By Tim McGrath

Getting a memorial to Commodore John Barry at the U.S. Naval Academy took the patient determination of organizations, a talented sculptor, an Irish marathoner, and countless well-wishers – and the leadership of two great friends.

Years ago, a writer lecturing to college students was asked what made for a good Irish story. After a long pause, he told the class such a tale required a legend, a couple of heroes, long odds to overcome, and, finally, a bittersweet victory.

The story of the gate and memorial honoring John Barry at the United States Naval Academy has all this – and more.

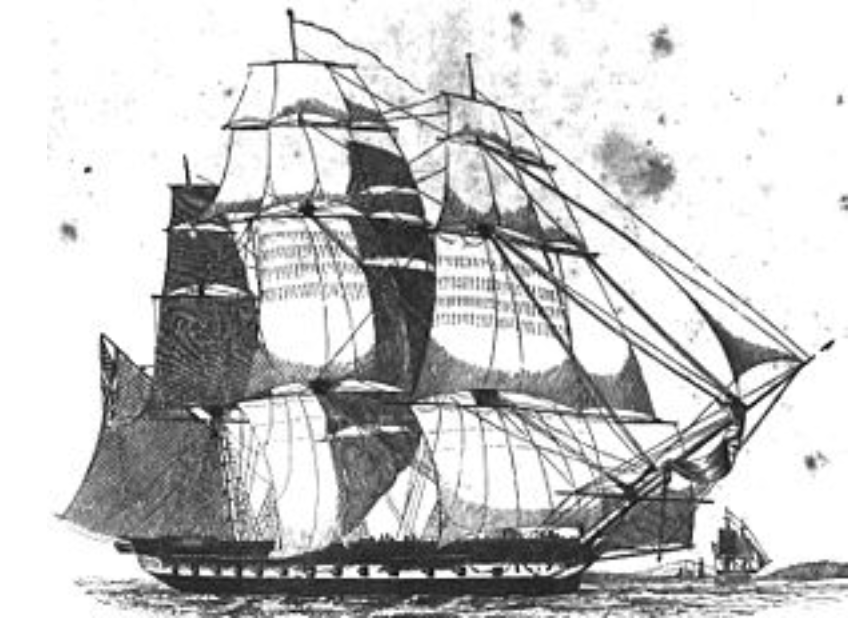

To begin at the beginning, there’s the legend: John Barry, a refugee from the Draconian Penal Laws of the eighteenth century, whose parents sent him to sea as a boy under the watchful eye of his mariner uncle. John was a teenager when he came to Philadelphia around 1760, where he began his meteoric ascent up the ratlines of the maritime trade, becoming a ship’s captain at twenty-one years of age. At the outbreak of the American Revolution he commanded the finest ship yet built in the colonies, the Black Prince, working for the richest man in Philadelphia, Robert Morris. The Revolution brought out the warrior in the man. After eight years of battle at sea (and on land) he was the last captain of the Continental Navy employed by Congress. In 1787 he embarked on one of the first trading voyages to China from the United States.

Barry “swallowed the anchor” upon his return, only to be asked in 1794 by his friend, President George Washington, to help create the United States Navy, becoming its first commissioned officer. Over the next seven years he oversaw construction of the first frigates, wrote the navy’s first signal book, fought in the Quasi-War with France, and trained the next generation of naval officers, many of them on their way to distinguished careers when Barry died in 1803.

The debate over Barry’s being “the Father of the American Navy” began shortly after his death. And, while others such as his friend John Paul Jones and his Commanders-in-Chief, George Washington and John Adams all have their advocates for the title, none possess the enduring support Barry’s had, thanks to Irish-Americans who have passed their belief down to succeeding generations as part of their heritage.

No two men were more certain of this belief than Marylanders Jack O’Brien and John McInerney, near legends themselves in the Irish-American community for their service in Irish organizations and causes. In the 1990s they helped lead the drive to honor the Irish Brigade of the Civil War with a monument at Antietam Battlefield, an emotionally moving work created by sculptor Ron Tunison and Codori Memorials. With the new century, Jack and John turned their attention to Commodore Barry – and the United States Naval Academy.

Armed with the latest congressional resolution from 2005 declaring Barry “first flag officer of the United States Navy,” Jack and John asked local divisions of the Ancient Order of Hibernians for their sponsorship. Once given, they made their first overture to Academy officials in 2007, and given detailed instructions for “Memorials and Commemorative Works.” To create the memorial, they again turned Codori Memorials and Ron Tunison, who began sketching out ideas. It looked to be smooth sailing.

It was not. In 2009, Jack and John were informed by the Academy Superintendent that a Barry memorial “would not be appropriate” for placement at the Academy. Instead, they were referred to other sites.

Others might have taken this directive and acted on it, and the Barry Memorial might have found itself at another location. But Jack and John were not deterred (one mutual acquaintance once said that had they been given the task of getting astronauts to Mars, there’d be a space station there by now). After filing an appeal with the Academy, they enlisted a host of other Irish-American officials, veterans, and politicians in an all-out effort to have the navy brass see the worthiness of honoring such a distinguished forebear.

The AOH and Friendly Sons of St. Patrick chapters across the country made the Barry memorial part of their meeting’s “New Business.” Other Irish-American notables including Seamus Boyle, Keith Carney, and Russ Wylie did their utmost to fuel the fire. Soon they had some impressive allies, including past Secretary of the Navy John Lehman and Military Archdiocese Archbishop Timothy Broglio, both questioning not the need for such a tribute, but why there wasn’t one in the first place. Ralph Day, an AOH presence for years and a navy vet himself, added some zest to the efforts by appearing at functions as John Barry, wearing a replica of the commodore’s uniform with distinguished aplomb.

In May, 2010, a delegation of Irish-Americans met with a subcommittee of academy officials to present their case. Two months later, they received the subcommittee’s answer: another rejection. Again, the officials believed the matter laid to rest. Again, Jack and John appealed. They also concentrated on a letter-writing campaign, urging supporters to send letters to Academy officials as well as to their congressmen and senators. A good many retired admirals joined in. That August, the Academy reached out to Jack and John: there was to be a new pedestrian gate on Prince George Street; would naming it the “Barry Gate” and setting a memorial alongside it suffice?

It certainly did. A series of meetings were held to develop the design of the memorial with Sara Phillips, Executive Director of Academy Projects. With the assistance of Commander Dave Church, USN (Ret.), plans were approved. Now all Jack and John had to do was come up with the cost: over $200,000. Using the slogan, “Let’s Meet at the Barry Gate,” the campaign began in earnest.

Over the next three years contributions came in from all parts of the country. The Gate was dedicated at a small ceremony on January 6, 2012. By then it was becoming clear that to reach the financial goal, the campaign needed a new twist – a benefactor, an idea – something.

Enter Tom McGrath. His story, like Barry’s, is that of an Irishman finding success in America. Born in Fermanagh, Tom is that most rabid of athletes, an ultra-marathoner, who happily takes to the road for charitable causes. He owns the Black Sheep Pub in Manhattan, known for its Irish food and spirits, but thanks to his running, he looks like the last man on earth to earn a living selling Guinness or bangers and mash. It was no surprise to those who know him that he volunteered to run the 250 miles between Manhattan and Annapolis during an oppressive heat wave in July, 2012. Calling it “the hardest running of my life,” Tom averaged over thirty miles in eight straight days. Soon afterwards the campaign went over the top, and a date was set for dedication: May 10, 2014.

Meanwhile, Ron Tunison was working on the bas relief of the commodore. Using Gilbert Stuart’s portrait as a reference, Ron painstakingly took the memorial from its original sketches to true-to-life reality. Sadly, he died shortly after its completion, on October 19, 2013.

The bitter winter of 2014 brought work stoppages up and down the east coast, but Jack and John unstintingly completed the final touches and resolved last minute hassles before May 10. In all these years, they rarely lost hope nor temper, both maintaining the same calm demeanor Barry himself was noted for on the quarterdeck. By mid-April everything looked to be finished.

Sadly, fate wasn’t finished. On May 7, John McInerney died in his sleep. His passing added an unfathomable sadness to the coming festivities.

The skies were foreboding on Saturday, May 10, when hundreds arrived at St. Mary’s in Annapolis for mass. From there they proceeded to Prince George Street and through the Barry Gate. The crowd ranged from Kevin Conmy of the Irish Embassy to Mary Nolan, President of the Commodore Barry Club in Brooklyn, who’s organized an annual pilgrimage to Philadelphia each Memorial Day for a commemorative mass and visit to Barry’s gravesite. Ron Tunison’s widow, Alice, came with her family, as did John’s widow, Louise Verret. An empty chair with John’s picture bore witness as well.

Intermittent peeks of sunlight came through the darkening clouds. The ceremony was a fitting tribute to John Barry, dignified without pomposity, humorous at times, and understated throughout. The first meeting at the Barry Gate went without a hitch. The rain waited until everyone reached Dahlgren Hall for a sumptuous lunch. Throughout the gala, Louise graciously accepted condolences with Jack O’Brien frequently by her side, friend and stranger all wishing her husband could have been there.

Knowing John McInerney he was busy, keeping the weather gods at bay.

Tim McGrath is a recipient of the Samuel Eliot Morison Award for Naval Literature and a two-time winner of the Commodore John Barry Award. His latest book is James Monroe: A Life. He lives outside Philadelphia.

Tim McGrath is a recipient of the Samuel Eliot Morison Award for Naval Literature and a two-time winner of the Commodore John Barry Award. His latest book is James Monroe: A Life. He lives outside Philadelphia.

I had a cousin, “McCready” who was a rear admiral in WW2.

I do not remember his first name.

Do you have any information on him?

Joan

Commodore Barry, Everyone should know his name and story. One of the hero’s of the American Revolution and the Father of the American Navy

Thank You AOH and everyone who work so hard so many years to get Barry’s Gate approved.

So why was John Paul Jones deemed the Father of the american Navy. Jones was essentially a brigand who raided towns in Scotland and retired to the continent? Can anyone elucidate on this issue?