The trails of death and the circles of giving. The Irish and Native American connection.

Trails of Tears and Circles of Giving

“I know the cause of humanity is one the world over,” wrote fugitive slave Frederick Douglass at the beginning of 1846, at the conclusion of his “transformative” four-month stay in Ireland. At that stage, neither he, nor the people who had hosted him, were aware that Ireland was on the cusp of a devastating famine, which would prove to be one of the most lethal famines in modern history.

During the space of six years, Ireland lost one quarter of her population. Amidst the unrelenting onslaught of eviction and exile, of disease, dislocation and death, a few glimmers of humanity were evident. In 1847 – remembered as “Black ’47”– an unprecedented wave of sympathy and charity got underway on behalf of the Irish poor. Donations came from all parts of the world –from India to South America, from China to New Zealand, from Russia to South Africa, and everywhere in between. Heads of state including President Polk, Queen Victoria and Sultan Abdulmecid, also donated.

More impressively, donations came from groups of people who were themselves poor, marginalized and despised. This included a donation from inmates on a prison ship in London, who sent 17 shillings made up of pennies, and who were all dead a year later from prison fever; money was sent from formerly enslaved people in the Caribbean who gave from their hard-earned wages; and contributions came from Native Americans, whose rich lands had been taken from them and they and their culture labeled as savage. Despite their poverty, these people all gave from their own meagre resources to help the starving in Ireland.

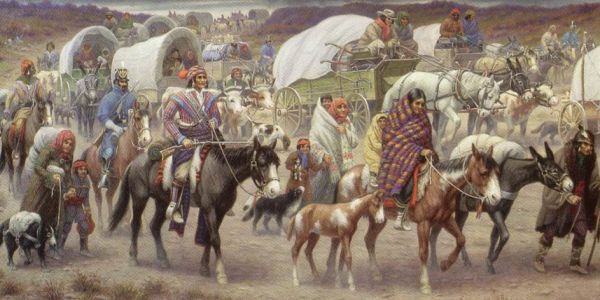

Native American donations included several from the Choctaw and Cherokee Nations, who historically were natives of the rich Mississippi farmlands in the south east of America. That had been their home until the ‘Indian Removal’ of the 1830s, which systematically displaced five Nations – around 60,000 people – took their ancestral lands and moved them to the arid lands of eastern Oklahoma (then known as Indian Territory). It was a journey of over 5,000 miles, through nine different states. The removal severed a connection with a land and a sense of place that was thousands of years old; while the journey, known as the Trail of Tears, resulted in hunger, privation and thousands of deaths. A decade after this displacement, as Irish people were undertaking their own trail of tears across the Atlantic on the infamous coffin ships, a number of Native American Nations sent their generous donations to Ireland thus demonstrating, as Douglass had claimed, that “the cause of humanity is one the world over.”

In October 1847, the London Times – no friend to the Irish poor – published an article mocking the fact that Ireland had received so many charitable donations in the preceding months, describing the country as a ‘begging box’. Listing some of the donors, they stated that a dozen “Red Indian tribes” had given. This article, offensive as it was, offers a rare and tantalizing glimpse into the extent of Native American generosity. Sadly, unlike the rich and famous who gave, the contemporary records do not always list donations from the poorer members of society who contributed or name them individually. Fortunately, the donations of the Choctaw and Cherokee Nations were documented at the time and they tell an incredible story.

Within months of the second and devastating failure of the potato crop in 1846, news traveled around the world that hunger and disease were taking the lives thousands of poor people in Ireland. This information created a spontaneous and global movement to send aid to Ireland. It was frequently accompanied by the recognition that the powerful British government was doing little to help its neighbor and fellow member of the United Kingdom. By the beginning of 1847, committees had been established throughout the world to raise money for Ireland. By April, news had reached the south central region of America where many Native Americans had settled. Hearing of the Irish suffering prompted an immediate response from the Choctaw people residing near Fort Smith in Arkansas. In April, they sent $10 to a relief committee in New York, who then forwarded it to the Society of Friends in Dublin. As this money was making its way across the Atlantic, the Choctaws were already making a second and larger collection – the $170 donation which is currently attracting so much attention. Again, it was sent to the committee in New York and, from there, onwards to Ireland. Today, this second donation would be worth over $5,000.

The actions of the Choctaws inspired the Chief of the Cherokees, Coowescoowe, to convene a meeting suggesting that they make a collection both for Ireland and for the poor in the Highlands of Scotland, where the potato crop had failed. Coowescoowe, who was also known as Chief John Ross because of his mixed Scottish heritage, had been a fierce opponent of the Indian Removal, and his wife had died during the Trail of Tears. Following this meeting, the Cherokees sent two donations of $103 and $245. Their money was channeled through the relief committee in Philadelphia. It is possible that additional sums of money were raised but other Nations but that they were not documented or have not yet been located.

The donations by the Choctaws and Cherokees did attract attention at the time, unfortunately often through a racialized prism. The Arkansas Intelligencer opined:

What an agreeable reflection it must give to the Christian and the philanthropist to witness this evidence of civilization and Christian spirit existing among our red neighbors. They are paying the Christian world a consideration for bringing them out from benighted ignorance and heathen barbarism. Not only by contributing a few dollars, but by affording evidence that the labours of the Christian missionary have not been in vain.

Just as offensively, the Chairman of the Philadelphia relief committee informed Chief Coowescoowe that:

How sensibly we are affected by this act of true Christian benevolence on the part of the Cherokee nation. Especially are we gratified by the evidence it affords of your people having already attained to higher and purer species of civilization derived only from the influence of our holy religion by which we are taught to view the sufferings of our fellow being wherever they exist as our own.

In June, the donation by the Choctaws was being reported in Irish newspapers, many simply noting, “the Choctaw tribe of north American Indians have contributed a sum of $170 dollars for the relief of the distressed Irish.” One Cork newspaper, however, reported that the Choctaws had contributed $269, adding, “Lo! The Poor Indian – he stretches his red hand in honest kindness to his poor Celtic brother across the sea.” In a separate article, the same paper lamented on “The Irish Exodus” and the inevitable depopulation of Ireland. It warned that the emigrants who survived were being sent to the backwoods of America to replace the Native Americans, who had been “extirpated by the fire-arms and fire-water of most Christian England.”

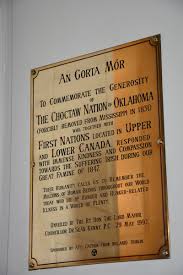

While the role of the Cherokee Nation during the Great Hunger has been largely forgotten, the donation from the Choctaw Nation has been remembered and honored in Ireland for the extraordinary gesture that it was. In the early 1990s, as Ireland was gearing up to commemorate the sesquicentenary of the Great Hunger, Don Mullan of AFRI, a life-long activist for social justice, made the story of the Choctaw donation more widely available. At the same time, he comparing the suffering of the Irish people in the 1840s to those experiencing famines in the 1990s, most notably in Somalia. His work led to a plaque being unveiled in the Lord Mayor’s Mansion House in Dublin in 1992. The location was particularly appropriate because during the Great Hunger and the forgotten famines of 1822, 1831, 1862 and 1880, the Mansion House had been at the center of fund-raising initiatives to help the starving poor.

The donations had been remembered at the highest political level. Irish Presidents, Mary Robinson and Michael D. Higgins, have expressed their gratitude on behalf of the Irish people to representatives of the Choctaw Nation. In turn, in 1995, President Robinson was made an honorary Choctaw Chief – the first woman to be so honored. In March 2017, An Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar, when visiting the Choctaw Nation announced that a scholarship had been created for Choctaw students to study in Ireland.

Trail of Death by Kieran Tuohy an Irish Sculptor who works in bog oak.

The donation has also been commemorated in art. In 2005, Quinnipiac University purchased Galway-based sculptor, Kieran Tuohy’s, beautiful carving in Irish bog oak, Thank you to the Choctaw. Tuohy has also created the haunting, Trail of Death. In June 2017, the small town of Midleton in east Cork unveiling a six-metre tall circle of feathers, called Kindred Spirits. Clearly, the kindness of these strangers in Oklahoma and Arkansas, who had no connection with Ireland and who were themselves despised and impoverished, has not been forgotten by the people of Ireland. In 2020, however, this memory has taken a more practical turn as hundreds, possibly thousands of people of Irish descent have been donating to Native Americans who are disproportionately affected by the coronavirus. Their vulnerability arises from decades of social and economic marginalization and poverty, which was consolidated by the Trail of Tears.

The on-going connection between Native Americans and the Irish represents more than simply the giving of financial aid. In the Choctaw language, there is a small word, ima, that has no precise translation. It roughly means “to give,” but it also represents a wider sense of how to live and how to interact with those who need help. Despite repeated and brutal attempts to wipe out both Irish and Native American culture, both have survived, although not without much suffering. The circle of giving between Native Americans and the Irish people is a reminder that the winners don’t always get to write the history and that humanity will triumph. ♦

Christine Kinealy’s last book Black Abolitionists in Ireland was published in 2020 by Routledge. It examines ten abolitionists – nine men and one woman –who visited Ireland between 1791 and 1860. Kinealy is currently working on Black Abolitionists in Ireland (vol. 2)

Christine Kinealy’s last book Black Abolitionists in Ireland was published in 2020 by Routledge. It examines ten abolitionists – nine men and one woman –who visited Ireland between 1791 and 1860. Kinealy is currently working on Black Abolitionists in Ireland (vol. 2)

Christine is the Director of Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute at Quinnipiac University, and is the author of many books and articles on famines in Ireland.

Thank you so much for this wonderful article and for sharing the research behind it. Very much appreciated. Jenn

Thank you for sharing this beautiful article with all of us.

In an era of Full Greed Ahead, it is really inspiring to learn about

the shared spirit of Celtic and Native American cultures.

Both remain a blessing to us all, and the poetry, prose , story telling and HUMANITY of Irish life and Indian life have not succumbed to endless

oppression and never will

this story should be in every school in the country, the same way that the great Dwamish leader Chief Seattle’s speech was for many years.

The music, dance,storytelling and humanity of Celtic and Native American cultures all reflect a spirit and nobility that transcends politics, and will never die!

Slainte!!!

David Amram

Thank you for sharing beautiful and informative article with all of us who are lucky enough to read it

This should be in every school in the country, the way Chief Seattle’s speech was for so many years. !

The spirit of Celtic culture is sill alive and so is spirit of all the Native nations of this continent, whose people greeted the first visitors who came here by boats.

In an era of Full Greed Ahead, this story is more meaningful than ever

Slainte

David Amram