months later again, we went for a holiday on the West Coast. Then it became a bit more serious. She was very helpful in the human rights field, and though we had very different backgrounds, we had a lot in common. We had suffering in common. I also felt that here was a family who had, but cared about the have-nots, a family that was prepared to stand together, a family that had been vilified in the same manner that I had been vilified in the press.

Patricia Harty: Courtney, was it love at first sight?

Courtney Kennedy Hill: Yes, I would say it was for me anyway, not so much for him. I was very impressed with him and thought he was bright and fun to talk to and had a great sense of humor. I went to listen to him speak a day or two after meeting him and I thought he was an amazing speaker, especially for someone who probably didn’t have a lot of practice. He was very natural and very clear. He got all his points across and had the audience in the palm of his hand. I was just amazed by him.

Patricia Harty: What was your interest in Northern Ireland before meeting Paul?

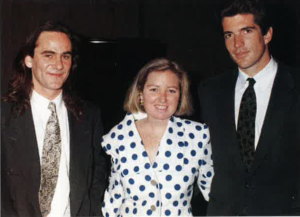

Courtney Kennedy Hill: I’ve been coming to Ireland most of my life, and I’ve always been interested in human rights, especially in Northern Ireland. I came over here in 1988 with my brother Joe. We went around Belfast and Derry and Newry, and during that visit we also visited with Gerry Conlon’s mother. When we got home, through Joe’s office we worked in whatever way we could to help with their release, along with a lot of other people who got involved at that time.

Patricia Harty: You must be proud of the way your family supported you both?

Courtney Kennedy Hill: Well, I am, certainly, but I do think an awful lot was made of that in the press, and as Paul said earlier, somehow there was no way we could win, some people would have said they were parading, others would have said why aren’t they there? Both Paul and I are very close to my mother, and my brothers and sisters, and the other in-laws and it seemed only natural for them to be there, as it was for Paul’s mother and his brother and other family members who are my in-laws. I think it would be strange if a family wasn’t there for somebody going through what Paul was going through.

Patricia Harty: You’ve spent the last couple of months here. What are your impressions?

Courtney Kennedy Hill: My impressions are wet and windy and cold, [laughs] but that’s only for the weather. The people are warm and loving and kind and fun and it’s beautiful.

We go for lovely long walks, there are beautiful walks here. We go riding, and we go for drives around the country and visit different parts. We have been very lucky that we have made a lot of friends through coming over here the last couple of years, and we go visiting them. but I think the nicest thing is the walks and the riding, and we tried pitch and putt a few times but Paul was pathetic [laughs]. We are very happy here.

Patricia Harty: But you’re looking forward to your return to the States.

Courtney Kennedy Hill: Well, our lives have been on hold, and, yes, I am looking forward to seeing my family, but I feel equally at home in both places.

Paul Hill: Obviously, the most comfortable scenario for the both of us is that we live in America. I like New York, I love New York, it’s a vibrant city. If you have a dreadful hangover in the morning you can open your window and the buzz of the city will just draw you in. So any city that can cure a hangover is a good city, and I don’t mean go back to the pub, I mean make you want to function. But I also like serenity. I love Boston and I also think that it is a sign that I’m getting old that I love houses on the waterfront.

Patricia Harty: Well, down here in Clare you are certainly on the waterfront.

Paul Hill: You know, a little cottage that we can come back to in Connemara or certainly in the west would be ideal. We love Doolin. I love music and quaint places where people will come over and shake your hand, or nod, or just wink at you but they will leave you alone. And I love to listen to the conversations of these people who have lived in this barren environment for many years, and know how intelligent they are, how humorous, and how rich their method of communication is. They say very little but they say it in such a way that it means a lot. You certainly know where we got our good playwrights and our good poets from. This is not a conversation, this is a talking picture because when you have a conversation with someone you don’t actually think about what that person is saying to you, you can actually see it with them and that’s the richness of the Irish language.

Courtney Kennedy Hill: As beautiful as it is, there’s a little village just up behind us which is called the deserted village, or the Famine village. It is a tiny little place in terms of size but hundreds upon thousands of people lived there and because of the Famine they all either left or died. You can go up there and you can feel the life that must have been there.

Paul Hill: We should by all means remember the people who died in the Famine but never be sad about that, Courtney, be proud about that because all those people who left around that time and went to America actually paved the way for the young Irish who are there today, they built the power base that affluent Irish Americans control today, so we didn’t lose anything by that. The Famine was another mismanaged involvement with the Irish people that the British carried out. We became more powerful than we would have ever become had they not let the slaughter of the Famine continue.

Patricia Harty: Courtney, I’ve seen the way people around here talk to you about J.F.K. and your father.

Courtney Kennedy Hill: I find it very kind when people come up to me and say how much they admired my father and my uncle. It’s a testament to the great work that I think they both did–I’m very proud of them myself so I am glad that the Irish are as well.

Patricia Harty: Do you see a future for yourself in politics?

Courtney Kennedy Hill: No, I don’t think so, but I’ll continue working on human rights in Ireland.

Patricia Harty: I think one Kennedy member we can all be proud of is Ambassador Jean Kennedy Smith.

Courtney Kennedy Hill: Yes. Both Paul and I are very proud of what she has been doing and I think it is nice to have a member of our family here, and I think it is also nice to have such a great house in Phoenix Park when we go up to Dublin [laughs].

Paul Hill: And also to have someone here who has the moral courage to go to Belfast and sit in a Diplock court and watch the trial of seven young men. When you have an ambassador of that caliber, Irish Americans are being well represented.

Patricia Harty: Courtney, if your father was alive, do you think he and Paul would get on?

Courtney Kennedy Hill: All I know is what I think, and I think that Paul and he would have adored each other and I’m very sad that they were never able to meet, as I am sad I was never able to meet Paul’s grandparents who sound like amazing people themselves, the Cushnahans.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the May/June 1994 issue of Irish America. ♦

Leave a Reply