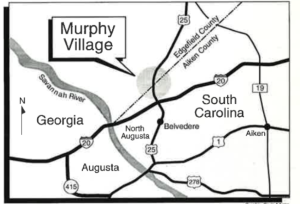

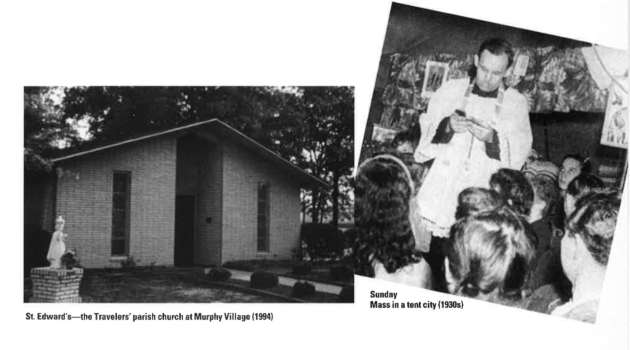

By the mid 1960s more than three hundred Irish Traveler families had settled on a fifty-acre parcel of land that they called Murphy Village. They named the site for Father Joseph Murphy, a parish priest and advocate who started the settlement for Travelers and guided it for twenty years before his transfer in 1968. What makes Murphy Village unique is that it’s a continent away from Dublin and Galway — it’s located across from an S &S Truck Stop on a stretch of U.S. 25, four miles north of the Clearwater Road on the Aiken-Edgefield county line in South Carolina.

The ancestors of these Murphy Travelers emigrated to the U.S. from all over Ireland during “the hard times.” Ancient Irish society accepted the mobility of certain social classes–poets, metalworkers, mendicants; the economic and political evictions that followed from the 17th through the 19th centuries insured Travelers a heritage of mobility. The evidence is that some may have shipped out to the States in the late-18th century but that traffic peaked in the 1845-60 period, during the Famine and post-Famine years. They arrived in Northern port cities and after the American Civil War made their way into Virginia, the Carolinas, Tennessee, Georgia, Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi. Some ventured as far west as Arkansas, Texas, and California.

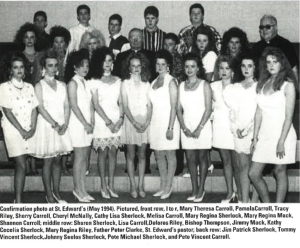

The Murphy Village Travelers are Carrolls, Costellos, Gormans, McGuires, Macks (McNamaras), McNallys, Mulhollands, O’Haras, Rileys, and Sherlocks. The Sherlocks trace their roots to the Sherlocks of Kilorglin, County Kerry, home of the celebrated Puck Fair.

The ten surnames haven’t changed much, and because they’re shared among so many families–there are literally dozens of Eddie Carrolls, John Sherlocks, and Pat O’Haras–the villagers, like their Irish counterparts, have concocted an array of by-names or nicknames to distinguish one family from another. “Bunk,” “Sudel,” “Slick,” “Cisco,” “T.O.,” “High Pockets,” “Jabber,” “Sweeney,” “the Sheriff,” “Big Shot,” “Little Shot,” “Rock,” “Tommy Taylor,” and “Tommy Daily” are current in Murphy.

Practiced storytellers, the Murphy Travelers offer intriguing oral histories that begin their American odyssey with “Old Man” Tom Carroll, who is said to have debarked in New York City and teamed up for a time with a Jewish cloth merchant before selling out to go horse trading from Maine to Ohio. When “Old Man” Carroll sent passage money home to bring his family out, he brought his friend Peter Sherlock as well. Sherlock is credited with trading horses from New York as far south as Murfreesboro, Tennessee. “Old Man” Tom Carroll is reputed to have outlived three wives and fathered twenty-five children.

Pat O’Hara, a Traveler in the Irish North, once took it upon himself to mend a boiler in Belfast that exploded like an H-bomb. He fled the country rather than face the consequences. O’Hara is said to have hooked up with the ubiquitous Tom Carroll in Washington, D.C., where he struck a partnership in the mule trade with him. Another, Bryan O’Gorman, set up a tinshop next to a livery stable in Philadelphia and soon found himself trading horses through Tennessee, Georgia, and Florida.

Then there was the dapper, articulate “Uncle” Matt Sherlock, who lived into his eighties and who commanded respect in and out of the Traveler community. He is described in 1941, striding through an encampment of 200 tents in tweed riding coat and breeches, brandishing a knotted walking stick and checking the stock like an educated Irish country squire. These Traveler histories, true or apocryphal, are the familiar origin legends of the Irish-American experience.

Certainly the Travelers did move south in numbers during the Reconstruction Era. And certainly they traded horses and mules and established head-quarters around the principal stockyard-cities. For about a century they gathered on April 28 in Atlanta and May 28 in Nashville and during other seasonal holidays–Easter, Christmas, Fourth of July, and later during World Series week–in the campsites of Georgia, Tennessee, and Mississippi to replenish their stock, form new partnerships, and exchange news of the road. They used the holidays as a time of spiritual renewal, celebrating marriages and births and burying their dead.

From all corners of the Southeast, Atlanta-based Travelers shipped the remains of their dead back to the Paterson Funeral Home on Peachtree Street near the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception. From April 26 to 28 each year, they converged on the city for a gathering of the clan and a grand funeral. Vintage Atlantans remember them massing by the hundreds at a solemn requiem honoring a few to a dozen and, with a cortege of as many hearses and scores of carriages, proceeding to West View Cemetery, keening and lamenting their dead.

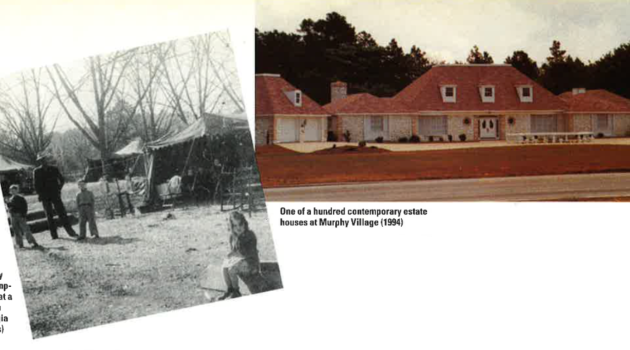

Typically, small bands of three to five families numbering 40 to 50 people gravitated south in ornate horse-drawn wagons with commodious tents and living paraphernalia–four-poster mahogany beds to fine china. They moved south, where the climate was kinder, more conducive to a life on the road; south, where there was a ready economic niche among a country people dependent on peddlers and traders in mules and horses. In spite of their relocation to the New World, the pattern of the Travelers’ day-to-day lives in the American South was not significantly different from that of their lives on the roads of Ireland.

In the late 1860s they established the first seasonal circuits, working as jacks-of-all-trades: farm laborers, chimney sweeps, and hawkers of sundries. While men labored and traded and mended kettles, milk-pails, lanterns, and tubs; women bartered baskets, beads, lace, pins and needles, rings and jewelry for smoked hams, chickens, eggs, and jellies with wives living in hamlets and towns and on rural farmsteads. But their experiences in the Old Country had also taught them about muleflesh and horseflesh, and it wasn’t long before they acquired a stake and fixed on trading live-stock as their principal occupation.

Though they came to specialize in mules, by the turn of the century they were known through the American Southeast as “the Irish Horse Traders.” They scorned “tinker” and “gypsy” as terms of opprobrium; they were sometimes called “the Georgia Travelers” because of their base in Atlanta, but they preferred “Irish Travelers”–they were, after all, descended from the Traveler families of Ireland.

They resisted assimilation into the ethnic community and into the larger Southern community. They were Irish and Catholic and, more than mainstream Irish Americans, they were determined to preserve their culture and religious traditions intact. To this day they live apart from the settled community and pass on a pattern of Irish life that has virtually disappeared even from the Irish scene. One Traveler put it this way: “We keep to the road. There’s no better life for a man.” In a way the Murphy Travelers are more Irish than the Irish themselves and the most Irish of Irish ethnics.

In the South their way of life went unchanged for three generations until, in 1927, the Georgia State Legislature levied a burdensome tax on itinerant traders that forced many Travelers to other employments. They sold their mules and brightly decorated top-wagons and replaced them with automobiles and pickups with trailers. They invested in painting equipment and floor covering and went back on the road contracting spray-paint jobs and selling and laying linoleum.

To avoid the crippling taxes, the holdouts among them rented barns or entered partnerships with local horse and mule traders, but by 1954 tractors and farm mechanization had taken over; the market in horses and mules had collapsed completely.

They are still itinerants–men still take to the roads in cars and trucks to work in the painting and rug trades, in roofing and asphalting, in tool and hydrauliclift sales. They still roam upcountry into Iowa, Illinois, and Michigan and further afield for weeks and months at a time. Whole families still shift north in caravans to apartments, motels and boarding houses during the long hot summers.

Customs surrounding Traveler life–the dowries and courtship rituals, intermarriages and arranged marriages, runaways, fosterage, and funerals–follow traditional 19th-century Irish country ways. And, though they speak now in a brogue-tinged drawl and listen to country music, the Murphy villagers have carried over some few words of Shelta, a kind of Irish Traveler code-language that they call “the cant.”

The Traveler women still marry earlier than “the country people,” a term they use for non-Travelers, and parents are still vigilant with eligible sons and daughters in their effort to arrange a successful match. Nowadays courting centers on dances and films and television and on “looping” and “cruising,” local variations of “strutting one’s stuff.” Young women marry as early as fourteen, young men as early as eighteen. As part of marriages arranged by parents, a dowry in money and goods usually changes hands and puts newlyweds on a firm footing.

Among Travelers there is apparently a greater taboo against marrying out of the community than marrying kin. Marriages of first and second cousins are arranged because it’s thought that “it’s good to keep the blood in the family.” Arrangements can, however, be sidestepped by mutual consent or by an elopement (a runaway)–where a young couple hies off to spend a night together. Runaways, in recent years less frequent, are often sanctioned by family and even orchestrated by concerned mothers.

Though most Traveler children leave local parochial and public schools between sixth and eighth grades, they leave more literate, more independent, and more conscious of heritage than their “country” classmates who stay on. Some have gone on to secondary education at North Augusta, a few have gone to college. But as one Traveler put it, “They have ambitions to be their own boss–traveling and selling is an exciting life.”

Young women have vocations as wives, mothers, and homemakers and seldom look for work outside Murphy Village, though a few in recent years have taken jobs in offices and schools. Betty Jo Costello, the secretary at Our Lady of Peace in North Augusta, has won honors and awards and served full terms on both Edgefield County and the OLP school boards. Traveler society remains matriarchal. Because men are absentees, women pay the bills and manage the finances. They give direction to Traveler life and set high moral standards.

Ignorant outsiders, wary of a perhaps too-Catholic influence or what they regard as a flamboyant “gypsy” lifestyle, have exaggerated cultural differences and stereotyped the Irish Traveler as idolatrous, lascivious, irresponsible, violent, dirty, dishonest, and alcoholic. The Travelers are none of these.

They are a vast extended family with strong religious values, a fiercely independent clan that insists on its right to privacy and looks after its own. The Murphy Travelers boast an incredibly low crime rate and virtually no recorded violent crime–no rapes, no robberies, no drugs, no alcohol abuse. Divorce is rare and juvenile delinquency nonexistent. They provide for their elderly and have no history of welfare.

In recent years investigations of business fraud, tax evasion, gambling, and truancy have led to prosecutions and arrests of scammers and schemers by authorities. As one Traveler put it, “There are villains among any honest people, and we’re no exception.” They are saddened by adverse publicity that is often generalized to the whole community, and by whispered reports of allegiances to Old Country ways–to “gypsy” kings and queens, common marriages, spells against evil spirits, idol worship–that probably say more about the detractors than the Travelers themselves.

Even the Catholic Church, the backbone of the community, has occasionally wavered in its support. Instead of recognizing the Irish Travelers as a distinct subculture, a special apostolate with special needs, well-intentioned bishops and priests have, over the years, pressured them to conform and modify long-standing customs and beliefs that have nurtured their faith for centuries. Fortunately a few enlightened priests have provided pastoral balance.

The growing community of Travelers in Murphy Village–estimated now at 2,400–has dramatically bettered themselves and established a strong political-economic base in Aiken and Edgefield counties. The Political Committee, which commands a bloc of a thousand or more votes, is wooed by politicians and business leaders who heed them because of an influence in local affairs. They contribute to political campaigns, broaden the tax base, and invest in the local economy.

When the Travelers started their circuits into western South Carolina from Georgia in the 1930s, they never realized they had come to stay. As they occupied the sites that became Murphy Village, they gradually surrendered their tents for small trailers and then for double-wides. Since the 1970s, they have, however, “dug in” and extended their holdings. They have built lavish stone, brick and filigreed homes on oversize lots with garden shrines and grottos honoring the Virgin and patron saints.

In spite of a reticence to attract attention from outsiders, they display Elvis-like ostentation in their choice of homes, furnishings, cars, and fashions. “We’re foreground people. What we have we put on display for everyone to see. We don’t save much for the background,” one Traveler woman explained. They call the new estates, located across U.S. 25 and adjacent to the original site and St. Edward’s Church, Kerry Village and Heatherwood and the streets in them Waterford, Kildare, and the like.

The Irish Travelers of Aiken and Edgefield know the Ewan MacColl song that says, “Winds of change are blowing/Old ways are going,” but they don’t believe “travelling days will soon be over.” They have adapted but not abandoned the nomadic life. “It was,” according to a village elder, “one of the happiest lives on earth.”

Gabriel Byrne’s 1994 film Into the West offers an engaging fantasy based on a mixture of myth and reality. The film telescopes Irish Traveler life in Ireland and, in the final scene, eloquently sums up the Traveler experience. Reflecting on the hostility of the Big World and on the sameness of human nature, “Papa” Reilly tells his children, “There’s a bit of the Traveler in everybody. Very few of us know where we’re going.” The Murphy Village Travelers, as inheritors of that tradition, seem to know better than most.

Author’s Notes: Murphy village was entirely in Aiken County at its founding. With the realignment of the county line in 1967, the settlement was divided between Aiken and Edgefield counties. Out of respect for Travelers’ wishes, quotations are attributed generally rather than to individuals.

Daniel J. Casey, Dean of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences, Berry College in Mount Berry, Georgia, has published more than 120 books, monographs, articles, and reviews on Irish and Irish-American subjects, as well as fiction and poetry.

Conor Casey, a freelance writer, has covered prominent figures on the American sports scene.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the September/October 1994 issue of Irish America. ♦

Leave a Reply