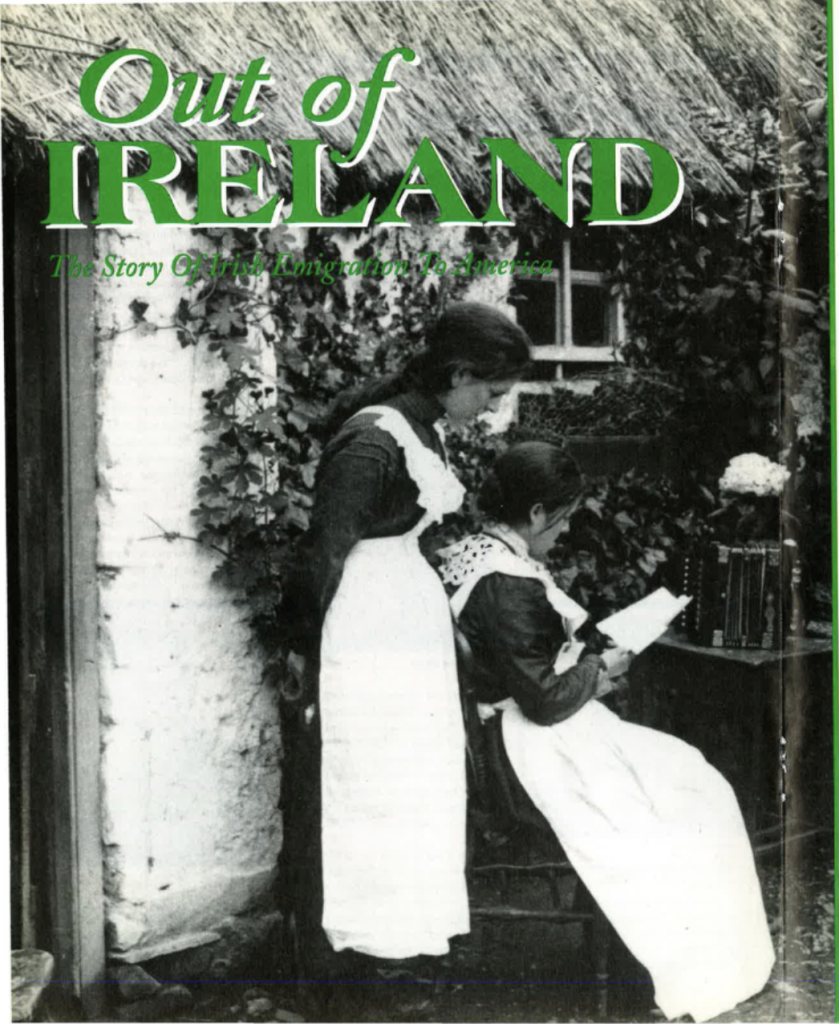

Out of Ireland, a documentary film by Academy Award-winning filmmaker Paul Wagner, had its first public showing at the New York Lincoln Center Irish Film Festival in June, and will air on PBS television stations sometime this fall or next spring.

Using as its primary source the remarkable memoirs and letters written by and to Irish immigrants in America, from Kerby Miller’s award-winning 1987 book Emigrants and Exiles, Out of Ireland provides a fascinating and moving portrayal of the history of Irish immigration to the United States in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries. It is a powerful story that speaks to the heart of their 44 million descendants, and to anyone who has ever dared to pursue a dream. Accompanying the documentary is a book by the same name published by Elliott &Clark, due out in August. The following is a selection of letters and photographs from Out of Ireland reprinted with kind permission of the publishers.

On January 26, 1870, a young Irish immigrant named Maurice Woulfe sat down in his army barracks at Fort Russell in the unsettled wilds of Wyoming Territory. Sergeant Woulfe wrote the following letter to his brother in Cratloe, County Limerick, in the southwest of Ireland:

Dear Brother Michael,

I received your welcome letter this afternoon I was very glad to hear that you and all the family in Cratloe were well. Michael, I am in first rate health I was never better in my life. This Rocky Mountain air agrees with me first rate. I have everything that would tend to make life comfortable. But still at night when I lay in bed, my mind wanders off across the continent and over the Atlantic to the hills of Cratloe.

In spite of all I can never forget home, as every Irishman in a foreign land can never forget the land he was raised in. Every stone, gap, and field in Cratloe and its surroundings are as clear in my mind as when I was home. I sometimes imagine I am on top of Ballaugh near Daniel Riordans, looking over upon Cratloe and upon the old lime kiln where I used to play ball in my youth. But alas! I am faraway from them old haunts. But still I imagine that I will see Cratloe once more. But if I do I guess all things will be changed

I must close and remain as ever your devoted brother,

Maurice H. Woulfe.

Write soon.

Maurice Woulfe was only one of the 7 million men and women who came out of Ireland to America in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries. Yet this letter to his brother Michael captures the paradox of the Irish immigrant experience: “I was never better in my life,” but “in spite of all I can never forget home.”

In 1825 Thomas Barrett and his wife, Bridget, took several of their younger children with them to Canada, but left behind an older daughter, Mary, who married Michael Rush, a laborer with a few acres of land. Unfortunately, Mary Rush’s decision to stay in Ireland would have fateful consequences.

On September 6, 1846, the illiterate but desperate Mary Rush dictated a letter, perhaps written for her by the parish priest or the local schoolmaster, to her parents in Quebec, Thomas and Bridget Barrett, whom she had not seen for more than 20 years:

Dear Father and Mother, Pen cannot dictate the poverty of this country at present. The potato crop is quite done away all over Ireland there is nothing expected here, only an immediate famine. If you knew what danger we and our fellow countrymen are suffering, if you were ever so much distressed, you would take us out of this poverty isle. We can only say, the scourge of God fell down on Ireland, in taking away the potatoes, they being the only support of the people. So, dear father and mother, if you don’t endeavor to take us out of it, it will be the first news you will hear by some friend of me and my little family to be lost by hunger, and there are thousands dread they will share the same fate. So, l conclude with my blessings to you both and remain, Your affectionate son and daughter, Michael and Mary Rush For God’s sake take us out of poverty, and don’t let us die with the hunger.

Thomas and Bridget Barrett, unfortunately, had no money to send to their desperate daughter. The Barretts’ farm produced sufficient food for their family, but it generated no cash income. It was located far from any markets, the soil was thin and rocky, and most of it was still covered by dense forests. The Irish Canadian community of St. Columban was almost as poor as the Irish townlands its inhabitants had left behind.

As a last resort, Thomas Barrett appealed for help to his parish priest, who in turn begged for assistance from the British Canadian authorities. It was proposed to Lord Elgin, Canada’s Governor General, that relief funds from the British treasury be used to bring out from Ireland Mary Rush’s family and the other poor relatives of St. Columban’s inhabitants.

Unfortunately, both Lord Elgin and his superior in London, Sir Charles Trevelyan, the director of the British government’s Irish relief measures, rejected this and other proposals for government-assisted emigration from Ireland. After all, wrote Trevelyan, “The great evil with which we have to contend, is not the physical evil of the famine, but the moral evil of the selfish, perverse, and turbulent character of the Irish people.”

Mary Rush’s anguished appeal for help went unanswered, the Rushes never reached St. Columban, for there is no trace of them in that community’s detailed records.

Hundreds of thousands of Irish in North America did respond to such pathetic appeals and sent money or passage tickets. As a result, during and immediately after the Great Famine, more than 2.5 million Irish emigrated. In only ten years, nearly 30 percent of Ireland’s population left the island.

A few days after arriving in Buffalo, Daniel Gulney and his friends collectively wrote a letter to those still at home in Ireland.

August 9, 1850

Dear Mother and Brothers,

We mean to let you know our situation at present. We arrived here about five o’clock in the afternoon of yesterday, fourteen of us together, where we were recieved with the greatest kindness and respectability by Mathew Leary and Denis Danihy. When we came to the house we could not state to you how we were treated. We had potatoes, meat, butter, bread, and tea for dinner, and you may be sure we had drink after in Mathew Leary’s house. They went to the store and bought two dozen bottles of small beer and a gallon of gin, otherwise whiskey, so that we were drinking until morning.

Dear friends, if you were to see old Denis Danihy, he never was in as good health and looks better than ever he did at home. And you may be sure he can have plenty of tobacco and told me to mention it to Tim Murphy. If you were to see Denis Reen when Daniel Danihy dressed him with clothes suitable for this country, you would think him to be a boss or steward, so that we have scarcely words to state to you how happy we felt at present. And as to the girls that used to be trotting on the bogs at home, to hear them talk English would be of great astonishment to you. Mary Keefe got two dresses, one from Mary Danihy and the other from Biddy Matt. One letter will do for us all,

Daniel Guiney.

However, the letters from America did not always convey the full truth of the immigrants’ situation.

On a summer’s night in 1855, Thomas McIntyre, a house-plasterer from County Tyrone, sat down in his boarding house in Boston. Weary and sore from his day’s labor, he wrote a letter to his sister back home in the village of Donemanagh.

August 27, 1855

Dear Sister,

I know today you are all, or at least a good part of you, at Donemanagh fair. I am just thinking as I sit here alone of the times I used to have on those occasions. But there are no Donemanagh fairs here. There is nothing here but work hard today and go to bed at night and rise and work harder tomorrow. Nothing but work, work away.

John wants to know if I still play the fiddle any now, but you may tell him that if he was here to put on mortar for one week, he would have very little notion about fiddling on Saturday nights. I sometimes think, when I go to my room without any one to speak to me, of the nights when we used to sit down by the fire and draw down our old fiddles. My meditations are not very pleasant. However, people need not expect a great deal of enjoyment when they come here.

Give my love to all my old neighbors and friends. You will scarce be able to make this handwriting out–I was just beginning to think that I had the trowel in my hand.

Farewell all,

T McIntyre.

Write soon.

During the late 19th century the Irish in America sent over $260 million to Ireland.

A typical Irish immigrant’s letter home was like that of Margaret McCarthy, who, in 1850, sent these lines from New York to her parents in west Cork:

September 22, 1850

My dear Father and Mother,

I remit to you in this letter twenty dollars, that is, four pounds, thinking it might be some acquisition to you until you might be clearing away from that place altogether–and the sooner the better, for believe me I could not express how great would be my joy at our seeing you all here together where you would never want or be at a loss for a good breakfast and dinner.

Your ever dear and loving child,

Margaret McCarthy

Of all the countries that sent immigrants to America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Ireland was the only one to send as many women as men. Nearly all of them were unmarried and traveling alone or in the company of sisters, cousins, or friends.

Two decades after the Famine, Alexander Sproule sent a plaintive letter to his brother in Ohio:

July 24, 1870

Dear Brother,

I have sorry news for you. On Thursday morning last, Ann, my oldest child, left here unknown to her mother and all, took all the money she could, leaving not the price of a loaf in the house, and started by steamer for Philadelphia. Perhaps you know some person in Philadelphia who could find her out. She is a smart, good girl–Whatever put this in her head? She is twenty-two years old, fair hair, clear skin, dark brown eyes, not tall. I know she is sorry for what she done. Please oblige me in a letter as we are in great trouble.

I am your affectionate brother,

A. Sproule.

Young women, especially, left their homes for the social and economic independence that emigration promised. Their letters to Ireland encouraged more of their dissatisfied sisters to follow. As one servant girl in New York City wrote to a female relation in County Wexford:

My dear cousin,

I am sorry that the priest put such a hard penance on you. You will have to come to the country where there’s love and liberty. It agrees very well with me. You would not think I have any beaux, but I have a good many. I got half a dozen now. I have become quite a Yankee, and if I was at home the boys would all be around me. I believe I have got no more to say,

From your affectionate friend, Mary Bown.

More than 150,000 men born in Ireland fought for the Union in the American Civil War of 1861-1865.

In late 1861, in a letter to his family back in County Carlow, one Irish immigrant described the war’s first great battle:

Dear Father, Brothers, and Sister,

I suppose you heard all about the fight at Bull Run, where thousands of fine fellows fell. But one thing I know you heard nothing of, which is grievous to every Irishmen, is that two Irish regiments met on that dreadful battlefield. One was the 69th of New York, a nobler set of men there was not in the world, who carried the green flag of Erin all day proudly through showers of bullets. The other Irish regiment was from Louisiana, also composed of good Irishmen who think just as much of Ireland. They opposed the 69th all day, trying to capture the poor green flag, and they took it four times but four times they had to give it up.

There were more lives lost over that flag than any one object on the field. The fourth time it was taken by the rebels, the poor 69th was so worn out that they were not able to take it back. But a man, a sergeant in the nearly all-Irish regiment, cried out that the flag of his country was going with the rebels. He leveled his rifle and shot the bearer of it dead, and then he and his company made a bayonet charge and rescued the flag and bore it back in triumph to the 69th. You may imagine the joy there was on receiving it. Surely it bore the marks of war, all tattered and torn and riddled with bullets. It will be a lasting memento to the men that bore it through that terrific day. But never before was such rivers of blood seen!

I conclude in love,

Patrick Dunny.

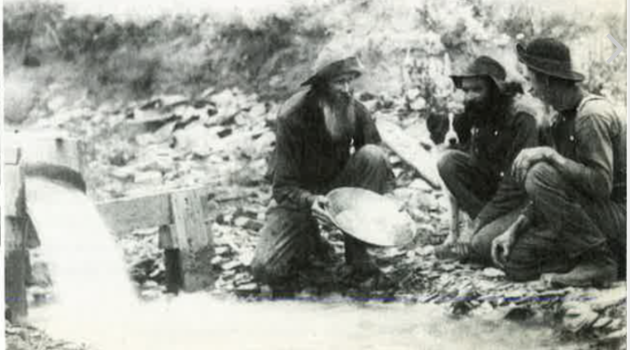

William Murphy’s first “job” in America was in the United States Navy during the Civil War. After two years service, he became an itinerant laborer.

He went to work building railroad bridges everywhere from Virginia to California.

William’s brother James died in California, inspiring him to send these melancholy reflections to his sister and her husband in Belfast.

December 13, 1880

Dear Sister and Brother,

I have to knock around so much at the work I follow that I am hardly ever more than a week or two in one place. And I make up my mind to write home every place I go. But when I get there, I think this way: “Well, I’m not going to be long here; perhaps the next place I go I can wait and get an answer.” And so it goes.

No doubt you think, why don’t I settle down like other people? I have asked myself that question a thousand times. I have gone further–I have tried to do so. But when I try it, I soon get tired and the restless spirit gets the best of me all the time. The fact is, traveling is so natural to me that I might as well try to live without eating as without wandering around. But what difference does it make? Life is but a dream, and although I know that my last days will be spent in all probability amongst strangers, I almost wish sometimes the dream was over.

Don’t think for a moment that I am despondent or downhearted. But just think for a second of the past that has gone, never to be recalled. It seems but yesterday since we were a happy and united family–mother, father, brothers, and sisters. Where are they now?

They grow together side by side,

They filled one hall with glee.

Their graves are scattered far and wide,

By mountain, stream and sea

James, the latest of our loved and lost, laid him down to rest in the far away California He like thousands more tried to find a fortune and instead he found a grave. But where could he find a more fitting resting place than in Lone Mountain? The last rays of the setting sun kiss his grave as it sinks behind the waters of the Great Pacific, and his spirit has crossed the Great Divide and joined the others in that better land beyond.

Dear sister and brother, may God bless and preserve you is the earnest prayer of your affectionate brother,

William.

When the builders of canals wanted a labor force to build the Chesapeake Canal in Virginia, they went to the local plantation owners and said, “Rent us your slaves.” But the planters replied, “No way, these slaves are worth money. Get Irishmen instead. If they die, there’s no monetary loss.”

For the Famine immigrants, especially, exploitation began as soon as they set foot on American shores. When they arrived, many Irish immigrants quickly learned that American seaports were inhabited by what they called “Yankee tricksters,” who infested the docklands and tried to rob the unwary Irish of their little capital or possessions. Those who escaped the human sharks of New York City, New Orleans, and other ports soon discovered that their new American employers and foremen were often as harsh and unsympathetic as their old landlords in Ireland.

For instance, as Patrick Walsh from County Cork later remembered:

In the years 1851-52, the Troy and Boston railroad was being made through the north-eastern part of the State of New York. The contractors and others concerned advertised liberally, promised the finest terms to the working men, in order to bring together the greatest number. They came from far distances, and without the means of returning in case of disappointment.

Accordingly, when the contractors found they had enough, and to spare, of laboring hands, they reduced the wages and kept on reducing until they brought it down to 55 cents a day. Against this rate the men went out on strike, as it would not support them, and matters began to wear a threatening aspect. At length, the legal authorities were called upon, with military force, to drive them off (which is always the custom in such cases).

I went to see the condition of those that remained, and in their “shanties,” with the fierce wind howling through them, a scene of suffering presented itself which made the heart sick. All along for miles was one continued scene of anguish and suffering, as if some peculiar curse was chasing the unfortunate people of Ireland. Yet these things were noticed as mere items of news in the papers, without any comment, as no concern was felt in their case, being Irish.

In 1855 James Dixon, an Irish seaman in Philadelphia, wrote a letter to his sister who lived in County Wexford, warning his former neighbors not to emigrate to America:

September 4, 1855

Dear Catherine,

I hope the prospects in Ireland are good this year, respecting the crops I mean. I suppose the taxes will be increased to crush the poor people yet. However, if people can live comfortably in Ireland they ought to remain there, for affairs are becoming fearful in this country. The Know-Nothings have murdered a number of Irishmen in Louisville and destroyed their property. And if feelings continue as they are, on the increase, an Irishman will not get to live in this country. Even if people are poor in Ireland, at least they will be protected from murderers.

I remain, Your affectionate brother,

James Dixon

At the height of the Know-Nothing crusade against his people, Irish immigrant Patrick Dunny wrote to his family in County Carlow:

December 30, 1856

Dear Father, Brothers, and Sister,

Its with joy I must say I received your welcome letter. In reply to your question about the election. James Buchanan is elected president on the Democratic ticket by an overwhelming majority. There never was such excitement in America before at an election, nor the Native Americans never got such a home blow before. The Irish came out victorious and claim as good right here as Americans themselves. I am happy to tell you that we are spending a very pleasant Christmas.

Your affectionate son and brother,

Patrick Dunny

In 1960 the presidential election victory of John Fitzgerald Kennedy, “Honey Fitz’s” grandson, showed that the process had finally been completed.

More than 100 years earlier, in the midst of Irish immigrant poverty and nativist prejudice, Richard O’Gorman had hopefully predicted the outcome in another letter to his friend, William Smith O’Brien:

May 17, 1857

My dear friend,

The destiny of our Race is to me utterly mysterious–for so much mental and physical vigor, elasticity and adaptability must have a destiny to fulfill. There seems to me nothing in the Irish nature to indicate a worn out, a moribund race. The moment it touches this soil, it seems to be imbued with miraculous energy for good and evil so that something Irish is prominent everywhere, and you have to praise or blame, to bless or curse it, at every turn.

My own belief is that this northern continent will fall into the hands of men whose composition will be four-fifths Celtic. The descendants of the Puritans, the Saxon element, is physically deteriorating and will soon have done its work. A softer more genial generation of men will be needed–more capable of enjoyment, more artistic than the Yankee. And our Celtic blood will just supply the want.

I am your faithful friend,

Richard O’Gorman.

The book Out of Ireland may be found in August in book stores, gift shops, or through Elliott &Clark Publishing (Washington D.C.) by calling 800-789-7733.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the July/August 1994 issue of Irish America. ♦

Leave a Reply